Along the trails and roads leading to the historic Montalvo Villa, groups of adults from around the country, all decked in various wrapped garments and vivid, traditional South Asian clothing, flocked this past fall to hear from some of the world’s leading South Asian scholars and highly acclaimed artists.

The South Asian Literature and Arts Festival (SALA), held on Oct. 29 and 30, welcomed writers and artists alike to examine how the world has categorized them into boxes of different colors, classes and castes on the theme of “shared humanity.”

The program featured South Asian contemporary writers, including Ayad Akhtar, the 2013 Pulitzer Prize winner for Drama who discussed the attempt to define what it means to be American in his latest novel, “Homeland Elegies” and South Asian contemporary artists, including Jaishri Abichandani, a feminist artist and director of the South Asian Creative Collective in New York. SALA also featured South Asian epicurean highlights, poetry readings and a marketplace featuring hands-on activities like henna and rangoli.

These events have been in place since the first SALA festival in 2019. Since then, Art Forum SF, a nonprofit that strives to define and promote the arts emerging from South Asia and its diaspora, has collaborated with organizations like the Stanford Center for South Asia and the UC Berkeley Institute for South Asia Studies. Each year, SALA strives to represent the diverse cultures of South Asia and its diaspora to a broad Bay Area audience.

At the event, artists examined their personal stories wrestling with the rapidly changing policies, social norms and cultural beliefs, offering an open, unadulterated vision for their journey through identity in hour-long discussions that culminated in a 10-15 minute Q&A session at the end. Below are some highlights from the event.

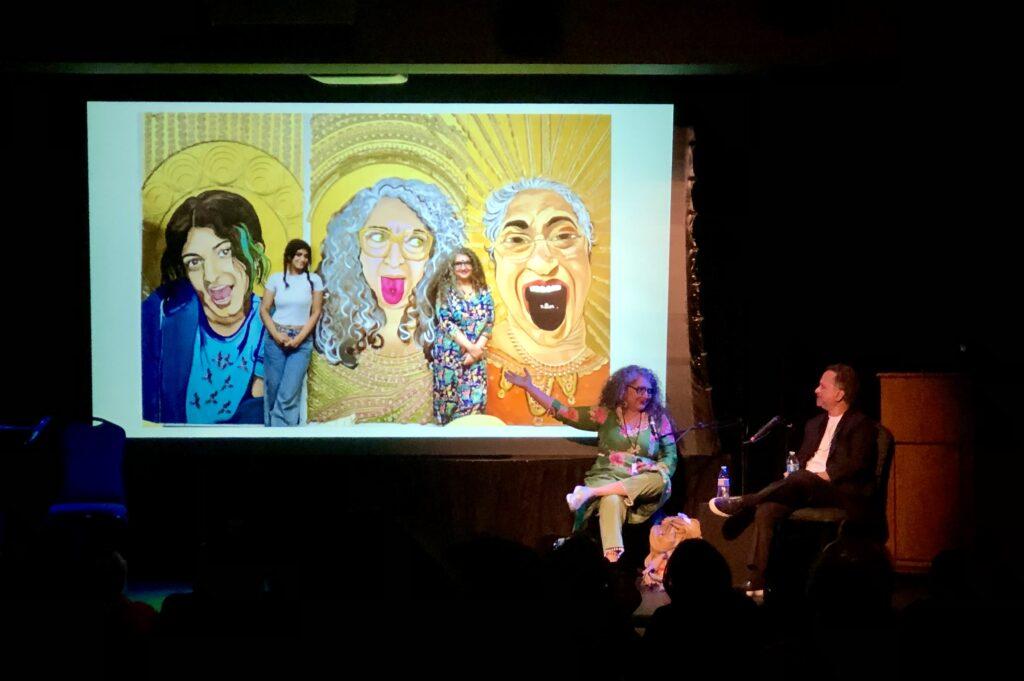

Visual artist Jaishri Abichandani: on portraying the joy of femininity in an iconoclastic society

The vulnerable yet strong image of a female figure sculpted from wood and brass, legs spread wide open, leaning back, with a chimera emerging from her vulva. Feet juxtaposed on delicate, scarlet-red lotus petals. Two spears adorned with various gold trinkets and glass Swarovski crystals, seemingly arranged in the snapshot of the middle of a battle.

Such is what can be found when stepping into the Carriage House, a moderately sized theater at the edge of the Montalvo property. Even projected on a screen 20 feet away, the sculpture “End Game,” created by Jaishri Abichandani, 53, in 2018, was palpable among the audience sitting in rows of theater seats.

The piece wrestles with the motifs commonly found throughout Abichandi’s work — the struggle for autonomy within the constraints of a misogynist Indian family — yet assigns the agency of redefining and transcending such constraints, which originate from old religious beliefs, to the focus of the sculpture: the Sacrificial Mother and the women it represents. This entity, deriving from the notion that mothers are considered to be the most worthy of respect and treated like goddesses in Hindu culture, is metaphorically shown to be engaged in battle with a fire-breathing hybrid, symbolic of delusions, emerging between its legs.

Abichandani, born in Bombay, India, moved to New York City in 1984. Though she was raised in a Hindu household, she later abdicated the religion for its “violent misogyny and caste apartheid,” opting instead to create a new community through artwork that is both reflective of her intersectional feminist identity and, fittingly, demonstrative of a sacred style.

“‘I was born a Hindu but swear not to die as one,’” Abichandi said during the festival, referencing the historic 1956 speech of Bhimrao Ambedkar, an Indian social reformer who had just embraced Buddhism the day before.

That philosophy shows up in many of her works. Abichandani has an affinity for wrestling, challenging and (literally) reshaping the Hindu values she grew up with. Her pieces, particularly her sculptures, exhibit the divine female energy that inspires her creativity through selections of vulnerable yet formidable positions and unapologetic motifs of gold, shimmering blues, and red, vibrant colors that underscore the mutually exclusive nature of a battle for discovering joy in an increasing awareness of society’s shortcomings. She is as much a visual artist as she is a social commentator and feminist.

“End Game” feels as if Abichandani tore her heart open and revealed all her deepest anxieties to the world: the suffocating pressure of a dying planet; the replacement of Hinduism’s caste apartheid with America’s nationalism, and the recurring reminder of perpetuating, misogynistic stereotypes.

Despite that vulnerability, she simultaneously holds the power to compel viewers from across the room — all her jarring interpretations of symbolic figures in Hindu culture, some with limbs detached in commanding positions and others with flowers in place of heads, hold inquisitive narratives that beckon for explanations. Like many of her works, “End Game” illustrates her signature, sacred art style through its reimaginations of iconic tropes in Indian sculptures, which are religious in origin.

Abichandani, while keeping the religious basis in her art, introduces a new element of vulnerability in her choice to express the tension between the constant struggle to reclaim the misogynistic gender norms of society and simultaneously acknowledge the joy that comes with embracing her identity in the scope of current events, mythology and politics.

Even so, joy is a constant across all her works. While all artists have different ways of exhibiting joy in their work, Abichandani makes it her mission to include it in every single one of her pieces while taking note of the sometimes paradoxical nature to depict social issues in such a positive light. Her brave approach directly reflects the bold, unapologetic style of her sculptures.

Happiness is perhaps more clearly visualized through the freedom in her selection of colors, which often revolve around vibrant golds and oranges and the agency she lends to the subjects of her paintings. Even in “End Game,” which exemplifies the struggle for women (the Sacrificial Mother) and the idiosyncratic beliefs of society (the chimera), the subject wields agency over the chimera through its centered position and the concentration of red around her body, representative of sensuality and purity in Hinduism.

The weapons and jewelry depicted on the sculpture are used to adorn Hindu deities in home altars and temples. Combined with the geopolitical allegory taken from the lotus flowers under the Sacrificial Mother’s feet, the adornments exemplify her attempt to quell the violent nationalism that has replaced her religion.

The juxtaposition of natural objects, such as the lotus flowers and the wreath of roses around the Sacrificial Mother’s neck, against the shimmering guild of the golden headpiece and dangling spears, also represent the imperiled existence of human and animal life on Earth due to climate change.

While becoming self-aware of topics like gender-based violence and climate change challenges Abichandani’s means of joyful self-expression, she said the acknowledgment also serves as a “vacuum” that helps her become more aware of her place on the planet and her caste privilege.

“To be born in India is to know that you are superior and inferior to someone,” she told the audience. “[My work challenges that.] My indigenousness is not dependent on any external factors.”

In many ways, creating art in the U.S. is a double-edged sword for her. While the public here is generally uninformed about Hinduism, according to Abichandani, that background has allowed her to create works critiquing Hindu values without much offense. The distance from India has also protected her from the “reprisal and violence by Hindu fascists and government.” Abichandani’s role as a social commentator, then, fittingly aims to establish a new understanding and community around her redefined, secularized interpretation of Hinduism.

In her process of transforming feminist interpretations into means of empowerment while acknowledging the gender and ethnic stereotypes in society, Abichandani said her family played a significant role in encouraging her to keep pursuing the joy that is present in each of her art pieces.

“Balancing personal work and work with my family and community is very important,” she said. “A part of me loves to be in this beloved community and help build it, but there’s also a part of me that is super fragile, vulnerable, emotional and needs to be protected from the energies that I absorb all the time.”

Interacting with the community has helped her deal with the times in her life when there is no moral compass.

“Recently, I’ve been finding it harder and harder to continuously love India for all it’s worth,” Abichandi said, referencing the [Brooklyn] and [genocide.] “However, being able to mess with that iconoclastic culture and reshape it with my own hands gives me a sense of power and joy.”

Dramatist and playwright Ayad Akhtar: absorbing the ‘flow’ of a play through an additional dimension

Before the opening of his show, Pulitzer Prize winner Ayad Akhtar, 52, sits with his Broadway audience and watches the rehearsal. After gauging audience response to his play, he modifies it the next day, rewriting lines and reworking character outlines to transform the experience into a new interpretation that he feels fits the audience’s reactions.

He then repeats the process all over again, each night, for three and a half weeks before the official opening of any of his Broadway works.

This process is, according to Akhtar, the “premium” on ensuring that viewers totally absorb into his work and is one of his favorite parts of playwriting.

“For me, the call and response of the audience is so essential to the experience of creating drama,” he said during the festival. “The movement across opposition is the hallmark of drama — the more there is, the stronger the narrative. As a dramatist, I mainly work in the theatrical form and am very, very attuned to creating an absorbing flow that transports the reader in a way that a good movie would.”

Charismatic and bold, Akhtar finds that the elements he employs in dramatic storytelling for his plays — like the ones in his 2012 play “Disgraced,” which won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Drama — are often intertwined with his other means of writing, such as the techniques used in his newest novel, “Homeland Elegies.”

The novel, inspired by Akhtar’s angst during Donald Trump’s presidency, describes the journey of a family to make a new life in the U.S. and their ties to their homeland of Pakistan. The narrator’s name is also Ayad Akhtar, and like the fact that Akhtar’s father was a successful doctor in the U.S., the father of the narrator is also a doctor — Trump’s fictional heart surgeon prior to his presidency, in fact.

While “Homeland Elegies” is largely a memoir in its deeply personal accounts of identity and belonging in a nation “coming apart at the seams,” Akhtar chose to categorize it as a novel instead, allowing him to have more freedom in expanding the dramatic scope of his own life — in his words, “going for a crazy ride and seeing how far we can go.” By page three, he already found himself changing the facts to make the narrative stronger and sharper.

In the novel, the father represents an “unapologetic embrace and celebration of financial independence and American individuals” while the mother represents a “very, very dyspeptic, anti-colonial, homesick individual.”

While such a plotline was mostly true, Akhtar pushed them further to each side to create more possibility for conflict. Through the role of the novel’s father, who simultaneously loved America and believed that Pakistan was “inherently better,” Akhtar portrayed the themes of half exclusion and half self-exclusion to reflect the narrator’s navigation of the contradiction between society-induced stereotypes and his father’s identity.

While his publicist was “terrified” that the novel would have be rewritten due to legal issues or an unsatisfied customer base, Akhtar and his team was able to push it through after three days.

“[My publicist] was so relieved and said, ‘Wow, you really made up most of this. How’s your dad going to feel about it?’ and I said, ‘well, my dad’s dead. Thank god,’” Akhtar deadpanned. His words were met with a roar of laughter.

It wasn’t the first time a work of his has traversed into tricky territory. Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “Disgraced,” which depicts a successful corporate lawyer who is forced to reconsider why he has camouflaged his Pakistani Muslim heritage for so long, has similarly been criticized for its focus on sensitive topics like Islamophobia. Akhtar recalls a group of scholars who sent out letters warning theaters about the possible “negative ramifications” of the play — ironically, many of those scholars had programmed “Disgraced” for their interpretation of it as a source of diversity outreach.

“My philosophy about producing my work is to do whatever you want with it. If you want to cast it with dogs, fine, I don’t care,” he said. “I mean, the writer who I admire the most and read every day is Shakespeare, and he gets a lot of mileage out of his work, with people programming it any way they want. As far as I’m concerned, if it’s good enough for Shakespare, it’s good enough for me.”

As the president of PEN America, a leading literary nonprofit organization that strives to protect free expression, Akhtar also struggles with separating his role as president from his identity as a playwright. The purpose of art, he said, is totally different from the role of PEN.

For Akhtar, art is not an instance of public speech and artists are not responsible for making communities look or feel better. While he feels that art has been reduced to its advertising and public relations nature, Akhtar said that art should allow its audience to absorb a different order of experience and connect to a “more expansive consciousness,” referencing his psychic visions that often form the basis of his publications.

Since childhood, Akhtar has experienced dreams that he interprets as premonitions. For him, the pain of being a psychic artist involves deciphering dream language through sleepless nights. Through dramatic storytelling and characterization, Akhtar bridges the connection between reality and the dimensional space that he experiences in his dreams — in other words, the “expansiveness” of that other frame in reality that he aspires to have his audience understand.

In “Homeland Elegies,” that “expansive consciousness” lies in navigating the societal stereotypes of America and Pakistan and benefitting from both sides. The narrator, Ayad, is described as a character who is driven by his financial responsibilities and equality of his American and Pakistani Muslim cultures. His desire to make wealth and perception of America in a hopeful, prosper, and abundant light drives the motivation behind his actions navigating such stereotypes.

“Does Ayad [the narrator] hear America singing?” an audience member asked, referencing one of America’s best-loved poems, “I Hear America Singing,” written by 19th-century poet Walt Whitman.

Akhtar laughed. While “Homeland Elegies” is not a purely exuberant celebration about the joy of being American, he said it strives to depict the generational difference that the narrator experiences from perceiving America as a hopeful destination to a country subpar to Pakistan, a viewpoint influenced by his parents.

“In 1961, [former U.S. president John F.] Kennedy asked us all to not think of what the country could do for us, but what can we do for the country,” Akhtar said, referencing Kennedy’s inaugural speech. “Then, there was the idea of America as a place of hope. How in 50 years have we become a country where the dominant political question was ‘what has my country not done for me?’ What an extraordinary movement in how it trapped such a change in sentiment and American hope. My parents came to one country; they died in another. I was born and lived the life to this point in between. Whatever we experienced — us, our generation — we lived through the story of what happened to America. That is the story I’m trying to tell.”