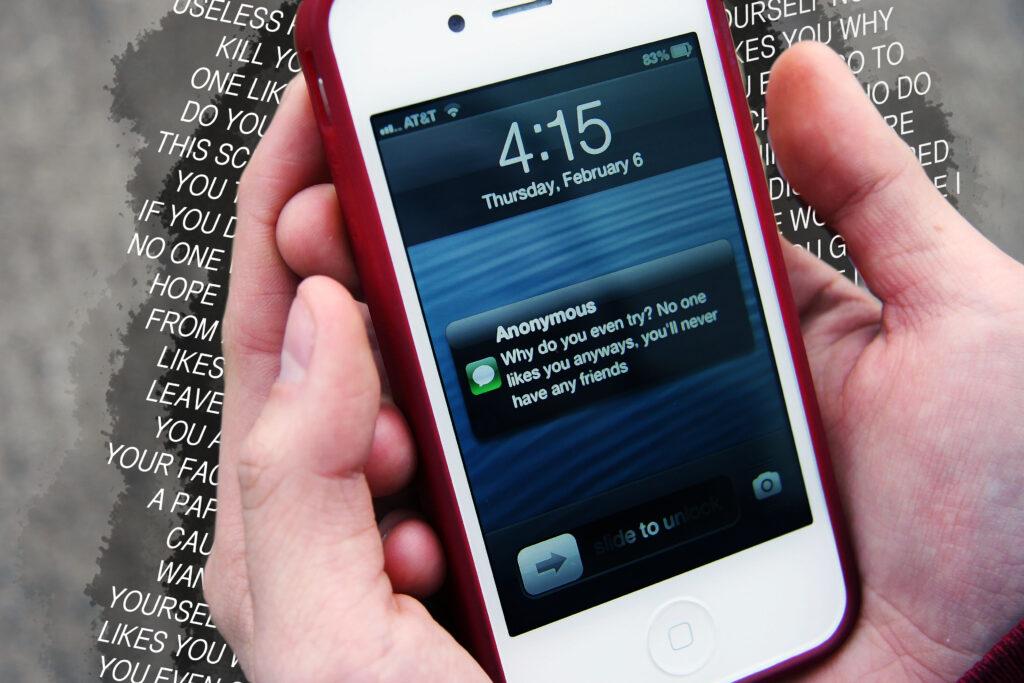

A new California law, Assembly Bill No. 526, that allows schools to punish off-campus bullying, took effect on Jan. 1. School administrators and superintendents can now suspend or even expel a student for bullying that occurs via an “electronic act,” such as sending messages via text, email or social media from an on or off campus location.

The previous law only allowed school suspension or recommendation for expulsion for cyberbullying occurring within a school or directly impacting a school activity or school attendance.

“The safety and well-being of our students is our primary concern. We support changes in the law that support that mission,” district superintendent Bob Mistele said.

Mistele said the district is working with the California School Boards Association to review its policies and to amend them to comply with this new law. Assistant principal Kevin Mount declined to comment on the school’s plan to enforce the law because the school has not discussed the matter yet.

In addition to question about enforcement, an area of controversy surrounding the legislation is infringement on student privacy and freedom of speech. Mistele said the district is expecting court cases and decisions to further clarify this aspect of the new law.

“We certainly support our students’ fundamental First Amendment rights; we also support the right of every student to attend a school where they feel safe,” Mistele said. “[Each cyberbullying incident] will be [considered] on a case-by-case basis, through diligent examination of the facts available, interpretation of the law and, when necessary, input from legal counsel.”

Adam Goldstein, Attorney Advocate of the Student Press Law Center, a nonprofit legal assistance agency headquartered in Arlington, Va., for high school journalists, said the new law does not significantly affect the punishments for cyberbullying, but does change who has the power to do the disciplining.

“The types of speech the law would cover were already unprotected by the First Amendment,” Goldstein said. “Before this law existed, the police could have arrested you for harassment. But now, the school can suspend you for it instead.”

In theory, because the school can still only punish off-campus bullying if it is brought to its attention, the limits of the school’s authority will not change with the new law. Yet, when the bill was first proposed, it gave schools much more power.

“When somebody first proposed this bill, it was supposedly going to allow schools to punish people for saying mean things online. And then someone reminded the author that there is a First Amendment and you can’t really do that,” Goldstein said.

As a result, Goldstein said they “watered down” the bill so that it was legal, at which point it was essentially the same as the previous law.

The version that passed requires that cyberbullying be “serious and pervasive enough” or prevent the victim’s access to education to warrant punishment by the school.

“So if I go online and say, ‘So-and-so who is my classmate is an idiot and the world would be better off without them,’ that’s not enough,” Goldstein said.

That being said, Goldstein said that some schools may end up infringing on students’ First Amendment rights.

“Schools generally work under the assumption that they can do whatever they want whenever they want to. Most administrators don’t know anything about the law,” Goldstein said. “There are going to be schools who are going to use this to try and get more rights than they have.”

Justin W. Patchin, co-director of the Cyberbullying Research Center, said the new law simply reinforces federal law that already allowed schools to discipline students for off-campus behaviors.

“It's uncertain whether anything will change — hopefully increased awareness among educators will help them in responding to cases of cyberbullying,” Patchin said.

According to the Cyberbullying Research Center, California is not the first to pass an off-campus cyberbullying law. In fact, 44 states have school sanctioned bullying laws, 18 of which include cyberbullying and 12 of which include off-campus behaviors.

“More and more [states] are adding clear language that reaffirms the schools authority in responding to off campus behaviors,” Patchin said. “It is still too early to tell if these laws are resulting in any reductions in behaviors.”

Senior Gloria Liou supports the new legislation because she believes it will prevent bullying in the modern technological era.

“A lot of bullying in the past was physical, but now in the modern era, especially in Saratoga, people don’t physically bully each other, it’s all verbal,” Liou said. “And now with the Internet, it is much easier to bully someone [online] because it’s not to face-to-face and you don’t see their reaction.”

Liou added, however, that some people may feel that the law grants the school excessive power since a student’s online activity is outside the school’s domain.

“I guess it kind of infringes on privacy, but you have to consider [that] there are other rights, like right to happiness,” Liou said. “So if someone is destroying the happiness of someone else, you have to weigh which right is more important.”