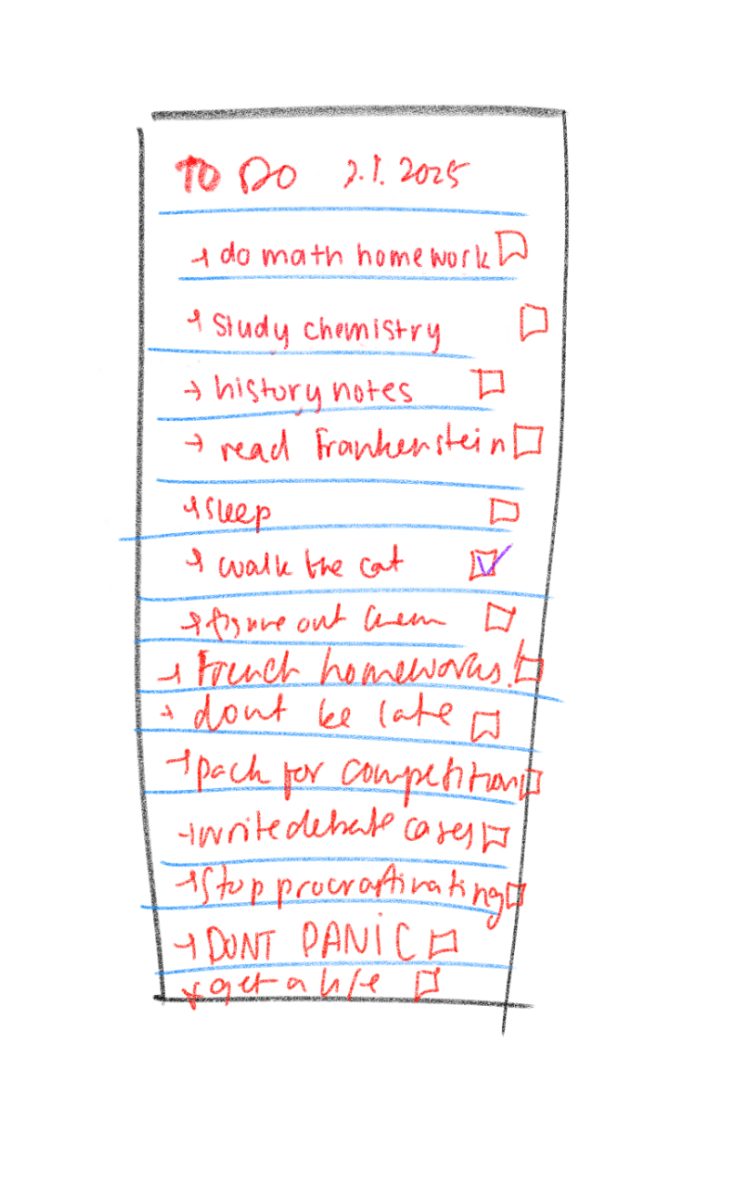

On Tuesday evenings, students from Redwood Middle School’s math club (TJMC) meet in empty classrooms to learn and prepare for competitions. There are four groups: yellow, green, blue and black — blue and black are for more experienced students, while yellow and green are meant to introduce lower grades to the foundations of math.

Senior Stuti Agarwal recalled a roughly equal balance of boys and girls in the yellow group as a sixth grader. She said there were many people she could talk with and relate to, so she was never left out.

However, when she qualified for the blue group the next year, only six of the 18 students were girls. A year later, Agarwal was the only girl in the five-person black group.

A similar situation also occurred in the Mathcounts Squad, in which 12 students were selected — Agarwal and senior Dyne Lee were the only two girls. Lee has noticed the same trend as Agarwal.

“In middle school, when I took classes, there were a decent number of girls,” Lee said. “Now, it’s completely different. When I take advanced classes, there’s usually only two or three girls in the entire class.”

The Bay Area, and especially a city like Saratoga, is concentrated with high-earning immigrants, many of whom have liberal-leaning political and social beliefs. Many students have high-achieving role models in their parents, relatives and friends — they don’t have to look far to see someone highly successful in their prospective field.

Despite this seeming progressiveness, there is still a prevalent gender gap in terms of achievement and representation in mathematics. This gap can lead to intrinsic struggles for the girls who are high-achieving in math and other STEM fields.

The mindset

Agarwal said that living in the Bay Area has eased many of the potential struggles of being a girl striving to be high achieving in mathematics.

“I’ve grown up in a community where everyone has been super supportive of all genders doing math,” Agarwal said. “I think my journey would have been different if I was in a different place or time.”

At first glance, this mindset of an even playing field for all genders in mathematics makes sense given the wealth in Saratoga. According to the Pew Research Center, well-to-do parents are far more likely than less affluent adults to claim that they believe in equal opportunities, and more likely to not hold any preconceived notions for all genders in any subject.

However, while parents in high-income areas may spend more time and money on their children, they also invest in more gender-based stereotypical activities. Daughters are often encouraged to join ballet, while sons are prodded into engineering. According to the World Economic Forum, the presence of startups and technology in the Bay Area creates a bubble that fails to recognize that rapid progress in technology is not representative of rapid progress in societal norms. Despite California’s progressive and liberal culture, many adults inadvertently fall into the trap of creating an environment where the gender gap between girls and boys in fields like science and mathematics is more pronounced than ever.

The wrath-achievement paradox

In 2018, Sean Reardon and Erin Fahle, two sociologists from Stanford University, published a comprehensive study on the gender gap in middle school standardized test scoring. The study found that income and poverty seem to have little impact over the gender gap in English tests, where girls consistently outscored boys.

The study showed that girls performed almost an entire grade level ahead of boys on average in humanities classes. Not only was this trend true in low-income places like Detroit, Michigan, and Birmingham, Alabama, but also in well-off districts such as the Cupertino Union School District (CUSD).

In math, by contrast, the gender gap noticeably widened as the income-level increased. Two of the top five districts in the entire nation in terms of family income, as measured by the study, were in the Bay Area: CUSD and the Los Altos School District (LASD) — the trends in the Saratoga Union School District (SUSD) were not explored in the study.

In the study, boys in most Bay Area school districts outperformed girls by about four months on average in math. This means that they were approximately half a grade level ahead in the subject. In comparison, boys outperform girls by about a month on average in math in the entire nation.

On the other hand, in about a quarter of districts consisting of mostly low-income areas, girls performed better than boys in math. In Detroit, for example, the median income is $19,000, about 10% of the median income in Saratoga. Despite this, Detroit is one of the places where girls perform best relative to boys. Girls in Detroit are not only far ahead of boys in English, but also approximately two months ahead of boys in math.

So, why does the apparent gender gap in math in high-income areas occur?

According to research by Dan Clawson and Naomi Gerstel, two sociologists from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, men in high-income areas often earn the majority of household income.

Men in such areas are also paid higher in the industry on average, have higher levels of education, work in high-paying fields and are more likely to marry women who did not have such high levels of achievement and credentials.

The researchers think that because children are likely to emulate the pattern of their parents, there is a trend of high-earning parents relegating their children to “gender-appropriate” stereotypical activities, creating a gender-based divide in different disciplines.

While different genders have been found to have different preferences and tastes in their interests, the gender gap that starts very early in life tends to persist stubbornly throughout college, in the workplace and beyond.

A widening gender gap in math activities

Even though students in the Bay Area, especially in high-income areas like Saratoga, consistently outperform the national average, the gender gap between test scores has been continually widening. This is perhaps best reflected in prominent elite math competitions, which include the AMC-AIME-USA(J)MO series.

Seventy-seven students from Saratoga High took the AMC 10 and 12 in February 2021. Out of these test-takers, 29 were girls, a boy-to-girl ratio of 62.2% to 37.8%. Similarly, according to the Mathematical Association of America (MAA), about 37.3% and 34.8% of participants of the AMC 12A and 12B, respectively, across the nation were girls.

To qualify for the next test — the American Invitational Mathematics Examination (AIME) — students have to score in roughly the top 2.5% of the AMC 10 or roughly in the top 5% of the AMC 12. According to MAA’s released statistics, out of the 6,350 students who took the 2021 exam, only 1,340 were girls, a boy-to-girl ratio of about 78.9% to 21.1%.

Only 34 girls nationally got a double digit score on the 15-question test, compared to 312 boys. The six who achieved perfect scores on the exam were boys.

The widening gap that occurs at higher scores means that the highest scores are achieved almost entirely by boys. In particular, as the gender gap increases at higher levels of achievement in the world of elite math contests, and girls start improving in the field, they find fewer people they can relate to.

Agarwal said that she has seen this trend throughout her experience with math competitions since elementary school. In middle school, as she moved from Redwood’s entry-level yellow group to the most competitive black group, the lack of other girls contributed to feelings of isolation.

Standardized Testing

Similar trends occur in the College Board’s SAT, designed to help colleges make more informed decisions on students’ academic ability in a standardized way.

According to data collected by the College Board, there is little gender gap when comparing girls to boys at the median percentile level (50th percentile). When comparing the scores of girls and boys at lower percentiles (such as 25th and below), there are a slightly larger number of girls.

On the other hand, at higher percentile levels, there are a larger number of boys. In fact, at the highest score levels of approximately the 99th percentile, the male-to-female ratio becomes approximately 70% to 30%. For example, the male-to-female ratio for perfect scores that year (2010) was 67.5% to 32.5%.

Since elite colleges often nearly exclusively accept students who scored in the 99th percentile on this test, the widening gap harms girls who would otherwise benefit from the upward mobility provided by highly selective institutions.

School courses show gaps

The gender gap also exists in advanced math and physics courses at Saratoga High. Since these are fundamental classes to pursuing math, physics, and other STEM fields in college, the implications of this transcend just the high school level.

According to the school’s enrollment data, AP Calculus BC classes are composed of 34% girls and 66% boys. This is an all-time low out of the last five years, with the breakdown being 44% girls and 56% boys as recently as 2019.

For the school’s AP Physics C class, which requires its seniors to have completed a course in AP calculus and a course in AP Physics, only one student in the entire class was a girl last year. This year, the ratio is better, but the class is still only 30% girls. AP Physics 1 and 2 courses have also had a similar breakdown of approximately 30% girls and 70% boys over the last few years.

Physics and calculus are prerequisite courses to majoring in math, physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering, and so a strong foundation in these fields in high school are important for students interested in exploring quantitative fields in college.

Girls struggle socially in male-dominated competitions

Agarwal believes that the extremely skewed boy-to-girl ratios in clubs and competitions have impacted her experience positively and negatively as both a student and a contestant.

“There were so many boys that it was just overwhelming or intimidating at times,” Agarwal said. “I didn’t always feel like I belonged.”

Lee said she felt similarly and that it was often discouraging to be “in a room full of guys and only one or two girls, trying to solve math problems together.”

She said being a girl in math is mostly a socioemotional problem — if more girls felt comfortable enough to participate and take part in activities such as clubs and competitions, the disadvantage could be resolved.

“It was never directly disadvantageous,” Lee said. “No one ever came up to me and insulted me, or made me feel that I was not welcome there. It’s just socially difficult to bond with people when there are less that you can relate with.”

According to mathematician and New York Times bestselling-author Catherine O’Neill, competitions can make young people think that they aren’t cut out to be mathematicians. Women are particularly susceptible to feelings of not being talented or good enough to do things.

A study by Glenn Ellison and Ashley Swanson adds that “an 11th grade boy with a score just below the AIME cutoff will be almost as likely to drop out of participating as an 11th grade girl who scored just above the cutoff.”

Ellison and Swanson found that this often starts with parents: When comparing parents of talented girls to talented boys, the parents of the boys were more likely to send their child to a school with a nationally elite math program.

Lee said that she has received the best possible education that she could have in the Bay Area, and that the number of opportunities and resources that she has is enough for her to achieve her goals and dreams in the subjects.

She added that the best way to succeed in an atmosphere where the number of girls is severely limited is to simply reach out to other people, and try to find people with similar interests and ideas.

Despite this, Agarwal said that there are relatively strong stereotypical notions about who “gets to do math” and who doesn’t — even though she sees it less in the Bay Area than in other places.

In her perspective, math is seen as a male-dominated field. Boys are often pushed in that direction, while girls are often pushed away from it.

As the sole girl in many specialized classes that are instrumental to doing well in competitions, Agarwal said she faced the challenge of proving stereotypes wrong — if there’s only a single girl in a class, then the way she behaves has more profound consequences. The lack of other girls with similar interests inside of clubs or competitions made Agarwal feel that she was the ambassador of her gender.

“I wasn’t sure whether I would look stupid,” Agarwal said. “I was afraid to ask questions. I was afraid to give answers. I was afraid to open my mouth.”

Eventually, however, she learned to get past these uncomfortable feelings and to embrace the idea of making mistakes in order to learn.

“The hardest part of being a girl in mathematics is just finding a community that makes you feel comfortable,” Agarwal said. “Once you get over the initial feelings of self-doubt and overcome the fear of asking questions, you feel fine.”

Traditional competitions make changes to promote female participation

The International Math Olympiad (IMO) is the oldest of the international high school science olympiads. A study by the American Mathematical Society, co-authored by former USA IMO coach Titu Andreescu, looked at the gender gap and found that in most countries, the six-person IMO team rarely contained an equal proportion of boys and girls.

From 1988 to 2008, in which each country sent roughly 120 participants, most countries had less than 10 girls in total.

At the competition, boys outnumbered girls so much that the trend was given a colloquial name: the 10 percent rule, describing the competition’s unbalanced gender distribution.

In response to the unbalance, some programs have implented affirmative action policies, which are any set of policies that set in place to counter past discrimination against minority groups like women. A notable example is the prestigious math summer program Math Olympiad Program (MOP).

Most campers at MOP are male. This led to the creation of a program called “Pink MOP,” a set of 10 to 12 girls selected to maintain inclusivity for all genders and train female members for international math competitions like the European Girls Math Olympiad (EGMO) and the China Girls Math Olympiad (CGMO). The MAA has also started to constitute gender balancing for its USAJMO and USAMO examinations, lowering the cutoffs for girls.

On an Art of Problem Solving thread, users were concerned about the message that MAA’s initiatives were sending to female contestants. By lowering the cutoff, one user wrote, MAA was effectively telling girls that “we’ve lowered standards for you because you aren’t good enough.”

Lee believes that analyzing whether affirmative action is actually beneficial to participants is complicated.

“On one hand, it can encourage female contestants and open up new opportunities,” Lee said. “On the other hand, it could also cause feelings of imposter syndrome.”

Tournament organizers also often host special awards for the top female participants to increase female participation.

The most prominent of these is hosted by MAA for the AMC examinations. The awards, known as the “Awards and Certificates Program for Young Women in Mathematics,” are some of the few awards offered to students by the MAA.

The AMC 10A award is named after the most successful female mathematician of all time, Maryam Mirzakhani, who was the first and only female mathematician to ever win the Fields Medal. The Fields Medal is the most prestigious prize in all of mathematics, and is the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in the field.

Juniors Lisa Fung and Isha Jagadish earned the Maryam Mirzakhani 10A Certificate of Excellence and the Akamai Foundation 12B Certificate of Excellence in 2021, respectively. Additionally, freshman Ishani Agarwal won the D.E. Shaw AMC 8 award and a monetary bonus.

In an email announcement, MAA said the purpose of female awards is to use the support of donors to improve the inclusivity of all genders in mathematics and to “create a community of young mathematicians who are supported at every stage of their journey.”

Lee believes that these awards are highly motivating and useful for any girl who has qualms about joining the mathematical community. Knowing that she can be recognized for her achievements in mathematics is a strong incentive.

Organizers create female-only competitions

Some competition organizers, like the MIT department of mathematics, host all-girl math competitions like the Math Prize for Girls, the most famous math tournament available only to female and non-binary participants.

MIT said the competition’s purpose is to “promote gender equity in the STEM professions and to encourage young women with exceptional potential to become mathematical and scientific leaders.”

The tournament awards a total of $50,000 in prizes, including a $25,000 monetary award for the top individual. This is the highest monetary award in any high school mathematics competition, making it highly lucrative for test takers.

Agarwal and Lee were both accepted and allowed to participate for the first time in the 2020 tournament, which was virtual.

The tournament hosted speaker panels to expose high-achieving girls to what a career in STEM is truly like and to provide them with female role models, so that they wouldn’t feel alone in a chosen career path.

The main benefit of attending, according to Lee, was the social experience of meeting many girls who enjoyed mathematics and related fields.

“I got to meet other girls who like doing competition math,” Lee said. “It was pretty helpful to see other girls similar to me, going through the same experiences as I was.”

Agarwal believed that the tournament was a stark contrast to the other homogenous tournaments that she had participated her whole life up until now, where she found it difficult to relate with others.

Others believe that such tournaments are not truly meeting their goal of exposing more people to STEM-related areas, because all the participants in Math Prize for Girls Prospective participants must apply to be able to compete at the tournament, due to space constraints.

The process is selective and requires success in mainstream competitions such as the AMC. As a result, most competitors are already highly involved in math competitions at the time of participating.

“I definitely think it can be sort of discouraging to people who can’t or didn’t qualify,” Lee said. “We need to see a growth of competitions and resources that are open to anyone.”

Lee said it would be better if there were more tournaments with a similar philosophy, so more girls involved in competition math could be exposed to similar social scenes.

The effect of the gap later on in life

According to a report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (O.E.C.D.), the gender gap in mathematics and other STEM subjects starts very early in life and persists stubbornly till the collegiate level, in the workplace, and beyond.

At U.C. Berkeley, the engineering department was 32% female in 2021, up from about 22% in 2012. At MIT, the engineering department was 32% female as well in 2020.

According to a survey conducted by MIT’s math department, women composed 52% of doctoral degrees, but only 29% of doctoral degrees in mathematics and statistics. The same survey found that the percentage of senior lecturers who are women is only 10% of senior lecturers at “Group 1” private institutions and 4% at Harvard.

Though women represent 46.8% of the workforce, only 25.5% of them have a job categorized as “Computer and Mathematical Occupations.” There are gender equity concerns about the wage gap — females currently make 82% of their male counterparts on average, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Additionally, the STEM field is becoming increasingly central to the gap, as the high wages and wide gap make it a major contributor.

One recent paper by Georgetown found that just grades alone rarely prompted a change in major for women leaving STEM — rather it was a combination of grades and the negative stereotypes that forms the environment in which they live.

An example of these negative stereotypes can be found in consumer marketing, which perpetuates them in a sexist manner. For example, fashion brands such as Forever 21 and JC Penney sold young women shirts that had phrases such as “allergic to algebra” or “I’m too pretty to do homework so my brother has to do it for me.”

Even in the heart of Silicon Valley itself, there is a subculture in the tech industry of brogrammers, the so-called display of masculinity in programming.

How can these problems begin to be solved? Lee points to the idea of having more opportunities like math prizes or other resources for girls, including helping with the social and emotional parts of competitions.

“We should be trying to get more girls to participate,” Lee said. “Even if they don’t do so well at first, it’s still highly important.”