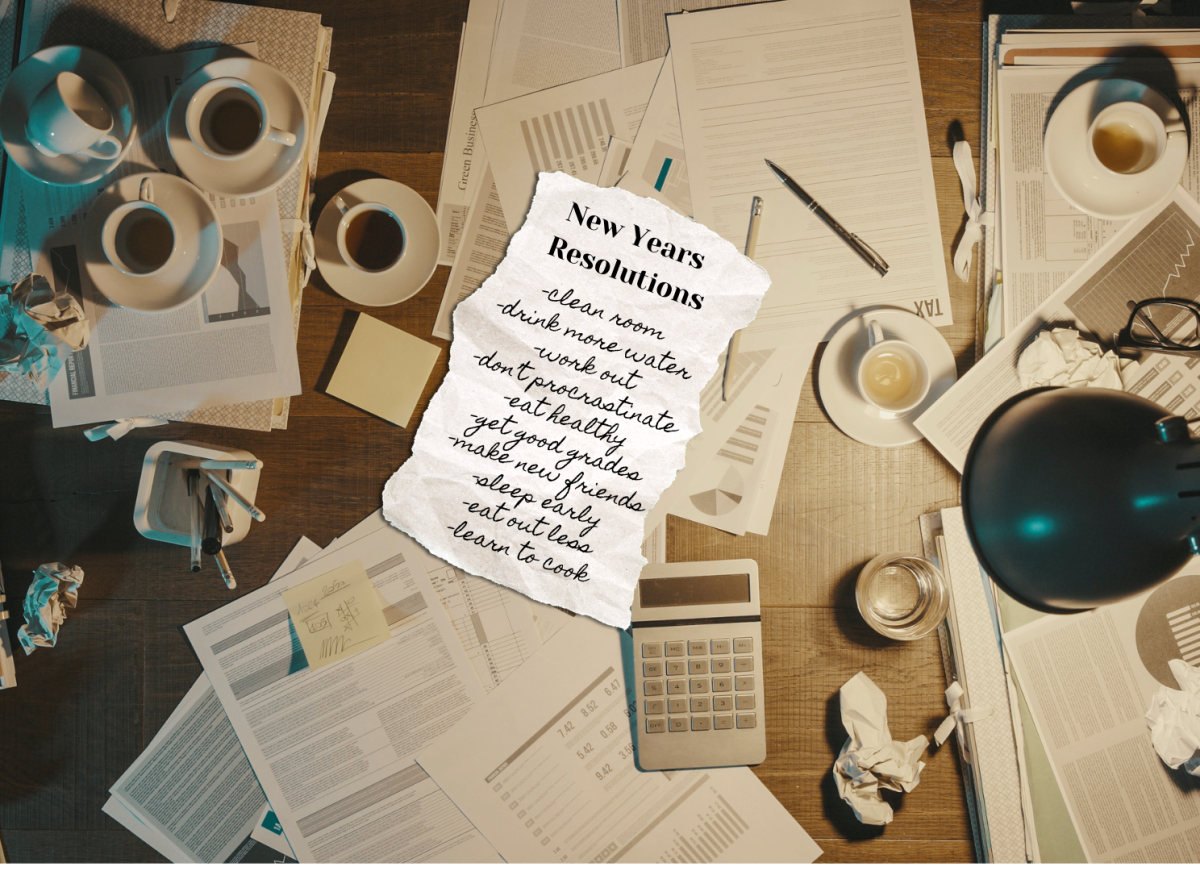

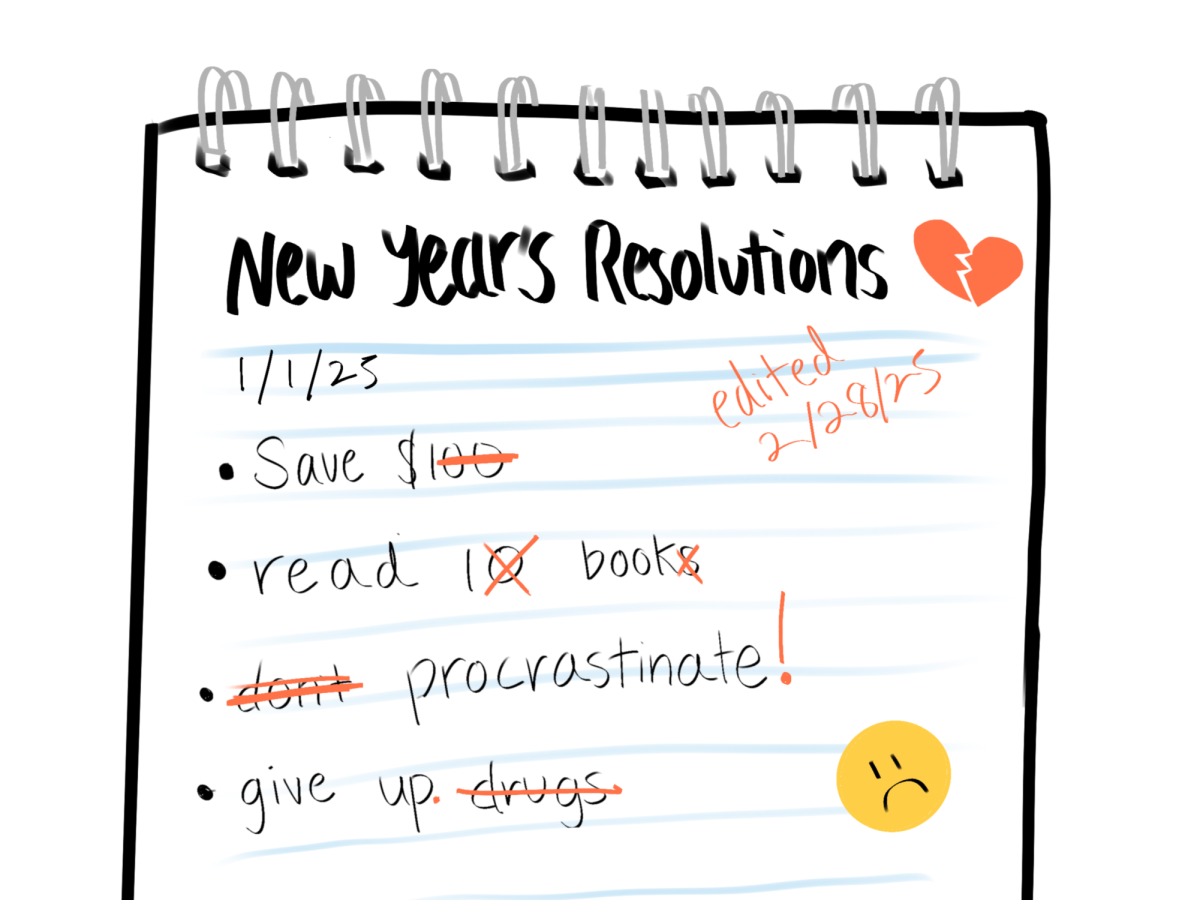

Every year, families and friends gather to greet the new year with a list of ambitious New Year’s resolutions. Maybe your grandpa laughs proudly, saying he’s going to throw out all his cigarettes and quit smoking; your mother plans to go to the gym at the start of every week; and you have promised yourself to stop procrastinating on homework once the spring semester starts.

While these aspirations are always admirable on paper, soon enough, you find a newly bought cigarette pack hiding in the pocket of Grandpa’s golfing shirt; you notice that Mom hasn’t gone to the gym to work out this Monday; and you are already behind on your Chemistry homework packet.

I, too, am guilty of being a New Year resolution traitor. In fact, I don’t think any of my resolutions have lasted for longer than a month, maximum. In fifth grade, it was to read a new book every month — which I promptly forgot about two months later. This year, my unfulfilled resolution was to write journal entries at least once a week — which has ended up being a largely on-and-off process.

Like many others, my hopes were high after making these promises to myself, feeling that — just maybe — this year I would find success. Yet, each time, after a period of fervent determination, I would always end up helplessly straying from my goals. This year, I was journaling consistently from the beginning of the year until the end of winter break. But if you look in my notebook, you’ll notice a nearly a month-and-a-half-long gap between then and my next entry in February.

Interestingly, these resolution-failure-phenomenons happen to most Americans. So if we always fail so many of our goals, what makes us try again on Jan. 1 of every year?

Science explains it with the “Fresh Start Effect,” which suggests people are more likely to experience goal-directed behaviors and increased motivation when they perceive the beginning of a new time period. The reason goals often fail is described with the “False Hope Syndrome,” characterized by unrealistic expectations about the speed, ease and consequences of trying to change yourself. You could even say it’s because your brain’s neural pathways are too used to living like the “old, last year you” instead of the “new you” you’re trying to become.

When we fail to achieve our New Year’s resolutions, it can lead to disappointment and can even cement feelings of helplessness and thoughts like, “It’s not like I can improve anyway.”

Beyond this, what is it with America’s obsession with “new year, new me?” Although the basic idea of New Year’s resolutions is to improve yourself, people shouldn’t have to feel like there is always something they need to fix about themselves. Nobody is perfect, and sometimes, that’s perfectly fine. Instead of pressuring myself to be “better” with unreasonable goals, I’ve learned that I should try to be satisfied with who I am.

Starting this year, I’ve decided it’s better to just escape the cycle of hope, failure and disappointment that comes with the new year. And so, if I had to make one other New Year’s resolution for 2025, it would be to make no more resolutions.