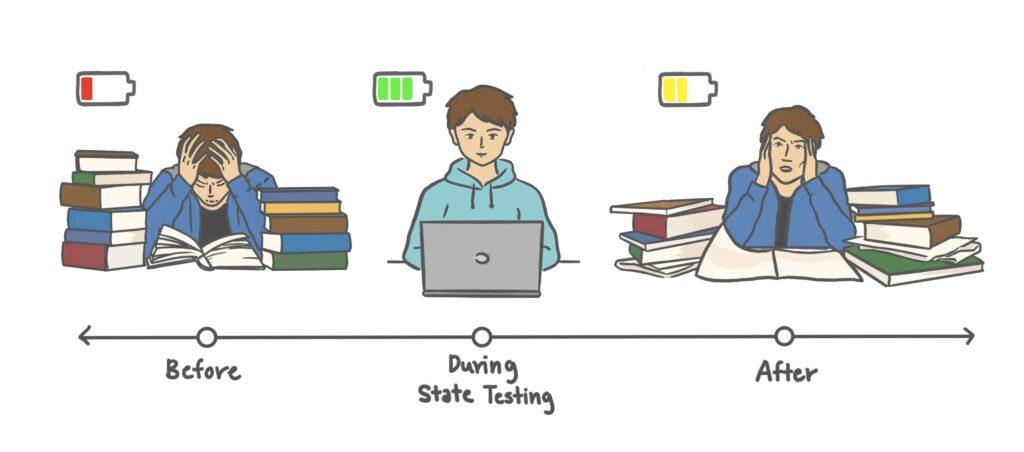

When I took my first ever SAT in November, I went in with the expectation that I would take it no more than twice. After all, I could always go the test-optional route if the retake didn’t work out. Unlike a lot of my friends, I was quite a novice at standardized testing: I had only taken one PSAT and had never set foot into a paid prep class or tutoring session, instead self-studying using the College Board’s Khan Academy SAT prep resource and a secondhand prep book.

My score was much better than I expected and I was overjoyed. But when I spoke with a friend about it, she advised me to take it again to increase my math score. I was confused: I didn’t want to risk a lower reading (and perhaps, overall) score on my retake just for the sake of doing better on another section.

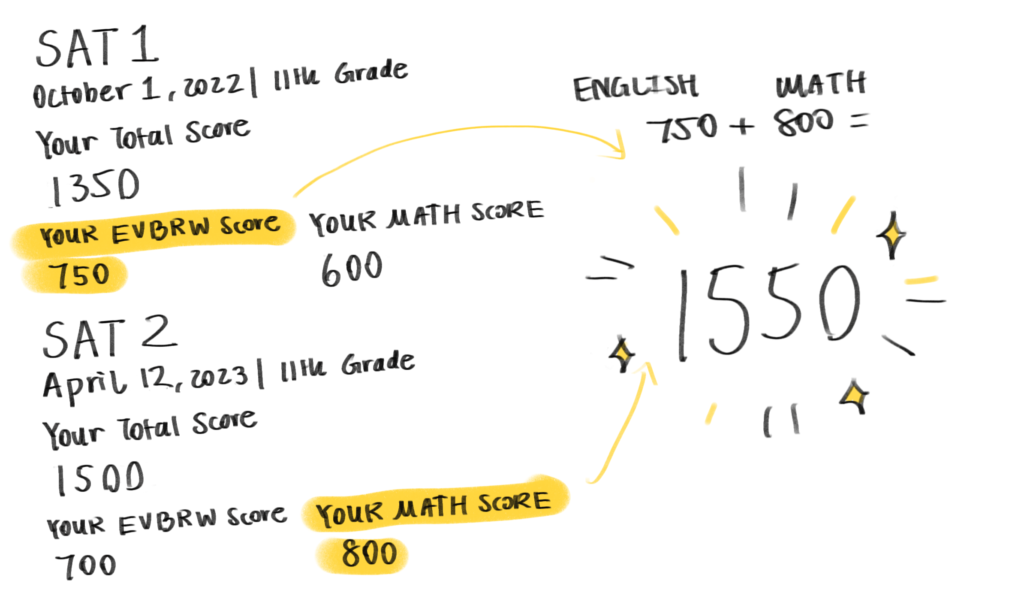

That’s when I learned about superscoring.

With superscoring, students can take the SAT more than once, with their highest score over all sittings from each section added together to gain their best score. This incentivizes students to retake the test over and over until they have maximized their score for each section.

While it may come as a boon to some who may perform better on any one section than the other, encouraging retakes to fine-tune scores is a harmful practice that undermines the entire point of a standardized test.

By design, the SAT is an aptitude test designed to measure knowledge without significant preparation — scoring in the 50th percentile indicates meeting 8th grade level reading and math benchmarks. For students that need help with content, the SAT’s free Khan Academy prep resource provides all students with the necessary skills and content for SAT proficiency. Past that, the SAT is simply a test of your test-taking skills.

Because of this, a student’s socioeconomic background is a strong predictor of their performance on standardized testing. The monumental growth of the test-prep industry, which rakes in hundreds of million dollars a year from prep books and private tutoring services, is a testament to the financial lengths affluent families will go to in order to game the test.

When superscores are added to the mix, the entire point of the SAT as a standard of aptitude is undermined further. If a student takes the test over and over with incremental increases each time, how well does their superscore actually reflect their abilities? Hint: It doesn’t.

Time, resources for preparation and access to testing centers put affluent students at a further advantage when it comes to retake opportunities. Affluent students can also afford the $75 registration fee more than twice — while the College Board offers fee waivers, they apply for only two registrations (one test and up to one retake). This means that only students who can afford to pay the fee can afford to retake the test more than once. These are the students who inevitably benefit the most from the superscoring policy.

Encouraging multiple retakes also places an emphasis on spending increasing time and money on a test with diminishing relevance. As more colleges go test-blind or test-optional, there is always the option to apply to colleges without submitting the scores. So why are we still encouraging students to take and retake an exam for which the median score benchmark is eighth-grade reading and math?

Standardized testing is supposed to be an equalizer in college admissions. The entire point of the SAT is that regardless of differences in rigor of individual schools or the extracurricular opportunities available to each student, basic aptitude in reading and mathematics can be captured through a standardized exam with a quantitative score that can be easily evaluated by colleges. Superscoring goes against every one of these principles.

A possible solution to the current superscoring dilemma could involve taking the average of all attempts on a section to compose a final score rather than taking the raw score — this means that retaking would not make sense unless there significant improvement is guaranteed, disincentivizing students from simply taking it repeatedly. The College Board should also place a cap on the number of retakes allowed for all students, not just poor ones.

When it comes to the relevance of the SAT itself, there are plenty of good arguments on both sides of the debate. But with superscoring, there isn’t any good argument to support it — and it needs to go.