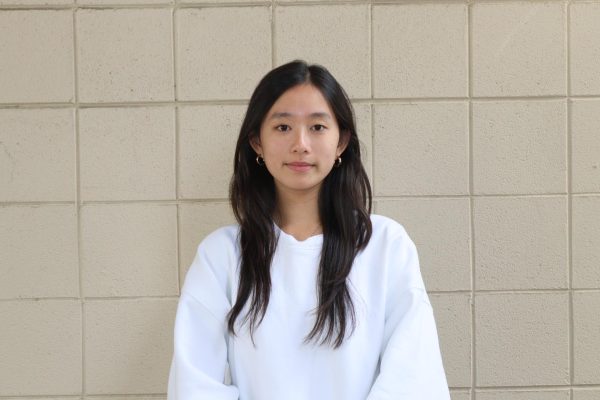

As the final bell rings, the quad is soon filled with hundreds of students rushing to the parking lot, eager to hurry home for an afternoon snack, some phone time or even a well-deserved nap. Freshman Kayley Ren, however, has no time for such indulgences.

Her after-school schedule consists of cramming in homework and shoveling down a nutritious meal before leaving for fencing practice at 6:45 p.m., only returning back home around 9:45 p.m.

When Ren began fencing five years ago at the Academy of Fencing Masters in Campbell, her main hope was to pursue something her mom never had the chance to do

“My mother grew up in Singapore, and there were few opportunities for kids to try out fencing there,” Ren said. “She also prioritized focusing on her academics.”

After two years, Ren decided to move to Silicon Valley Fencing Center for a change in pace.

“I actually stopped fencing entirely during the pandemic,” Ren said. “And when we were allowed to go back, I decided that I wanted to go to another club just to try something new.”

Her fencing skills have improved greatly since she started, and she is now ranked nationally in three categories: 35th out of 141 in Youth 14 (14-years-old and under), 88th out of 120 in Cadet (16 and under) and 111th out of 139 in Junior (19 and under). To earn a national ranking, points are allocated based on placement in national competitions, and points are valid for only one year.

To gain points, fencers must place in the top 32 in competitions with under 160 athletes, or place in the top 64 if there are more than 160 competitors. With such a cutthroat system, every national competition is crucial, as hundreds of young fencers battle for a limited number of ranking points, creating an immense amount of pressure for each athlete as they know that a single slip-up can be costly.

Even with these intense pressures, Ren has managed to rack up enough points to earn high rankings for herself. However, she acknowledges that she still has significant room to grow in the sport, saying, “I’m excited to keep on trying my best and see where it leads me.”

Out of the three fencing weapons — foil, epee and saber — Ren chose foil to specialize in. The foil is arguably the most difficult, as it has the most rules and has only the torso as a target, whereas in epee, the whole body is a target and in saber, the whole upper body is a target. All three of the weapons consist of a flexible steel blade (maximum is 90 cm but depends on fencer’s height), a circular metal disc attached to the blade to protect the hand and a grip to hold and control the weapon with.

For three to four days a week, Ren practices at the club, putting in roughly eight hours there. Each training session lasts two hours and consists of cardio, footwork drills that include retreating movements, lunging and fluid advancement on the strip, as well as practice matches. Additionally, Ren also takes 40-minute private lessons twice a week, but she noted her practice schedule is subject to change as a result of her new more strenuous high school workload.

“I’m pretty worried that balancing my fencing schedule with school will be difficult,” Ren said. “Since fencing and school are two very important things to me, I will have to compromise from time to time and sacrifice one for the other.”

Because fencing involves both physical and mental tactics, Ren admits sometimes feeling defeated by the sport. On the metal strip, the 46 ft x 6 ft playing area marked with a taped center line, two pairs of en garde lines (starting line) and two pairs of warning lines (5 meters from the center line and 2 meters from the end of the strip), they must keep their feet angled in a particular direction, constantly having to bend their knees to a 90-degree angle and crafting a strategy all while closely observing an opponent’s movements and style, waiting for the split second where a tiny opening occurs and striking.

For Ren, though, fencing is mainly a mind game: She said she needs to anticipate the opponent’s next move while simultaneously maintaining precision in her own actions, which makes matches mentally exhausting.

“With all the tactics and rules, fencing can get really complicated sometimes,” Ren said. “I tend to overthink a lot, which makes it difficult to make decisions at crucial moments in the bout (a fencing match).”

However, Ren also believes that the mental demand — although challenging at times — is one of the leading factors that motivates her to continue fencing, even as she enters high school. She enjoys that the sport requires intelligence and consideration behind each action, echoing the quote by Olympic foil medalist Alexander Massialas: “Fencing is essentially a mind game of chess.” Additionally, she admires the tradition and legacy behind the sport’s defining style.

“[Fencing is] very special in the sense that it has been changed and modified, but still has the same key characteristics as older versions of the sport,” Ren said.

With all her hard work and passion in the sport, Ren has created many memorable moments in fencing. Her most unforgettable experiences consist of the competitions that took place just as quarantine restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic lifted for fencing in early 2021.

Most notably, in April of that year, she won second place in a Super Youth Circuit, third place in a Regional Youth Circuit and won a national medal by placing seventh in a North American Cup. Altogether, those three wins allowed her to climb up the regional and national rankings to where she is today. In terms of the future, Ren hopes to continue fencing in college, advancing her education while also improving her athletic skills.

“I feel like fencing has played such a big role in my life, and I hope I can continue creating more memories throughout my fencing journey,” she said.