What could an all-girls public high school in New York City have in common with Saratoga High? Judging by the experience of Hedy Yuen, junior Sofia Chang and senior Arthur Chang’s mother, more than one may expect.

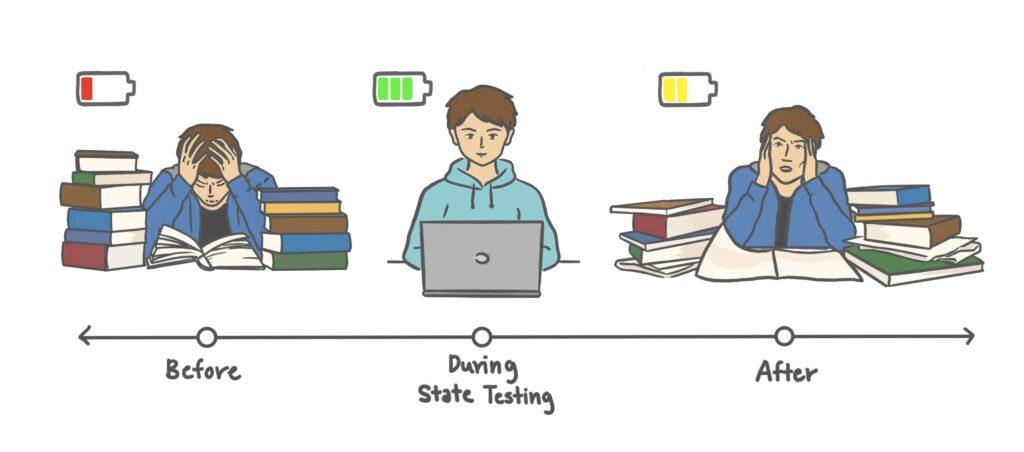

An immigrant from Hong Kong at age 11, Yuen at first struggled to make the transition to life in America. While attending the inner-city Washington Irving High School near Union Square, Yuen felt the same pressure to excel academically as many students here; however, her stress did not have the same origins as that of her children and other students. To Yuen, good grades not only meant pleased parents or a good future career, it meant opportunities that could change her life.

“As a struggling first-generation immigrant, I knew that education was my ticket out of poverty,” Yuen said. “Whatever pressure I felt to do well in school was strictly self-imposed.”

Although her school had few resources and no AP classes, Yuen strove to learn as much as she could and tried her best in order to ready herself for college, drawing pressure from within instead of from a competitive atmosphere such as Saratoga.

“I think there is a lot more pressure on high schoolers nowadays to succeed, especially in Saratoga,” Sofia Chang said. “My mother didn’t have that sense of competition around her.”

Even without the pressure from other students, Yuen always harbored a desire to attend a good college, making both taking the SAT and earning high grades very important, leading her to the title of her class’s valedictorian and a spot at the prestigious Radcliffe College.

“I resisted taking the easy route of relying on my natural affinity for math and science,” Yuen said. ”I pushed myself to work harder in subjects that were more difficult for me.”

Outside the classroom, everyday activities of a Saratoga student usually include extracurriculars such as marching band, speech and debate, sports or a part-time job, followed by homework and any sleep that can be squeezed in before school the next day; Yuen’s schedule was possibly even more jam-packed.

“I worked most evenings in a ‘sweatshop’ in Chinatown,” Yuen said. “I was involved in math team competitions, science fair, Girls Scouts, and peer tutoring.” Even with so many responsibilities, Yuen was able to sleep for an average of six hours a night, similar to many Saratoga students.

With the lessons she learned through her self-motivation and goal-setting in life, Yuen now strives to maintain realistic standards for her children, urging them to “take responsibility for their success” and find a “meaningful career based on interests.” Following her own advice, Yuen went on to work at several art museums before becoming a mother.

While Chang believes that some parents do not understand that “sometimes high schoolers want a life outside of preparing for college,” she feels “lucky that my mom’s expectations are just for me to do the best that I can.”