Junior Michael Cheung and four friends from marching band were surprised to find themselves called to the office during fifth-period band on Nov. 7. They soon discovered that their involvement in an on-campus game called Assassin was the cause.

Some groups playing this game had been playing for money—a form of gambling, according to administrators—and that’s when assistant principal Kevin Mount told students that the games, “legitimate and illegitimate,” had to be over.

However, the administration has since altered that decision. The game assassin is now allowed if played without money.

“If it involves gambling, then my line is no,” Mount said. “As long as the game is played for fun and doesn’t involve a wager and an individual’s chance to benefit, then bond on … [However], if anything is reported to the office that is a disruption of the learning environment and class, then we have to act.”

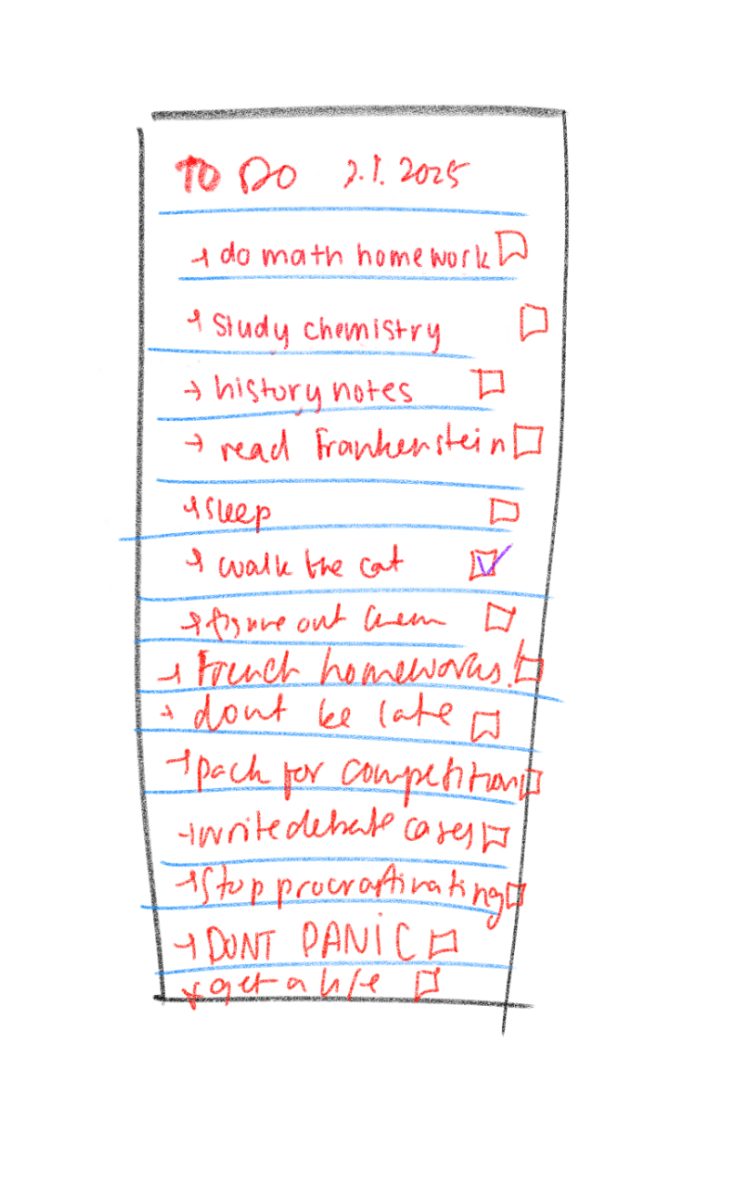

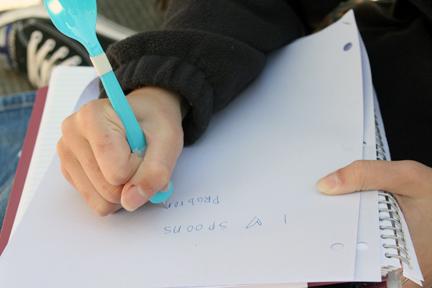

In most versions of the game, assassins receive their “targets” via email; it is their goal to “kill” the targets by tagging them with a colored spoon. A target cannot be tagged while holding his or her spoon. After all other players have been eliminated, the last one standing is deemed the winner.

According to Mount, administrators underestimated how many students were involved in the game and never made an official announcement of the ban. When the game was banned, rumors began to fly about the administration’s justification for doing so.

Like many other students, Cheung was outraged by the administration’s ban.

“I’m annoyed, the band is annoyed, basically everyone is upset about it,” Cheung said. “The way the administrators took the spoon shows that the school doesn’t respect the fun the students have around the campus … we’re all frustrated at the administration.”

Outrage over the ban also sparked protests. Senior Mark Van Aken, whose Facebook profile picture was a black spoon with a white star, created a Facebook event titled “Right to Bear Spoons Protest” that garnered 110 supporters in approximately five minutes and over 200 supporters in all.

“Bring a spoon that is colored to protest the ridiculous ban of the game assassin at the school and the ridiculous banning of colored spoons on campus that resulted from the banning of assassin,” Van Aken wrote for the group’s information.

On the group’s wall, students posted statements like “Occupy SHS,” “Down with the administration” and “I am bringing black armbands to store spoons. Let’s Vietnam this!”

Dozens of students protested on Nov. 10 by bringing multi-colored spoons to school.

Several small groups have played Assassin in past years; however these games were relatively low-key and had fewer participants. Mount was unaware of the game until an encounter with a student who, upset over losing money in the game, attracted the attention of administrators.

“It’s unfortunate that kids have aberrant behavior that ruin it for good kids,” assistant principal Karen Hyde said. “What started off as great for journalism and band was brought to lower levels by those who had bad intent, in that kids [in some] game.”

Several students agreed with the administration’s point of view.

“There is no efficient way to regulate who is gambling and who is playing for fun,” junior Michael Shang said. “The administration has other things to worry about than the legality of kids running around with spoons.”

Other students disputed the “gambling” charge, claiming that the concept behind assassin is no different from that of a raffle, where one pays money in hope of obtaining a larger prize.

“If we ban assassin, we might as well ban raffles,” sophomore class representative Gloria Liou said. “I think the administration just doesn’t like how the money isn’t going through their hands. Besides, the most someone can lose is like $10, which is really not worth canceling the entire thing.”

Mount, however, disagreed.

“Typically in a raffle there’s an agreement around the group that they’re going to do this for a cause,” he said. “The money itself is managed by a trusted agent. There were [assassin] groups who didn’t know who was in the group and how to get the money back to [individuals].”