Note: The print version of this article contains slight errors in the section about Dahlia Murthy. The web version was updated accordingly. The corrections are as follows:

1. Murthy’s father was raised in South India, not North India.

- Murthy later clarified that her mother took it on herself to cook Indian food independently through recipes from Indian relatives and Indian cookbooks, not solely through Murthy’s father’s encouragement.

For many first- and second-generation South Asian American youth, coming to terms with their cultural and ethnic identity is a constant struggle between fitting in with peers and holding onto heritage. This conflict is a central aspect of the South Asian American experience — but multiethnic South Asians are often excluded from the conversation.

Multiethnic South Asian American families typically have very different experiences with ethnic identity than families from a single culture or ethnicity. Besides being extremely underrepresented in South Asian communities, these multiethnic families navigate distinctive issues such as cultural differences in parenting, religious conflicts and interracial relationships.

While interracial marriage has become increasingly normalized in America, South Asian Americans are still more likely to marry people of their same ethnicity. There has even been a drop in the percentage of Asian Americans who married outside of their race in the past few years, falling from 33 percent in 1980 to 29 percent in 2012. Additionally, the “cultural closet” — the stigma associated with interracial relationhips — is still prevalent among South Asian circles.

As a result, many people often overlook the challenges and experiences of multiethnic South Asian American, a school where the majority of the student body is Asian American; many of the multiethnic South Asian American students have very different experiences from students who are Indian Americans and Pakistani Americans, for example.

Struggling to fit in

Ever since senior Maya Vasudev was a child, she and her family loved visiting San Jose’s Little Saigon, home to many Vietnamese American people as well as an abundance of Vietnamese shops and restaurants. Her mother, who is Tai Dam — an ethnic minority near Vietnam and Laos — often took Vasudev and her siblings there to visit.

On one of her family’s visits to Little Saigon, Vasudev’s mother and sister were sitting on a bench waiting for Vasudev to finish shopping. Throughout the day, Vasudev had noticed that she was treated differently than her siblings and she knew why.

Vasudev said that, unlike herself, her mother and grandma — who are both Tai Dam — and her sisters looked like the majority of shoppers in Little Saigon.

Vasudev’s mother and grandmother are light-skinned Asians, and her sister is white-passing. Vasudev, however, has brown skin.

As Vasudev approached her family on the bench, a woman sitting next to her family got up and moved away.

“I sat down and the lady gave me a weird look and moved all the way to the other side of the bench,” Vasudev said. “The reason why that hurt in particular is because my family is literally from Vietnam. I realized that even with people who are your own or close to your own — they sometimes won’t want you because you don’t look like them.”

Vasudev is half Vietnamese, a quarter South Indian and a quarter white — her mom is Tai Dam and her dad is half Norwegian-Lithuanian and half South Indian. She said she has had a difficult time grappling with her identity and figuring out how to connect equally with all parts of her background.

Vasudev felt pressured to choose a single part of her culture to connect to, and didn’t realize that she could identify as multiracial until two years ago. She felt like she had to ‘pick and choose’ between her cultures when asked what race she was, and didn’t realize there was a label for people who were of multiple races.

Since Tai Dam people are a very small indigneous minority, Vasudev said she felt more motivated to learn about that aspect of her heritage. Due to her Indian and white heritage, she looked different from most of her mother’s relatives and she said that she struggled to feel like she was actually Tai Dam.

According to Vasudev, she was not exposed to her father’s culture much, since she was never truly close to his family. She also found herself denying parts of her Indian heritage and disengaging from family events due to the effect colorism had on her.

“I never really involved myself in [Indian] culture that much as a kid,” Vasudev said. “There was this one time where we went to India and went to my relatives’ house. [In certain Indian cultures] when you leave the house, they’ll give you a [tilak]. I didn’t know what it was so I just wiped it off. I think it was more of, ‘I don’t want anything to do with that because I don’t want to be [Indian].’”

Because of this, Vasudev struggled to connect with Indian Americans as well as the Vietnamese American students who she said didn’t look like her and often had different cultural experiences than her at school.

Another factor that prevented Vasudev from relating to her different ethnicities was the language barrier: She isn’t fluent in Vietnamese, Hindi or Kannada, the southwestern Indian language spoken by her dad’s family. Vasudev added that she was never exposed to these languages growing up, which she regrets.

“It’s kind of sad because language, in particular, is something that people bond over, and I never had that,” Vasudev said.

Although Vasudev struggled with her identity for a long time, she came to the realization that it is important for her to acknowledge all parts of her heritage equally; recently, she has been making an effort to connect with her Indian family through attending family events, speaking more to her father about his childhood and trying more Indian food.

Strong figures in her life like her grandmother have helped her come to terms with her identity. Vasudev recalled opening up to her grandmother about not looking like many people from Tai Dam, and remembered her grandmother saying that she would always be Tai Dam regardless of her appearance.

“I know that it may just be something that’s little, but it really does mean a lot to me,” Vasudev said.

Reconnecting with South Asian roots

When freshman Dahlia Murthy’s classmates called her a “coconut” in third grade, she didn’t understand what it meant. Murthy eventually realized why people had assigned the nickname to her; it was the same reason strangers in shopping malls unabashedly asked her if she was adopted when she was out shopping with her mother.

“When they called me a coconut, they meant I was brown on the outside and white on the inside,” Murthy said. “And when I got older, I realized that that’s probably what people would see me as for the rest of my life.”

Murthy’s father was born and raised in South India, while her mother — of Scandinavian descent — is white. Murthy’s parents met in San Francisco after her father joined the hospital where her mother worked.

Initially, her father’s side of the family was skeptical and dismissive of their relationship because her mother was Caucasian. But over time, her father’s family overcame the cultural stigma around interracial marriage and accepted Murthy’s mother as one of their own.

Murthy’s late grandmother on her mother’s side helped Murthy connect to her Scandinavian heritage by translating Finnish literature and poetry to English.

Connecting to her Indian culture was a bigger challenge for Murthy. Her Indian relatives in the U.S. mostly lived on the East Coast, and she only got to see them on holidays like Thanksgiving. Murthy felt her family was isolated from their extended South Asian relatives; her parents were known as the “West Coast Murthys.”

Despite growing up in Saratoga, which has a thriving Indian community, Murthy said she didn’t take the time to immerse herself in Indian culture.

“I was never able to relate to the ‘growing up Indian’ experience other people talk about,” Murthy said. “It’s definitely one of my regrets — that I didn’t spend enough time experiencing that side of my culture when I was younger.”

Her father helped her find ties to her culture through food, one of the most significant aspects of Indian culture. Murthy explained that her dad puts effort into introducing her family to Indian dishes, and her mother is skilled at cooking Indian food as well – she took it on herself to learn from family recipes and Indian cookbooks.

Despite her early struggles in connecting to her Indian heritage, Murthy has made peace with both sides of her culture. She plans to partake in more cultural activities over the course of high school, like the annual Bombay in the Bay production held by the Indian Cultural Awareness Club.

“I definitely have some regrets and do wish that I incorporated more of the culture on both sides of my family, but it just didn’t happen,” Murthy said. “It’s something we live with and I think I’m finally okay with that. I’m incredibly proud of both sides of my culture, and I’m going to keep trying to be more connected [to them] in the future.”

Finding balance among religious and cultural division

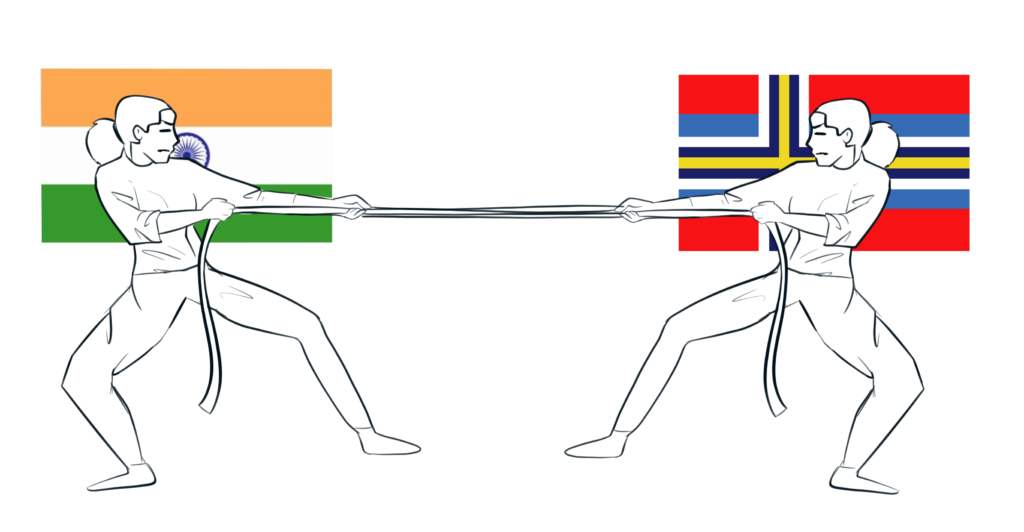

Junior Maaheen Khericha recalls watching cricket with her family a few years ago. The age-old rivalry between India and Pakistan came to life on the television screen and Khericha found herself conflicted. Which side was she supposed to be rooting for — Pakistan for her mom or India for her dad?

Khericha has felt the weight of being half-Indian and half-Pakistani from an early age. While the countries are neighbors and their people share common origins, the cultural, political and religious divides are significant.

India and Pakistan have had hostile political relations for decades following the Partition of India in 1947. Pakistan consists of an overwhelming Muslim majority, while India has a Hindu majority — contributing to cultural and religious differences between the two countries. Khericha said that her mother tends to be more conservative than her father, an effect of those cultural differences.

In addition to being half Pakistani and half Indian, Khericha’s family is Muslim; her mother is Sunni and her father is Shia. She said this caused her to feel alienated in the primarily non-Muslim Indian community at Saratoga.

“It’s definitely harder because I don’t fit into either group completely,” Khericha said. “There are different cultural aspects I can’t relate to because I don’t even know what they are — even for something as simple as food. But when it comes to Pakistani people, they look at me as more Indian. So I have to find a balance between my two cultures.”

Khericha often wanted to stand out from her primarily Indian peers when she was younger, as she felt being Pakistani set her apart. As a result, she often introduced herself as Pakistani, downplaying her Indian heritage. But now, she has been trying to embrace her Indian side more in an attempt to fit in with her friends rather than stand out.

Another struggle Khericha said she dealt with was balancing the difference in social norms between India and Pakistan, which, from her experience, is more conservative.

Khericha added that her Indian father is more open to discussing topics like clothes and religion, which she has a difficult time talking about with her mother.

Despite these conflicts, Khericha has been able to understand and come to terms with her identity over the years. Many of the other Pakistani students at the school are her family friends. She also gets to express and indulge in her Indian culture in her close social circle at school.

“Being surrounded by so many other [South Asians] really helped me accept all the aspects of my background,” Khericha said.

Relishing the diversity of a multicultural upbringing

Sophomore Jarrett Singh’s parents’ interracial marriage has always been a major source of family conflict. While his parents were both born and raised in Malaysia, his father is of Indian descent and his mother is of Chinese descent.

Singh said he has memories of his mother’s tension with her parents, both of whom opposed her marriage to an Indian man; his paternal grandmother was also against the marriage because she wanted his father to marry an Indian woman.

“Although I didn’t know my grandparents because they passed away when I was young, I know my mom is still bitter that my grandparents were willing to hold her brother’s kids, who are fully Chinese, but didn’t want to hold her own kids,” Singh said.

Despite these family’s issues, Singh is on good terms with his aunts, uncles and cousins in China and Malaysia. Though building relationships with them was difficult because of the geographical distance, his extended family was accepting and friendly when he visited them in Asia.

Singh said his parents’ Malaysian upbringing had just as much of an influence on their parenting as their Chinese and Indian cultural backgrounds.

He believes that the differences in Chinese and Indian culture that would typically be present in a multiracial relationship are much less drastic in his parents’ relationship because they both grew up in Malaysia — despite the lack of cultural assimilation between different ethnic groups in the country, his parents were exposed to many different cultures growing up.

According to Singh, growing up surrounded by cultural diversity in Malaysia made his parents much more comfortable with being in an interracial relationship than they would have been if they were raised in India or China.

Another important factor in their parenting styles is that Singh’s parents served in the military before college — as a result, Singh explained, his upbringing was “military-style” with strict rules and routines, which heavily contributed to his sense of discipline today.

Although he feels a slightly stronger connection to his Chinese side due to stronger family ties to his mother’s relatives, Singh stressed that his family still makes an effort to participate in both Chinese and Indian culture. In addition to participating in important holidays from both cultures, he said he has a strong connection to his culture through food.

“We shop at India Cash and Carry as much as we do at Ranch 99,” Singh said. “There was never a question of whether we would have a Chinese lunch or Indian dinner — things were always very mixed.”

Even though his family is multiracial, Singh has always felt welcome and included in the Saratoga community. Because of the large percentage of both Chinese and Indian students, he said his mixed race background has rarely felt like a burden — instead, Singh appreciates the diverse perspectives and experiences he was exposed to as a result of his unique cultural heritage.

“I don’t think I’ve faced any discrimination here in Saratoga,” Singh said. “It’s helped me enjoy the experience of being multiracial, rather than worry about it.”