Pacing back and forth and reading their lines aloud to themselves in the quiet of their rooms earlier this month, Sarah Thermond’s Drama 1 students practiced their Shakespearean monologues to perform in front of their class. But rather than the usual in-person performance, this was a presentation done via FlipGrid, a virtual discussion platform that allows students to upload videos to a class assignment.

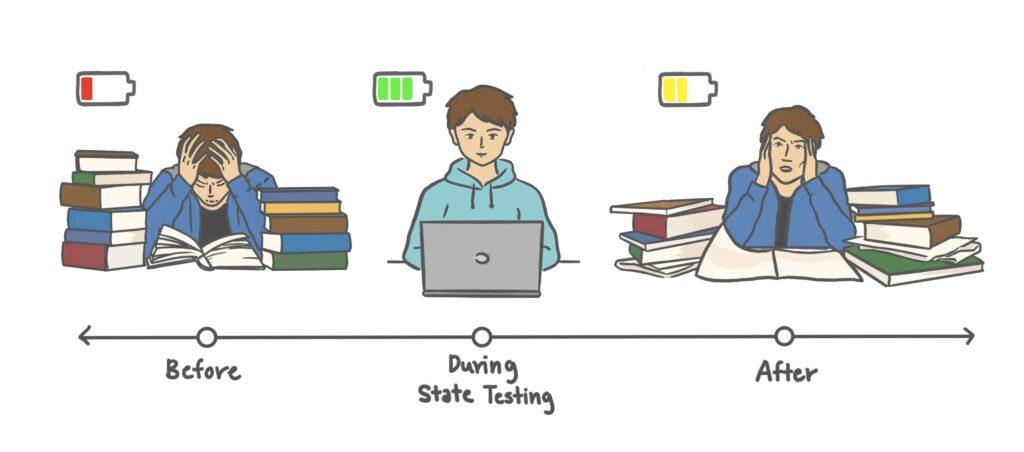

In the wake of the school closure brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, students are adapting to a vastly different learning environment compared to in-person school. Teachers like Thermond are working to keep students’ learning experiences rich and fresh.

For discussion- and performance-heavy classes such as drama, English and history, the shift has been challenging.

For instance, the shelter-in-place order has drastically changed Thermond’s usual methods.

“All levels of drama are normally very collaborative classes,” Thermond said. “My drama classes usually culminate in spring semester by putting on productions in the Drama Center, in which all students have an acting role and a tech job.”

Now she has changed all of the spring productions from a traditional in-theater performance to a virtual, prerecorded one. Students will perform scenes and songs in a recorded Zoom meeting and Thermond will edit the clips into a video to share with the community.

Even though her students cannot complete their regular in-person performances and discussions, Thermond is trying to be positive and emphasize the new skill sets they are building. As such, drama students have gotten the opportunity to undertake new assignments that are more individual or technology-based; the Advanced Drama class learned how to create voiceover reels that could be used to audition for productions outside of school.

“We learned about the different resonating spaces and articulators in Drama 1, so voiceover reels are a great way to show mastery of that,” said junior Helena Lee, one of Thermond’s Advanced Drama students.

Additionally, Thermond has found that she is now able to ensure that all students receive more equal amounts of feedback.

“Because students are submitting things separately on the internet,” Thermond said, “I am able to standardize how much feedback I can give to each student, which doesn't always happen in class as the student performing right before the bell sometimes does not get quite as much feedback.”

History teacher Jerry Sheehy has been following a similar teaching method. For the first three weeks, he conducted all his classes asynchronously and only assigned work on Canvas rather than holding class video calls. This gave his students freedom and flexibility on when they complete their work; however, after learning that remote learning will continue until the end of the year, he has begun holding Zoom meetings so that students can ask him questions.

“Remote teaching and remote learning are challenging,” Sheehy said. “I am learning to do something that is completely new. Generally, everything takes longer, from my planning and conveying instructions to students completing assigned work.”

For his AP European History class, Sheehy is focusing on preparing students for the May 13 AP exam. Because of the recent changes in the exam structure, Sheehy spent much of spring break trying to familiarize himself and his students with the new format.

“We usually watch documentaries and do video guides and we still do that,” said sophomore Catherine Kan. “However, Sheehy now does video notes so it’s like class but shorter so I can finish history faster.”

Similarly, English teacher Susanna Ryan is using a combination of synchronous and asynchronous teaching, keeping in mind that freshman and sophomore classes may struggle with WiFi and other issues that they can’t control. In addition to holding regular class calls, she has made assignments simpler, only keeping the necessary and straightforward questions in worksheets and posting videos of herself walking through instructional slideshows to minimize any confusion that may occur.

In substitution for in-class discussions and group discussions like Socratic seminars, many teachers are also using the breakout rooms feature in Zoom because it allows students to work with their groups rather than with the entire class at once.

Even with a college-level learning management like Canvas and video conferencing tools like Zoom and Google Meet, the new learning environment has led to necessary concessions on the part of teachers.

“It's just too hard for students to follow along with all the nuanced work,” Ryan said. “We have had to really streamline the materials to be both digitally meaningful and properly organized for a student to navigate with only so much direct instruction from me.”

In the midst of the stress and worry brought on by these uncertain times, Ryan said she wants to make sure that her students understand that mental health and personal well-being should be their first priority.

“I want to remember that we aren't just ‘distance learning’ or ‘remote learning’ — we are ‘crisis learning,’ meaning we are all in the midst of a crisis and must put our social and emotional wellness first,” she said.