At 2 in the morning on Saturday, March 27, I sat at the dining table with my mom, craft supplies scattered all around us.

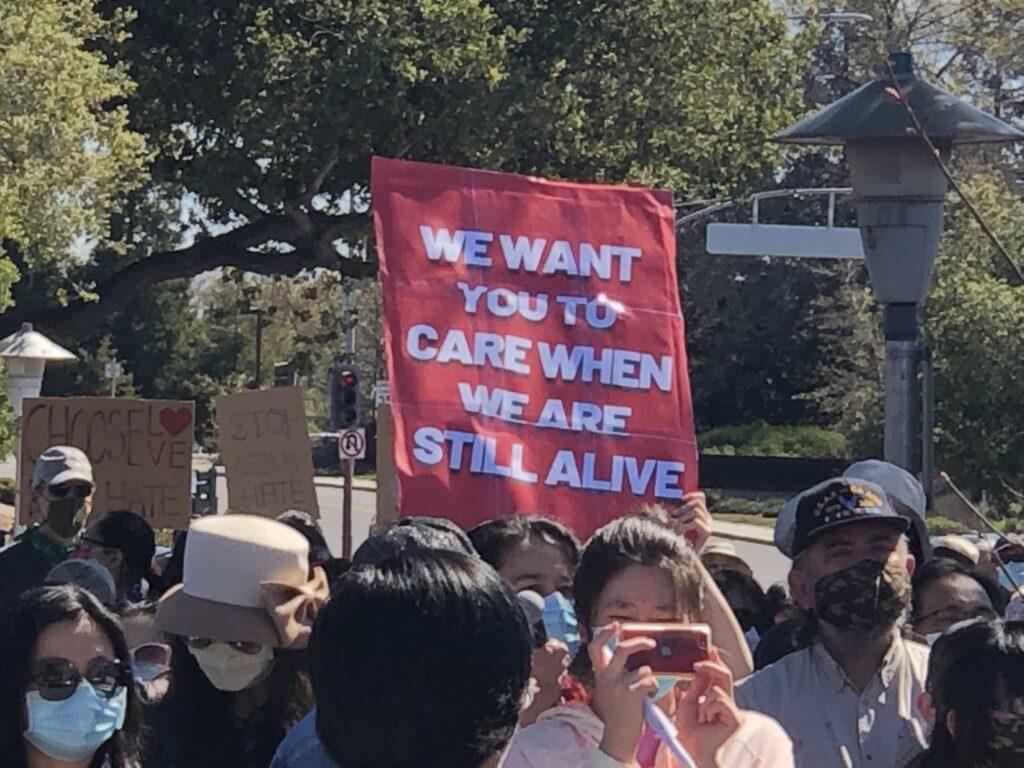

An anti-hate rally was scheduled for later in the morning and we still had dozens of signs left to make. Besides the scratch of permanent markers on cardboard, we worked in silence. I watched her tired but determined face as she finished one poster and pulled out another, printing clearly a message in dark blue sharpie.

“We Are Not Your Model Minority,” the message read.

The past few weeks have been a painful time for the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. For hundreds of years, we have seen our stories cast aside, with the discrimination against us disregarded and our voices as a political constituency ignored.

However, the recent rise in visible hate incidents against us and attention brought to them by the media, while saddening, has served as a rallying point for our diverse and often infighting community.

And when we are united, real and lasting change is possible: in shifting the perception of our community in the media, in changing public policy and in supporting and understanding our own community.

I never expected there would be a day like this. Just a few months ago, during the rallies and protests for Black Lives Matter, it wouldn’t have been out of the ordinary for me to hear Asian American adults and some peers assert that racism doesn’t have any effect in modern American society. Or, they would say to ignore it, considering our Asian American community too different from the Black community to relate to their demands for change.

It’s a proud and individualistic sentiment — if law-abiding Asian Americans could toil and climb to success in American society, then other races should be able to as well, an uncle would say, watching news channels broadcast the lootings and riots of June 2020.

“Protest is for those who don’t want to earn respect the hard way,” he would say.

This transient feeling of superiority, the belief that Asian Americans have somehow risen above racial discrimination through being model citizens, shatters under the realization that we are only accepted as long as it is convenient — something that has been made clear in recent weeks with the massive influx of reported hate incidents against Asian Americans.

A shooting in Atlanta on March 16 killed eight people and six Asian women. Attacks and hate incidents against Asian men and women, particularly the elderly, are being reported at unprecedented levels. It has been mere months since the end of the term of a president who constantly ridiculed and blamed China for the coronavirus, then referred to the virus itself repeatedly with pejoratives like “Kung-flu” and “China Virus,” enabling reproach toward Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans.

The Asian American way has always been quiet acceptance of the reality of discrimination against us and an attempt to raise ourselves above it without stirring trouble. It is a survival strategy that has been fine-tuned after years of discrimination, from outright exclusion to microaggressions. An attitude of “I made it, so why can’t you” is rampant in Asian American communities like ours, where our skilled immigrant parents have essentially achieved the American Dream in material terms.

The issue is that we in communities like Saratoga represent a small and exceptionally privileged sector of the Asian American community. While our parents have undoubtedly worked hard to achieve a high quality of life, the reality is that many Asian Americans live in difficult circumstances.

These AAPI, often living in close-knit ethnic communities in cities and working low-wage jobs and positions just like the Asian women massacred at the massage parlors in Atlanta, often face little to no social mobility and similar issues to Black and Latino communities despite being burdened by the reputation of the model minority. It marks them as immigrant opportunity thieves and leaves them vulnerable scapegoats for a population angered by a year of pandemic restrictions, economic volatility and violence.

These less-privileged communities must constantly face struggles that we have the privilege of distancing ourselves from: living in dilapidated areas prone to violence from people looking for someone to blame, working in cultural businesses like markets, stores and parlors that are an easy and vulnerable target, and in some cases, even failing to report hate incidents that have happened to them.

A recent survey from AAPI Data found that while roughly 1 in 10 Asian Americans had experienced hate crimes or hate incidents so far this year, Asian Americans are the least likely racial demographic to report hate crimes, likely due to fear of retaliation, concern over whether justice will actually be served, or a cultural mindset of beating unfairness by just working harder.

In the Asian American community, there is a great disparity in opinion on the existence and perpetuation of racism both generationally and across different backgrounds and ethnicities. However, recent incidents have made it clear across generational and cultural boundaries that discrimination and hate against Asian Americans still very much exist, just less visibly for those who are protected by privilege. And as can be seen from the rise in solidarity and support across all AAPI communities, Asian Americans are beginning to realize that the issue persists regardless of socioeconomic status — achieving enough material success doesn’t make racist attitudes go away.

Anti-Asian discrimination is not a new phenomenon in America, having been projected in gradually more subtle ways for centuries. While the pandemic has brought the tensions against Asian Americans to a head and resulted in saddening incidents and violence, we as a community now have the opportunity to take a clear and united stand — across generations and circumstances — against violence and racism.

Once we are united in the pursuit of a common goal with the support of other POC communities, we will have a social and political voice to harness. We will no longer be silent.