During the weeks leading up to the Nov. 3 presidential election, it wasn’t uncommon to see students repost graphics denouncing their friendships with people of the opposing political party. Also during this time, the media became consumed with stories such as 50 cent and Lil Wayne’s rift over politics and Claudia Conway’s emancipation from her mom, former Trump administration senior advisor Kellyanne Conway.

If there has been any time where the media was most reflective of the United States’ political atmosphere, it is now. According to a May 2020 study by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, “Polarization recently reached an all-time high in the US.”

This polarization has manifested in the growing politicization of the news outlets and most infamously — friendship — or even family — break-ups. Like the name suggests, a political friendship break-up takes place when two people end their friendship over a difference of political opinion.

With “political” friendship breakups becoming increasingly common, the popular question has now become whether these breakups are justified.

To answer this question, I always think back to the famous James Baldwin quote: "We can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist."

In this quote, Baldwin says, ultimately, disagreements — whether casual or political — in friendships can be tolerated, unless they fall into the category of human rights discourse.

But what’s the difference between political and human rights discourse?

Political discourse refers to disagreements over topics — like the allocation of tax money — that don’t affect whether or not a certain group is given equal provisions under the law. On the other hand, human rights discourse refers to disagreements over topics that directly impact whether a certain group will receive the same treatment under the law as their counterparts.

The main problem has been that under our current political climate, human rights issues have been far too commonly conflated with partisan issues, a good example of this phenomenon being our nation’s adoption of marriage equality as a strictly Democratic cause.

Although some may argue that marriage equality is a Democratic agenda item, it’s important to revisit the original meaning of the term human rights. According to the United Nations, a human rights issue refers to any type of issue that would infringe on “the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education.”

This definition simply places marriage equality as a human rights issue — regardless of religious belief.

Returning to the question of political friendship breakups, I quoted the word every time because the reasons for most so-called political friendship breakups are rarely due to actual political discourse. In fact, every time I hear about a political friendship breakup, the basis of division almost always has to do with disagreements over basic human rights issues (reproductive healthcare rights, LGBTQ+ marriage equality, migrant border detainment). Rarely have I seen anyone end a friendship over purely political issues that don’t involve human rights like an economic plan or government technological restrictions.

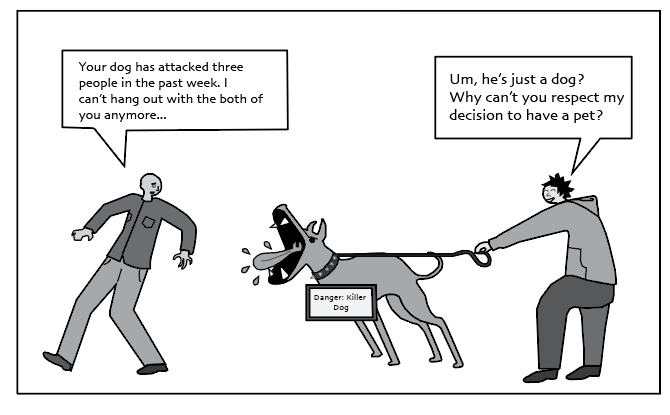

And this makes sense, because regardless of how amicable two people’s face-to-face interactions may be, the dynamic immediately becomes uncomfortable and emotionally harmful if one person is advocating for the other’s oppression or the repeal of the other’s rights.

As a woman, I cannot imagine myself being comfortable around someone who believes that women should not have access to reproductive healthcare. For me and many women across the country, needing access to reproductive healthcare isn’t a matter of “political opinion” — it’s a basic human need that has proven to inflict death and physical damage when not met.

Additionally, naming oppressive opinions political opinions is just an excuse for forcing people — especially marginalized peoples — to tolerate opinions and policies that are inflicting damage upon their communities. (Think, for example, of the mid 2000’s “Anti-Racist Is a Code for Anti-White” movement that called anti-racist movements intolerant for refusing to pander towards a white nationalist audience).

So instead of oversimplifying these friendship breakups by naming them as purely political and antagonizing that oversimplification, it’s important to understand the reasons for those splits. In some cases, it has to do with one person essentially supporting policies that would fundamentally damage another person.