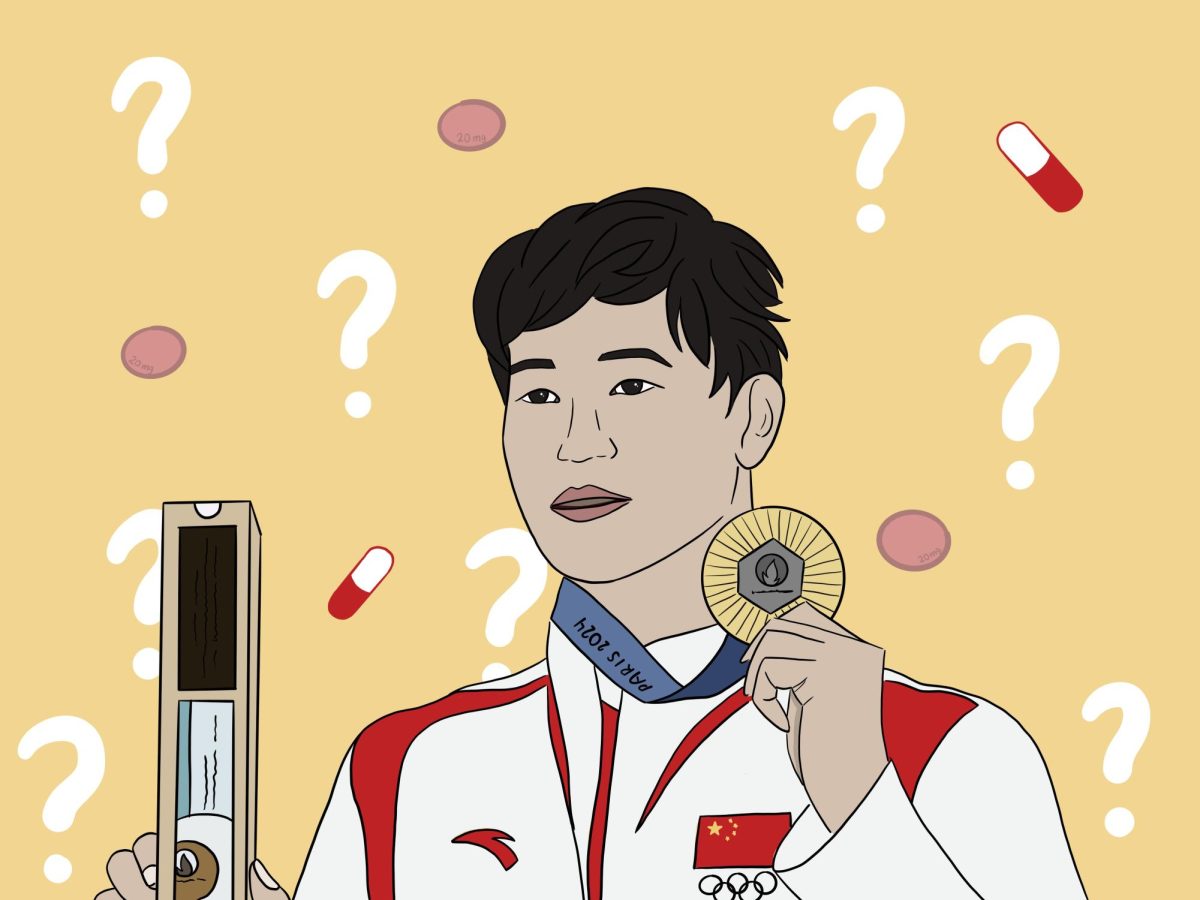

During the Paris Olympics on Aug. 4, the Chinese Men’s 4×100 Meter Medley Relay team clinched the gold medal, breaking America’s 64-year undefeated record. However, the win was accompanied by renewed controversy about the nation’s athletes. A report from The New York Times in April found that 23 Chinese athletes tested positive for TMZ — an illegal, endurance-enhancing drug — ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. These 23 athletes were still cleared to compete after China’s Anti-Doping Agency claimed the chemicals — which were present in low quantities — were in the athlete’s systems due to substance contamination.

Previous Olympic swimming doping scandals have resulted in multi-year bans, such as in the case of decorated Chinese swimmer Sun Yang. The international body Court of Arbitration for Sport dealt him four years in 2020 for refusing to comply with routine drug tests.

Yet, at the 2024 Paris Olympics, 11 athletes with doping records still represented China, raising concerns that previous precedent is being abandoned.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) need to take a stronger stance on doping through longer bans and stricter regulations on governmental doping agencies to set the standard for all athletes. The Olympic Games represent the pinnacle of athleticism and integrity around the globe, but doping creates an uneven playing field, dividing athletes within sports.

Of the 11 athletes who tested positive, this year, two participants — Qin Haiyang and Sun Jiajun — were key members of the gold medal-winning, four-man 4×100 Meter Medley Relay team. Qin, a breaststroke specialist who swept the 50m, 100m and 200m breaststroke records at the 2023 World Aquatics Championships and the 2023 Swimming World Cup, was a favorite to win the breaststroke events at the Olympics. However, his Olympic performance in the 100m breaststroke heat — a 7th place finish over 1.5 seconds behind the first place winner — and his failure to qualify for the finals in the 200m heat, raised questions about the legitimacy of his previous records.

Because of Qin’s positive TMZ test in the 2020 Olympics, his previous clean sweeps in the 2023 World Aquatics Championship and Swimming World Cup should be closely analyzed and tested. Since labs keep frozen blood and urine samples for up to 10 years, WADA should investigate further into athletes whose performance have dropped drastically, such as Qin, and seriously consider removing past medals.

But beyond showing they tried to gain an unfair competitive advantage, the Chinese team’s doping scandal has clouded the team’s reputation, leading to a negative stigma and divide among countries’ swimmers at the Paris Olympics.

For instance, the doping scandal overshadowed Chinese swimmer Pan Zhanle’s world record 100m freestyle. Although Pan had taken over 21 doping tests before arriving in Paris, some critics considered Pan’s record “not humanly possible.” According to various media outlets such as NPR and The Washington Post, the 23 swimmers involved in the doping scandal before the 2020 Tokyo Olympics were a major contributing factor to the skepticism.

The turmoil later soured relations between Pan and swimmers representing other countries in Paris. Following his win, he quickly added fuel to the flame and clapped back at his competitors, alleging Australian swimmer Kyle Chalmers had ignored him and that Jack Alexy, an American swimmer, had splashed water on the Chinese coach. Alongside these comments, Pan said in an interview: “他们看不起我们,” which roughly translates to: “They’re looking down at us.”

The controversy surrounding the Chinese team’s achievements still lingers as debates about the integrity of the Olympics spread to countries beyond China. WADA recently reported that the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) was letting American athletes who had been caught with illegal substances off the hook, although the organization is yet to name specific athletes. WADA stated that at least three serious cases were covered up or dismissed by USADA.

Regardless of country, WADA needs to implement stricter controls over governmental agencies to curb athlete doping. One way this could be fixed is through enforcing longer, or even lifetime bans for repeat offenders. Another possibility would be enhancing oversight of national doping agencies through third-party reviewers, ensuring cover-ups are punished and doping violations are reported promptly.

In this current environment, soft punishments for performance-enhancing drug use lead to a field full of doping violations at the largest athletic stage in the world. Without further regulations, the Olympics could turn into a competition based on deceit, not pure athletic talent.