Before the tactic even got its name, gerrymandering was already being done: In 1812, politicians changed the boundaries of Massachusetts to favor the Jefferson Democrats, in part leading to a win for the Democrats. This practice continues to this day, and in the modern political climate, gerrymandering is a large part of the American political landscape.

Gerrymandering is deeply problematic and undemocratic. Essentially, instead of drawing competitive districts, politicians choose their voters by drawing a district, essentially a territorial division, with their desired demographic. In doing so, a minority party is able to receive a majority of the votes. This illegal process — though difficult to catch — may occur every 10 years when the voting district is remapped, a policy intended to account for population shifts.

With the new election cycle next year, it is vital that students — some of whom will be able to vote — learn about the effects of gerrymandering. Even though changing the way districts are mapped is out of voters’ control, understanding gerrymandering can allow more awareness about this issue. Election processes have become eroded by partisan interests so much that they are basically rigged, and this affects the voting rights of all communities. If the votes are manipulated to benefit one group, what is the point of putting in your ballot? District mapping should never be used to manipulate vote percentages, nor should it be allowed to alter a majority vote.

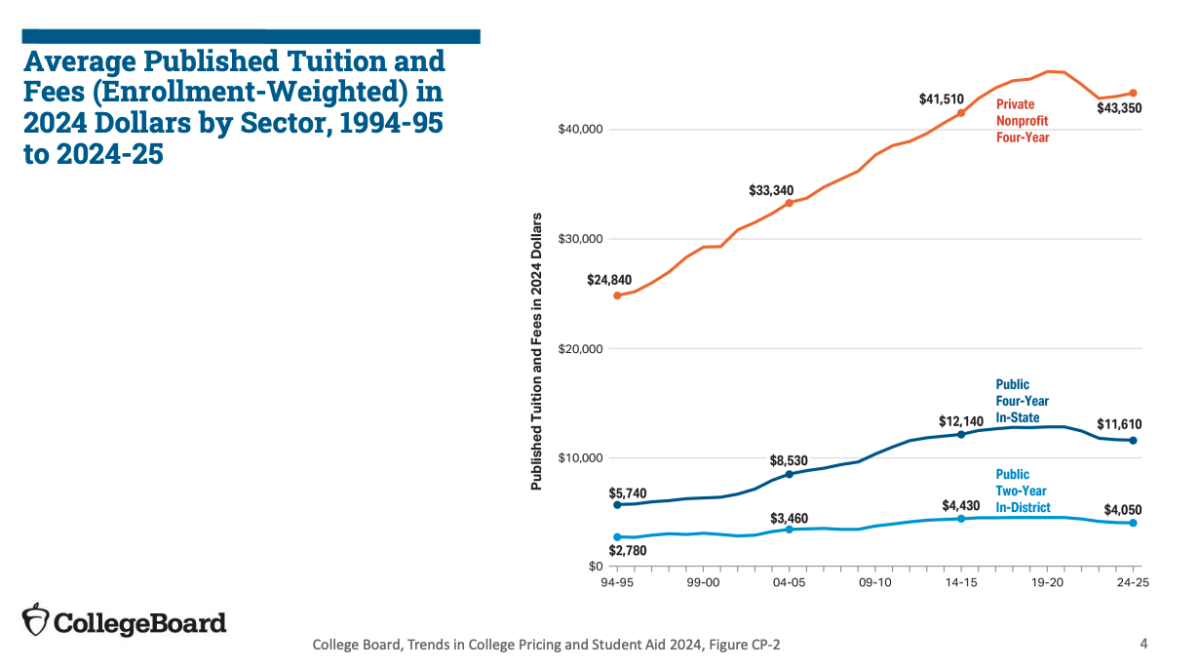

If left unchecked, gerrymandering could have irreversible consequences. In the 2020 presidential election, Republicans attempted to dilute the influence of Democrats in North Carolina before the Supreme Court intervened. According to the Washington Post, if Trump won 50% and Biden won 49%, there would be 10 red seats and just 3 blue seats for the rest of the decade, an outcome completely at odds with North Carolina’s purple (swing state) political division.

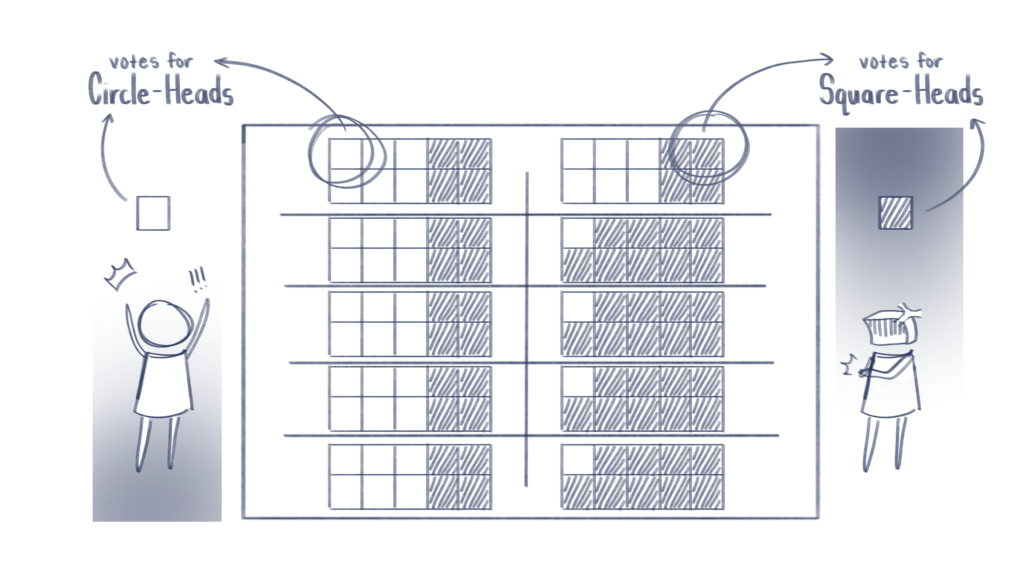

Gerrymandering is done through two main methods: cracking and packing. Cracking is separating a group of people that are under the same political affiliation into different districts, diluting their voting powers.

On the other hand, packing occurs when a group under the same political affiliation is put into the same district. However, this weakens their overall voting strength because those voters have been removed from other districts, making them uncompetitive.

Beyond the effect of gerrymandering on voters, Harvard researchers have found that it disempowers Americans at a district level. Politicians are put in seats, knowing they’re guaranteed to be gerrymandered into office next cycle; thus, they have less incentive to respond to what voters want.

The study also found empirical evidence that gerrymandering illegally dilutes the power of Black voters and other people of color. As a result, these marginalized minorities can’t get their voices heard. One example of gerrymandering, according to the Washington Post, was the 2020 election in Dallas. During the election, there were six competitive areas. Two were leaning Democratic, two were leaning Republican and two were undecided. After the old congressional map was replaced in 2020 and politicians utilized gerrymandering, all six quickly turned into majority-Republican areas.

However, it has been hard to prove that gerrymandering is at work in all cases, especially since district boundaries often don’t look like they’ve been intentionally cut up and tampered with. According to the Brennan Center, cracking and packing usually result in deceiving regularly shaped districts that seem equal but are actually heavily skewed toward a particular party.

According to Reuters, the Supreme Court made decisions in 2019 preventing federal courts from involving themselves in cases involving gerrymandering — a decision which undoubtedly lessened the control citizens have over gerrymandering. While gerrymandering that is considered to be racially motivated has been classified as illegal, partisan gerrymandering has been ruled to be largely OK by the Supreme Court, no matter the distortions and inequities it creates.

A democracy cannot function well with so much gerrymandering going on. Only 10 states in the U.S have fully independent commissioners; the rest are still controlled by partisan interests.

Because election processes are controlled by district remappings, opposing parties fight to skew the district in their favor. Worse yet, when partisan divide and gerrymandering step into the picture, districts are misrepresented, taking away the power of the majority. Voters are crucial for democracy to function, and these rigged maps are not making it any better.

As students, we may not have as much power to directly influence the writing of new legislation. But as soon-to-be-voters, we should educate ourselves to be aware of the existence and dangers of gerrymandering and other issues that affect our democracy, and voice our opinions against it — whether online or in-person.