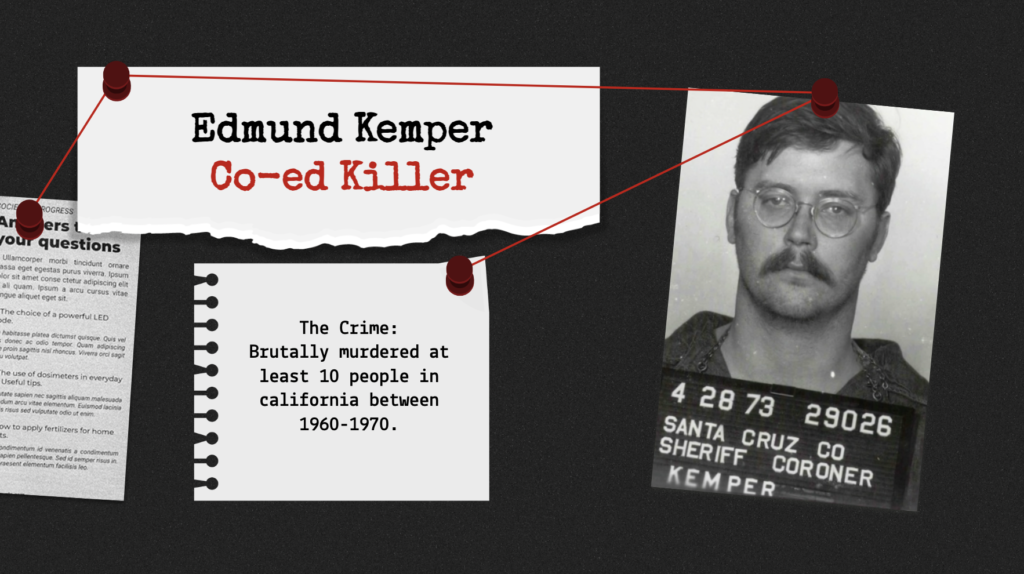

Walking up to the whiteboard, senior president Elsa Fang reads aloud a brief paragraph that sets up a murder mystery featuring serial killer Edmund Kemper, who murdered at least 10 people in California between 1960 and 1970. Fifteen students listen attentively to catch every detail, and fierce discussion soon echoes around the room as they attempt to solve the puzzle.

“I love watching ‘Criminal Minds’ and have been reading Sherlock Holmes since fifth grade, so I decided to create this club,” Fang said.

The Modern Mystery club was created two years ago by Fang, senior vice presidents Zhekai Feng and Carine Chan, senior secretary Isabella Wang and junior treasurer Shawn Wong. With weekly lunch meetings in room 105, the club analyzes evidence and psychological perspectives to find the suspect in unsolved murder cases or online puzzles. For instance, Kemper grew up in an abusive household with an alcoholic mother who verbally abused her husband and ignored Kemper.

Throughout their meetings, the officers include detective puzzles and real-life cases. Cases are selected from connecting online materials to a specific forensic skill or concept. Typically, the officers either make their own puzzles or base them on real-life cases, such as the Zodiac Killer or other past murder cases. The serial killer of the Zodiac Killer case from 1968 to 1969 involved five murders in California, which were never solved. The serial killer was known for leaving bizarre letters and ciphers at each murder scene, but only one was solved out of the five.

After introducing a new case at the beginning of their meetings, the members work together and share ideas to solve the case. Each puzzle takes around 5 to 15 minutes. When the puzzle takes too long to solve, the officers reveal the answer before lunch ends to explain the solution.

“[Our club includes] basically just fun interactive games for students to enjoy,” Fang said.

One of the activities Feng found interesting was finding a spy among the club members. Club members then use clues and camera evidence to determine who the spy is. To make the game more interesting and interactive, the officers replace the people’s names in the puzzle with the member’s names.

“The most fascinating thing about puzzles is the logical reasoning behind it,” Feng said. “I feel like it’s a kind of methodology like in calculus where you have to use existing evidence to come up with a conclusion that is logically satisfying. Solving mysteries might have just started as a hobby, but because of this club, we’re able to share it with anyone who wants to learn.”