Tech funding is a challenge that schools across the nation have wrestled with for years and SHS is no exception. Even the funds raised from the district, the SHS Foundation and other sources haven’t been enough to meet the growing needs.

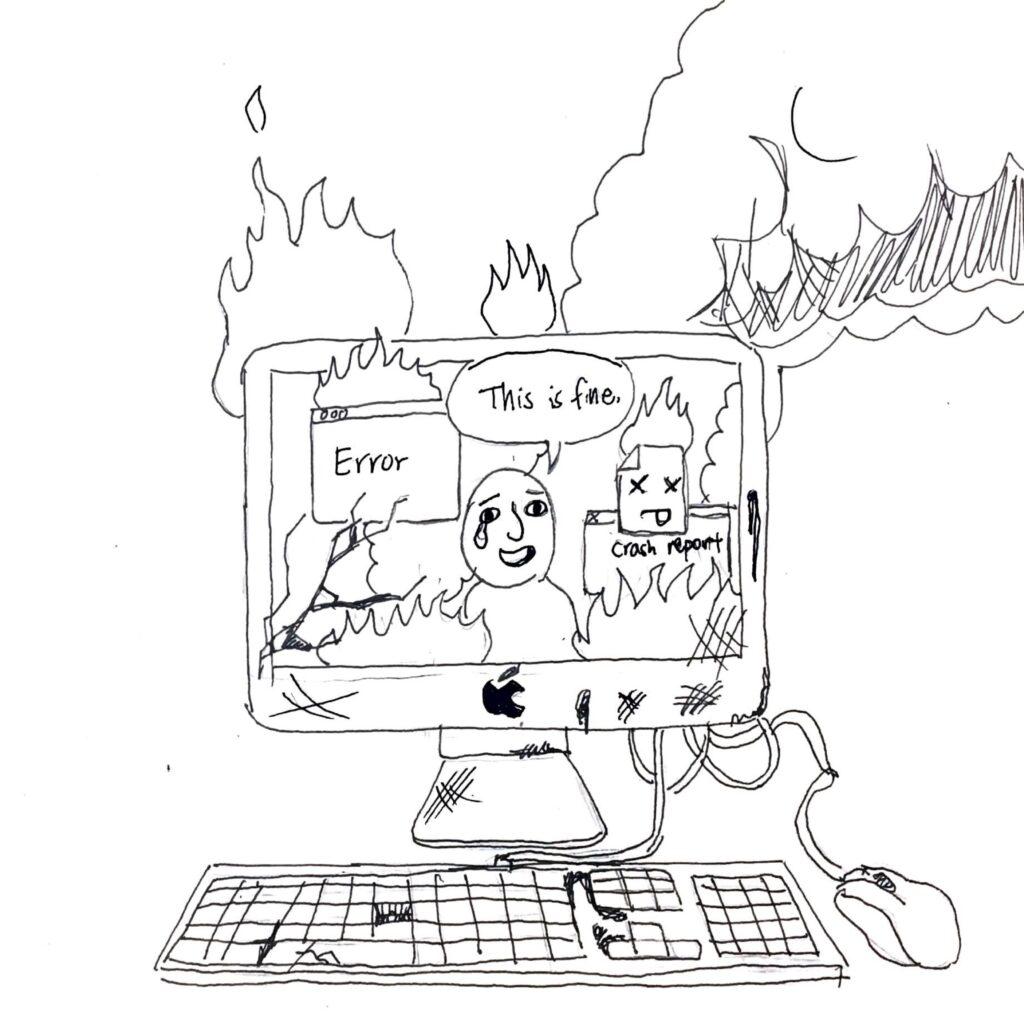

Students have returned to campus with aging desktops and Chromebooks ranging from 2 to 8 years old for use in labs and classrooms — and the district technology department, composed of a mere 4.5 members, has weathered students’ frustration and concerns.

One example: In classes like newspaper and yearbook, where the effectiveness of Adobe programs used to design layouts is dependent on the hard drives of existing technology, entire electives are at stake: If these computers are hanging on their last thread, so are the classes.

The current iMacs in the journalism room, for example, are 2013 models. Developments since then, such as faster, 18-core CPUs and updated ventilation systems in iMac Pros, satisfy speed requirements for Adobe software. Without them, Adobe software cannot reliably be run on 2013 iMac computers.

Combined with some 350 students from the entire Media Arts Program, which also heavily relies on Adobe software, these classes impact 470 students — nearly 40% of the school’s population.

While the technology department actively reviews applications for new technology and technology replacements, such changes consume tens of thousands of dollars at a time: Refreshing all 33 of the J-room computers will likely cost upwards of $55,000, according to Julie Grenier, the district’s director of educational technology.

For an aspect of daily life that has arguably had the greatest impact on students this past year over the pandemic, technology should be a key priority. But even so, funds are limited and the school district can’t refresh all classrooms at the same time — that would cost millions of dollars. So where can the school allocate the necessary funds to refresh technology?

In recent years, students have been encouraged to bring their own devices to school for classes. Admittedly, this does save money, but not every student can or will be able to bring an acceptable device.

Outside the current scope of the school, seeking donations from alumni is another possible way to get more tech funding. According to US News, alumni donations at U.S. colleges alone totaled more than $11 billion in 2019.

Along with measures to cut costs or seek funding from outside sources — be it alumni, big tech companies or residents — it would be smart for the school to have a booster organization dedicated only to tech funding.

The school already has over 10 booster organizations set up for programs such as MAP, speech and debate and MSET robotics. Even the two main foundations, the SHS Foundation (SHSF) and the PTSO, are dedicated to general school and on-campus facilities and needs, though they have funded tech efforts in the past.

The problem with this method is consistency: How often will the Foundation be able to cover big-ticket items such as a $55,000 lab in multiple classes?

The percentage of funds that SHSF spends on technology “varies greatly from 20% to 50%” depending on the school’s needs, according to SHSF President Tom Coburn. For example, a good portion of the funds last year went towards buying new furniture for 10 classrooms instead.

A tech-focused booster organization could fund additional (and important) tech employees and focus on raising money for everything from iPads in math classes to Chromebook carts in science classes.

Tech companies’ community outreach programs should also serve as a major source of support for a tech boosters group. In addition to funds from students and parents, the booster organization could also reach out to companies like FAANG on behalf of Saratogan employees, which could land relatively up-to-date technology and simultaneously help recycle equipment that would otherwise end up in landfills.

Historically, collecting adequate funding for refreshing outdated technology in schools has been a struggle. In 2011, the state gutted education funds as population declined, an issue that has progressively been getting worse since the pandemic.

Despite the $1.69 million annual loss in funding for the district at the start of the pandemic, the district tech department was able to issue Chromebooks for students during quarantine, and nearly every staff member received a new laptop in addition to other necessary equipment such as document cameras to weather the change to online teaching. Funds were also directed toward upgrading wireless infrastructure in 2020, which include rooftop wireless sites and other facilities that transmit wireless communications, thereby providing more access points for students when they returned on campus.

Changes like these are often happening without students even realizing it: Beyond updating computers, the school also has to fund for hardware like projection systems, AV (audiovisual) systems, printer maintenance and software systems like Canvas and Google licensing for students. A tech booster organization could only help with these enormous expenses.

Compared to the level of technology used in classrooms in the 1970s, the nature of education today is worlds apart. Within 50 years, technology has gone from low-level equipment such as typewriters for the sole purpose of writing and $1,700 iMacs with 4 GB storage and floppy disks to current-day laptops with 4,000 GB storage and convenient, immediate access to information and software applications that classes like digital animation and media arts revolve around.

But though these advancements have a transformative impact on education, they also pose a daunting challenge for schools that need to keep them up to date and in good working order.

With the huge role of technology in the school today, more should be done to maintain it, and a dedicated booster organization is a good place to start.