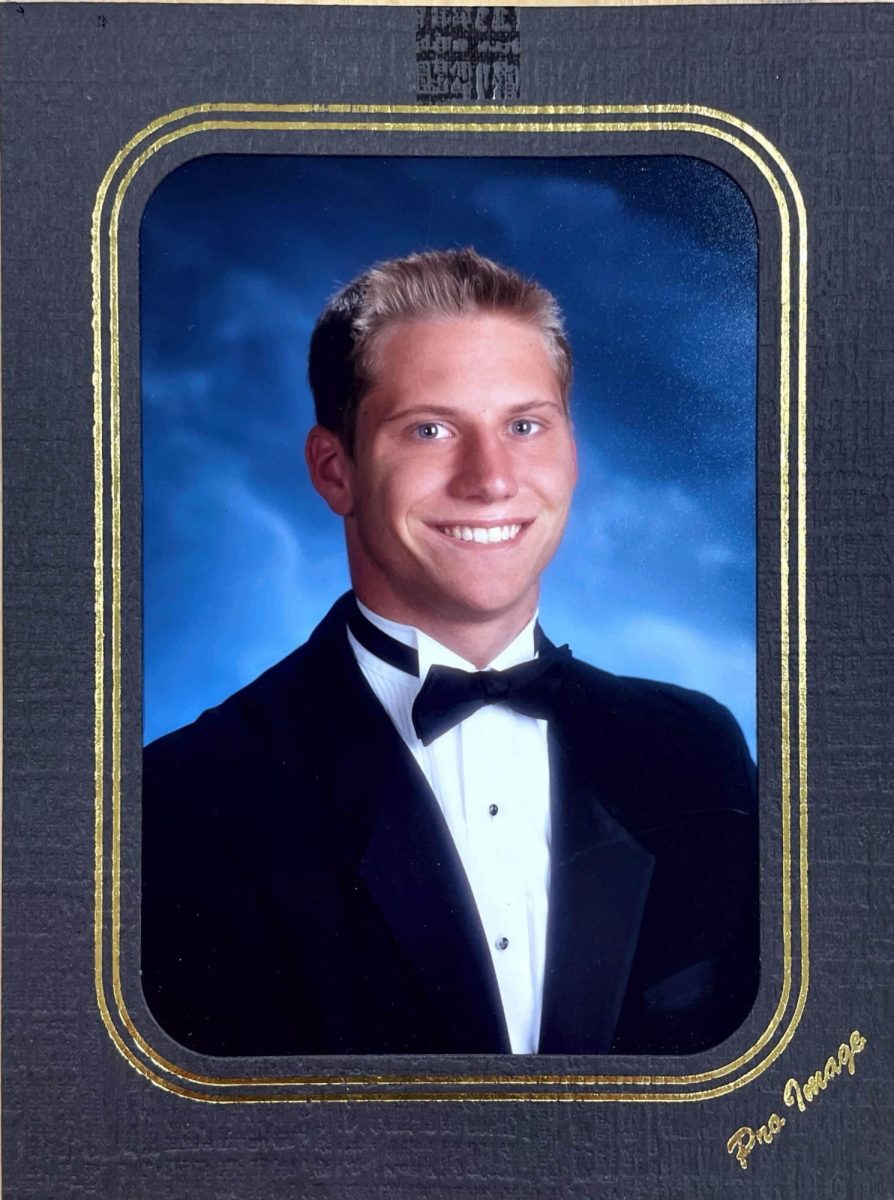

By the end of his senior year at Saratoga High in 2005, Dan Wallace was named the Most Valuable Player in four different sports: football, basketball, volleyball and track — a remarkable achievement fit into just three seasons.

In basketball, Wallace holds the all-time career rebounding record, is seventh in most points scored and is the leader in steals. While he never played sports in college, he graduated as one of the school’s all-time top athletes.

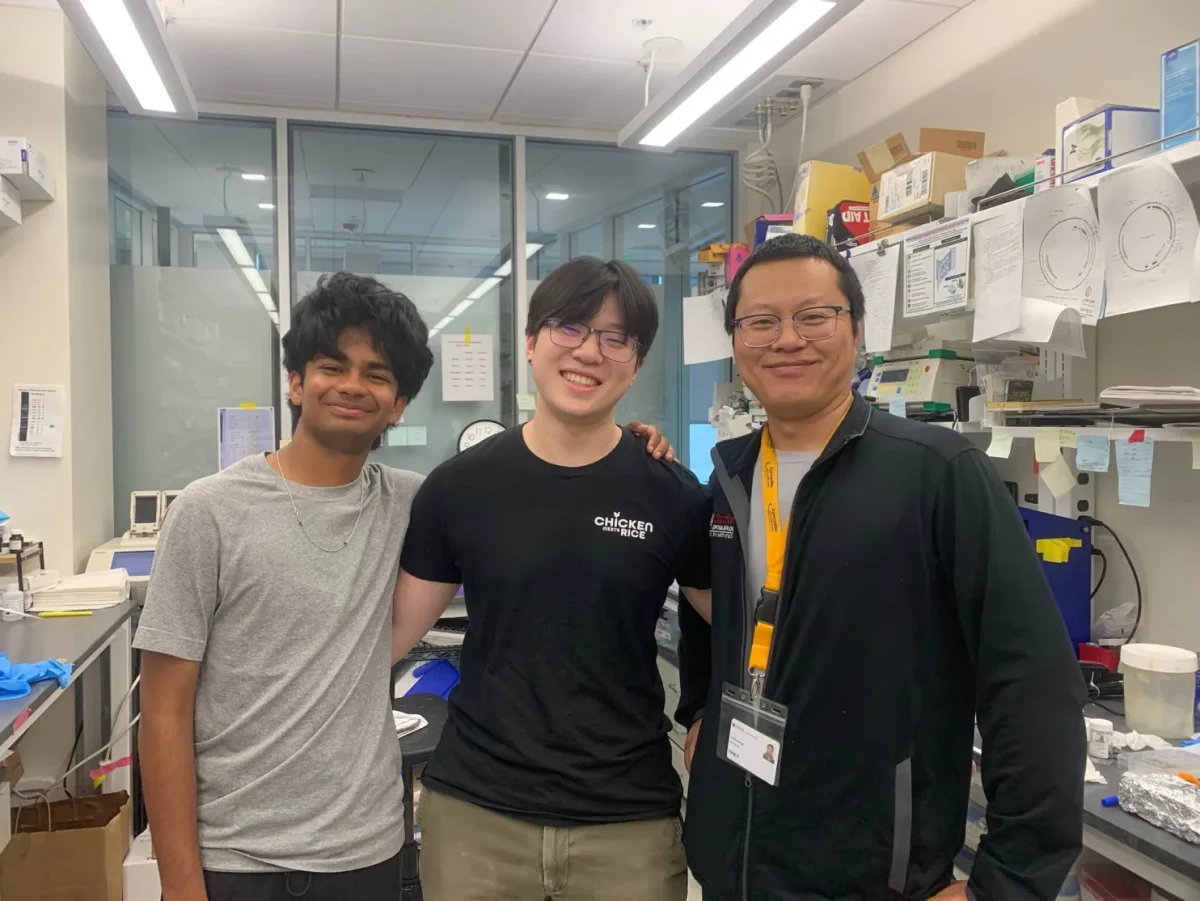

The 2004-2005 varsity basketball team roster, featuring senior Dan Wallace.

But even as he gained praise from teachers, coaches and friends for his athletic accomplishments, few knew he had struggled for years inside the classroom because of a hidden disability that began when he was a toddler.

As a 2-year-old, Wallace was rushed to the hospital with febrile seizure and a 108.7 degree fever. He survived, but suffered minor brain damage on the right side.

Until age 4, he couldn’t speak or hear very well.

At 5, he was enrolled in a preschool when the first of several traumatic events occurred because of his disability: He recalls being hit by a frustrated, angry teacher. That same teacher told his parents he was mentally challenged and should instead be placed in a bus that took students to an education program dedicated to children with disabilities — a bus that other preschool children made fun of.

At age 6, his placement in this special program was reversed, and he was sent to his local elementary school in Saratoga: Foothill, where he remembers experiencing ridicule, even being targeted with pejoratives like “retarded” from his classmates. One teacher even told him that he was a waste of their time and that he would never be able to “do academics right.”

In 2011, six years after graduating, Wallace returned to SHS and took a position as a special education teacher, determined to help kids who have learning disabilities and need help and understanding on their academic path.

Although he wasn’t diagnosed early in childhood, Wallace later learned he had dyslexia — an incurable disorder that affects reading and spelling. The condition did not affect his intelligence, but it gave him difficulty understanding written words and sentences. The condition made school work a lot harder for him to complete than other students.

As he would come to learn, dyslexia does not doom those who have it to academic or professional failure. In fact, according to researchers at the University of Cambridge, people with dyslexia often have “enhanced abilities” when it comes to areas such as discovery, invention and creativity.

This study is supported by the many stories about successful figures with dyslexia, such as Charles Schwab. Although Schwab was diagnosed with dyslexia, Schwab was regarded as an out-of-the-box thinker. According to The Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, Schwab was one of the first to come up with the idea of opening the stock market to everyone, when he set up his own brokerage office. His company went on to become the largest publicly traded brokerage business, with $7.5 trillion in assets according to CNBC, and to revolutionize the financial industry in its time.

Although Schwab founded his company in 1971, his condition wasn’t discovered until the 1980s when his son was also diagnosed with dyslexia; He was 58 at the time. His condition is commonly referred to as “hidden disability” because of how it was masked by his success.

Wallace mirrored the idea that people with dyslexia can go on later in life to still accomplish great things.

His own experience is one of the main reasons Wallace became a special education teacher. The Individualized Education Program (IEP), headed by Brian Elliot, provides support for children with learning disabilities that he felt he needed more of when he was a student.

Over the years, he has also coached several sports teams at the school, including track and field jump events, basketball, volleyball, football and lacrosse.

Wallace grappled with early 2000s conventional schooling techniques

In his preschool and early elementary school years, Wallace suffered mistreatment and a lack of teacher support. Before the mid-’90s, he said many teachers were neither trained to work with students with disabilities, nor were there effective specialized programs providing a comparably adequate education. Because of this, they categorized his disability as falling under the umbrella of general mental retardation and sent him away from the standard public elementary schools to a program developed generally for children with disabilities.

The 1975 Education for all Handicapped Children Act (EHA), renamed in 1990 as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), was signed into law by President Gerald Ford.

The law opened public schools to children with disabilities and guaranteed them a “free and appropriate public education,” known as FAPE. This act laid the foundation to ensure students received the proper opportunities. In 1994, the IDEA act built on FAPE and required that students with disabilities be educated in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). FAPE and LRE were the most impactful acts for Wallace.

The IDEA act also later defined categories of disabilities in which schools can identify where each student falls and what treatment they need. Soon after the 1994 changes, Wallace was diagnosed with dyslexia in kindergarten, allowing him to return to the public school system.

“Imagine living here in Saratoga, but a little yellow, short school bus picks you up at your home and takes you to a different school than everyone else,” he said of that time. “I couldn’t even go to Foothill. [Then, after I was diagnosed], I came back to Foothill back down the road. So they took a kid away from the public school system, one who didn’t need to be miscategorized, and then put him back in. By then, I was already behind every other kid.”

Wallace believes that most of the mistreatment he suffered was due to an absence of training for teachers, and a lack of understanding from other students. After his return to Foothill, he found himself often being pulled out of class for long periods of time to attend special education classes, and he could feel other students’ judgment for it.

Although he thinks the situation for students with learning disabilities has improved in recent years, Wallace still believes there is a stigma around children with disabilities, one that often starts in elementary school: “I will always say the stigma will never go away,” he said. “But now, teachers are generally more trained with working with students with disabilities. They understand that every kid has a different way of understanding.”

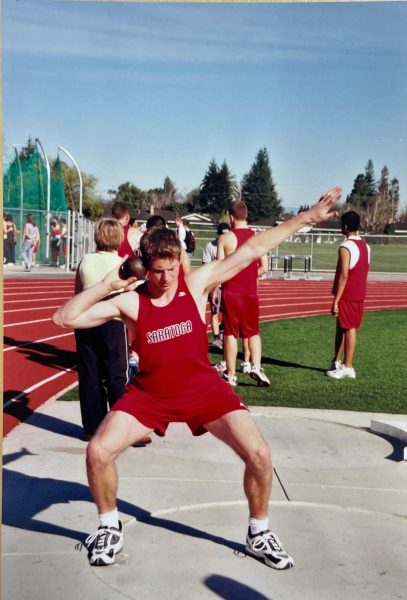

During his time in school, Wallace saw sports as a refuge — it was something that dyslexia did not affect. He felt that sports, something he was the best at in his time, made him feel better than anything else did.

Dan Wallace throwing shot put in his senior year.

Academics was tougher for him, but he managed to do well in high school. While he was not in a special education program, he was in a study skills class where there was time to work on his homework and get help from a teacher. His general education teachers also helped him overcome his dyslexia with extra help and support.

Majoring in Social Studies and minoring in Business at San Jose State University, Wallace found that the challenges he faced in high school continued to affect him. Dyslexia made some school work — especially long readings that other students found relatively easy to do — extremely time consuming.

For example, multiple professors would assign him 30 pages of reading a week, and, as it took him 10 minutes to read a page, it could take him over 1,500 minutes — or 25 hours — to complete a given week’s readings. Determined to succeed, Wallace decided to take advantage of his professors’ office hours to seek extra help outside of class.

“I told them that I would come to every office hour that I can find [time for], and we would have a sit down conversation on the book or chapter,” Wallace said.

Wallace recalls benefiting greatly from the personal help from his professors — they were willing to spend time and have a conversation on the important parts of the book or reading, helping him learn in a personalized, effective method. Wallace believes that it’s important for people to recognize their strengths and focus on playing at their strongest abilities. For Wallace, his strength was being able to find time to speak with his professors and understand the material through face-to-face interactions, as opposed to absorbing long passages of reading.

Wallace returns to Saratoga to teach others with special needs

In special education, there are three categories for students with disabilities: mild, moderate and severe. At SJSU, Wallace earned a teaching credential for mild to moderate special education, certifying him to work with such students.

“I wanted to show students that are in the mild to moderate disability category, like I was, that you can be successful: You can go to college; you can get a degree; and you can work in the workforce. Don’t let people tell you that you can’t just because you have a disability,” Wallace said.

The IEP program, in which Wallace is a veteran teacher, is a teaching program revolving around a written legal document that a student can be eligible for if they qualify as having a disability. It is similar to a map that lays out a program of special education services that a disabled student needs to thrive in public school. It provides individualized instruction and support for their education.

At the school, the Community Based Instruction (CBI) and Resource Specialist Programs (RSP) provide and teach curricula for students in the IEP program. The CBI program gives students with more severe disabilities the opportunity to go out into the community and better understand how society functions, while in RSP, where Wallace primarily works, students have modified general classes, such as in math, history and English. Wallace and other general and special education teachers develop the RSP programs together.

“There are students that are in general classes with IEPs, where they’re getting accommodations,” Wallace said. “Those accommodations aren’t meant to give them a leg up on anybody; they are just an accommodation to help keep the playing field equal, so that the kids can work towards [their goal].”

These accommodations include practices such as extensions on homework assignments and more time for tests. While the modifications are important for many students, Wallace believes some students should try to step away from them as much as possible. He believes that if they challenge themselves to do work without accommodations, they can improve.

“One kid might need a one-week extension on assignments, and another might need triple the time on a test because it takes them so long. That doesn’t mean every other kid needs that,” Wallace said. “I’m trying to make the kids understand that you hinder yourself when you rely too much on your accommodations.”

Wallace looks forward to the growth of the children who are in special education programs. However, he also hopes that the students don’t become dependent on unnecessary help; he believes that the ultimate goal of special education is to help students to tackle tasks on their own.

Through his own teaching, some of Wallace’s former students, despite their learning disabilities, have found great success beyond high school, in industries such as business, fashion, finance, health care and real estate. His experience as a dyslexic student before the establishment of strong special education programs has taught him that the most important thing to teach students with disabilities is how to succeed on their own.

“One day, I realized that I wanted people to stop helping me,” Wallace said. “I wanted to start doing more on my own. When I started becoming more successful when I was in school, I didn’t have accommodations. I wasn’t against the accommodations, but you shouldn’t be relying on the crutch forever; you have to walk.”