The first time former assistant football coach Kevin Tanner heard the name Benny Pierce was years before he was in high school. During a fourth-grade Little League game, Tanner collided hard with another player at the plate. As he lay slightly shaken on the ground, he heard his father call at him from the stands, “Get up right now if you ever want to play for Benny Pierce!”

Pierce was the head coach of the Saratoga High football team for 34 years, from the school’s founding in 1959 to his retirement in 1994.

His impact was such that the school named the football field after him. Over the seasons, Pierce led the team into 269 wins, 84 losses and four ties. He had 31 winning seasons, 16 league wins and four CCS championships. When he retired and for several years thereafter, he was the coach with the most CCS wins of all time, according to the Mercury News.

Pierce died of natural causes at 89 on Feb. 11. He is survived by two children and a generation of students, colleagues and friends whose lives he influenced during his time at school and after.

To those who knew him, Pierce was more than a coach — he was a consummate teacher. His legacy is defined not just by a legendary record or a stacked list of accolades and achievements such as CCS victories and powerhouse teams, but by the thousands of lives he touched during his time at the school and after.

Tanner was one of those people.

Tanner, who graduated from SHS in 1981, ended up not just playing football for Pierce, but later working with him as an assistant coach. In his sophomore year, he joined the varsity football team and played as a right defensive tackle for 23 consecutive games until his senior year, where he played both offensive and defensive tackle. He went on to play for Santa Clara University. In 1989, Pierce asked him to be a defensive line coach for the team. Tanner saw the team through the final years of Pierce’s career and for 18 years after that.

“Coach Pierce was truly a special person,” Tanner said. “He was probably the man who most influenced [the person] I ended up becoming.”

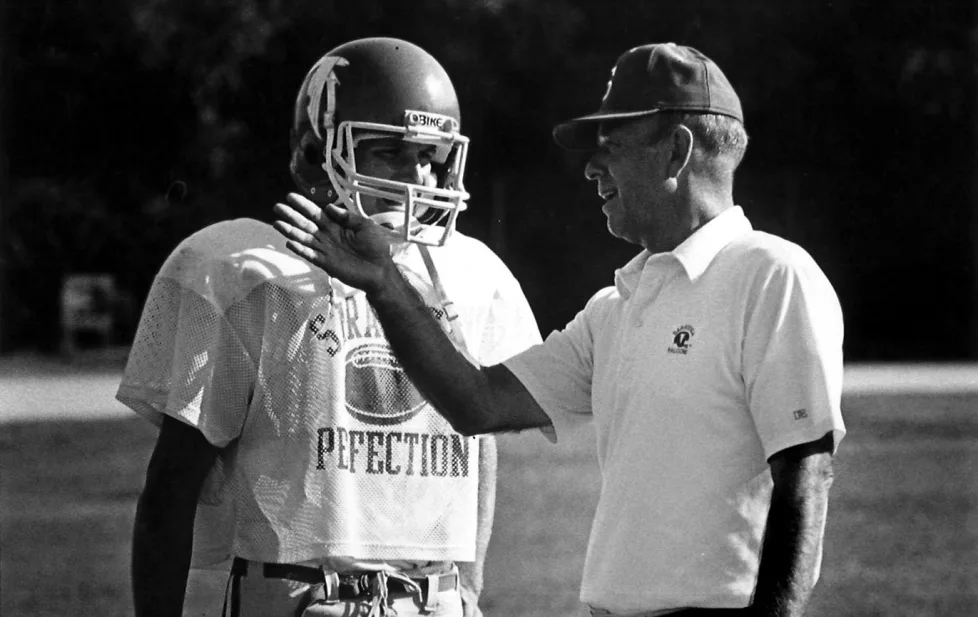

Pierce takes the time to teach one of his players. Talisman archives.

A formidable coaching career

Pierce’s love of football began when at Los Gatos High. A rare four-sport athlete, he earned 12 varsity letters (each commemorating a completed season of a certain sport) in football, basketball, baseball and track by the time he graduated in 1951. His high school football coach, Al Sonntag, was an important influence in Pierce’s decision to become a coach.

Pierce went on to attend San Jose State University and play quarterback on its football team, even throwing passes to a young tight end named Bill Walsh, who would later go on to win three Super Bowls as the coach of the 49ers. He eventually returned to live in Los Gatos and married his high school sweetheart, Mignon Pierce (née Hassler).

In 1959, a small new school opened in the neighboring town of Saratoga. Pierce was soon hired as its first head football coach and a PE teacher.

At its inception, SHS had about 300 students, consisting of only freshmen and sophomores, but soon developed distinguished varsity and JV teams. During his first few seasons, the young Falcons had to be bused to LGHS to play home games because they didn’t have a field. Soon, under Pierce’s leadership and with an abundance of talented athletes, Saratoga began to dominate its league in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Former players said Pierce’s coaching was defined by a pursuit of perfection. He would often run the same play over and over, more than 20 times if necessary, until the players got it right. Whether in the weight room, on the football field or in their lives, Pierce constantly encouraged his players to become “just a little bit better,” Tanner said.

Pierce’s coaching talent was legendary — people often wondered why he didn’t go on to coach college football or join a more competitive high school. The answer to that was simple, according to Tanner.

“He knew he was doing good for other people, and he enjoyed what he did,” Tanner said. “He didn’t see any reason to change that.”

Pierce’s offensive style — a run-heavy Wing T offense — was so iconic that when one of his successors, Tim Tramp, changed the offense during his 2-year stint following Pierce’s retirement, there was a community uproar.

As the team’s demographics changed in the 2010s, former athletic director Tim Lugo, the head coach at the time, was forced to modify the team’s offense to better serve undersized but athletic players who would be less successful at executing run-heavy plays. In 2012, he opted for a version of the pass-heavy Air Raid offense formation. Although it was a smart decision that helped the Falcons beat bigger teams, even then Lugo received flack for diverting from Pierce’s run-focused offense. The experience made one thing clear to Lugo: Benny Pierce’s name and influence were synonymous with Saratoga football.

Lugo first met Pierce when he interviewed for the head coach position in 2008 — Pierce was on the interviewing panel. When he got the job, he said Pierce was always available to help. The retired coach dropped in on games often, and the two men developed a friendship. They often watched Valley Christian football games together (Pierce’s prodigy, Mike Machado, who coached briefly at Saratoga, was a head coach there) and Lugo recalled how Pierce’s “coaching instinct” never went away.

“His mind was always so sharp for the game,” Lugo said. “Watching games with him and hearing him [analyze] plays was an amazing learning experience.”

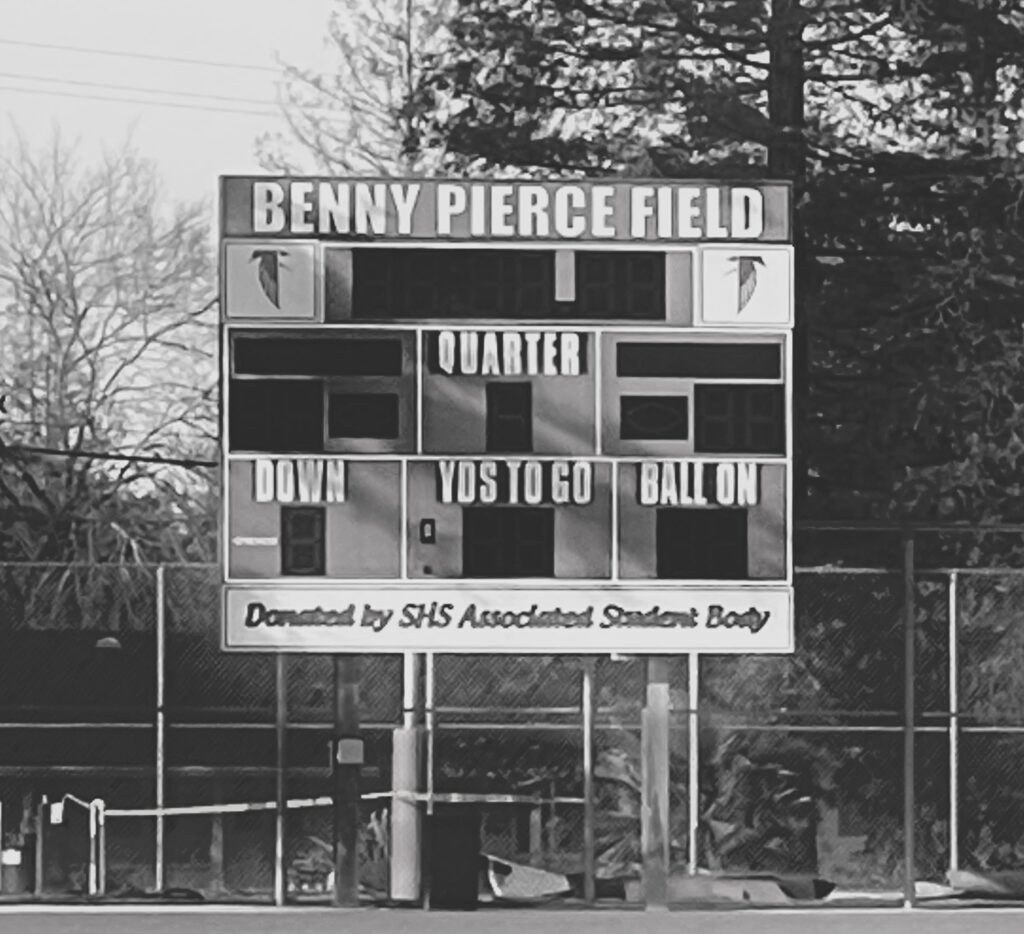

The school’s football field was named in Pierce’s honor in the 1990s.

The lessons for a lifetime

To those who knew him, Pierce was more than just a coach. Tanner said everything he did was a lesson to those around him: To help people become better versions of themselves was integral to his nature.

“He was a kind man with a sense of humor — there was nobody more wholesome than he was,” Tanner said. “He had no vices.”

Karen Hyde, who worked as an assistant principal from 1976 to 2012, said teaching was central to Pierce’s identity. He took it upon himself to impart not just athletic skills but a strong sense of ethics, discipline, respect and pride to each student he coached.

At a time when football teams were notorious for “ill behavior,” Pierce’s no-nonsense attitude and grounded values system kept his players under check. He remained grounded because despite a storied career studded with achievements and a community that placed him on a pedestal, Pierce had an unwavering sense of humility, Hyde said.

She recalled a time when she saw one of the football players running a lap around the field during a game. When she asked him what was going on, the student replied that Pierce made him run laps after he swore on the field — to Pierce, disgracing the uniform with bad behavior was “the sin of the century,” Hyde said.

The closest Pierce ever got to profanity, according to both Hyde and Tanner, was throwing his clipboard on the ground and exclaiming “Fiddlesticks!” when he ran an unsuccessful play. Pierce was a role model for both his students and his colleagues not just in football, but also in morality and integrity.

Pierce remained in touch with his players even decades after they graduated. The close bond he built with them endured throughout the years.

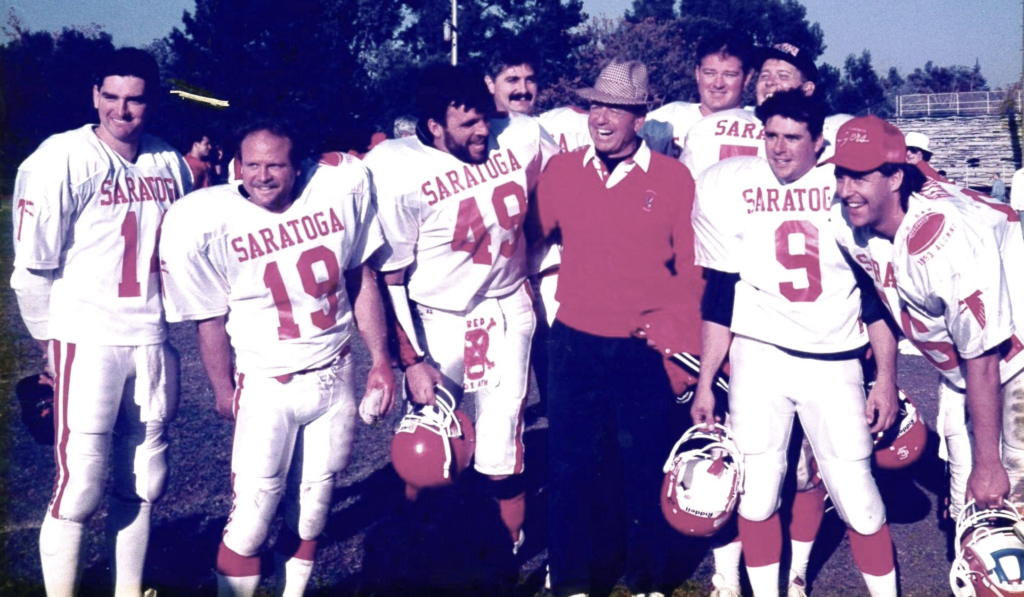

Lugo witnessed this impact firsthand during an alumni football reunion in 2017 at a home game. Along with the players, the 30 or so men gathered in the locker room before the game in anticipation of one of Pierce’s famous pep talks. They eagerly relived their high school football days through excited chants and pregame huddles. When Pierce entered the room, the men’s eyes lit up in reverence in a way Lugo had never seen before.

“The way they looked at him was just different,” Lugo said. “It was like they were 16 again. The love and respect they had for him [seemed to say] that despite being adults and having kids of their own, he was still always their coach. It was the greatest thing I’ve ever seen in coaching.”

Hyde remembers how Pierce’s compassion for his players was exemplified by an interaction with a dyslexic boy on his football team. When given plays to memorize and execute, the player would often confuse his left and right side and execute the plays incorrectly. When Pierce realized what the problem was, he marked “L” and “R” on the student’s left and right shoe to help him reorient himself after each play. He also began changing his calls to make it easier for him to understand.

“He taught thousands of kids over the years, and they all came away with the same things: Be true to yourself, honor those around you, always strive to be a better version of yourself,” Hyde said. “There are so many people who would walk on fire to help him because of what he did for them.”

Pierce’s legacy

Today, whenever crowds turn their eyes toward the scoreboard during home games, they see Benny Pierce Field proudly emblazoned. SHS has only had a true football field complex since 2013, though the team stopped playing games at Helm Field at Los Gatos years earlier.

The pristine stadium and turf field stand upon what used to be a simple grass practice field with a rickety bleacher on each side. This grassy expanse was where Pierce ran thousands of drills for the entirety of his career, preparing his players for home games at Helm Field in Los Gatos.

Building the new stadium complex and field was a labor of love for Tanner, who took it upon himself to design, fundraise and organize the construction of the project. It was a way to commemorate Pierce’s monumental impact on generations of students.

But apart from the name on the field, Tanner believes there “isn’t much left of [Pierce]” at Saratoga. This isn’t a good or bad thing, he said, but a consequence of the passage of time and decades of change since Pierce left. Rather than commemorations and tributes, Tanner thinks Pierce’s legacy is most preserved in those who knew him, loved him and felt his presence transform their lives.

“The truth is that if you never played for him or knew him, you can’t feel his influence,” Tanner said. “I don’t think it’s possible for people who didn’t know him to understand just how much he mattered to so many of us.”

Pierce’s family and friends have planned a celebration of life on March 25 at Venture Christian Church in Los Gatos. Tanner, Hyde and Lugo will all be in attendance, along with hundreds of others. Many are flying in from out of town for the occasion.

Tanner said that following the service at the church, many ex-players will meet for a reception afterwards at “the field.” He did not mean Pierce Field but rather Helm Field, where alumni shared many of their most precious moments together at home games before Saratoga had a field of its own.

Hyde recalls a flurry of messages and voicemails from many alumni in the days following Pierce’s death. There were people who had not seen her in decades suddenly reaching out, desperate to find out information about the memorial. Many of the emails were signed off with “Red pride forever,” a saying that originated during Pierce’s time — he kept the team in red and white uniforms despite the school’s official colors being scarlet, gray and navy blue. Hyde plans to wear red to the memorial service, and she speculates that many others will as well.

“Coach Pierce was a mentor, a true teacher,” Hyde said. “Somebody who climbs inside your head and heart and makes a difference. He turned average into remarkable, and we were all the best versions of ourselves around him. There is nobody in the world who can replace who he was.”