Three years ago, my eye doctor of many years retired, and his replacement was a young Indian woman who I thought was just as gentle and efficient as her predecessor. She introduced herself to my parents and gave them information on my eyesight; my dad smiled and talked with her kindly while my mother stood a little to the side.

When we were eating dinner that day, my mother said she wanted me to go to a different eye doctor. “She’s Indian,” my mother said. “Maybe we shouldn’t trust her.”

My brother and I both thought this was entirely unreasonable. My dad also disagreed, but he hesitated a little before voicing it. I couldn’t understand what my mother didn’t trust — I had been classmates with Indian people since preschool, and I had never thought of them as anything less than me.

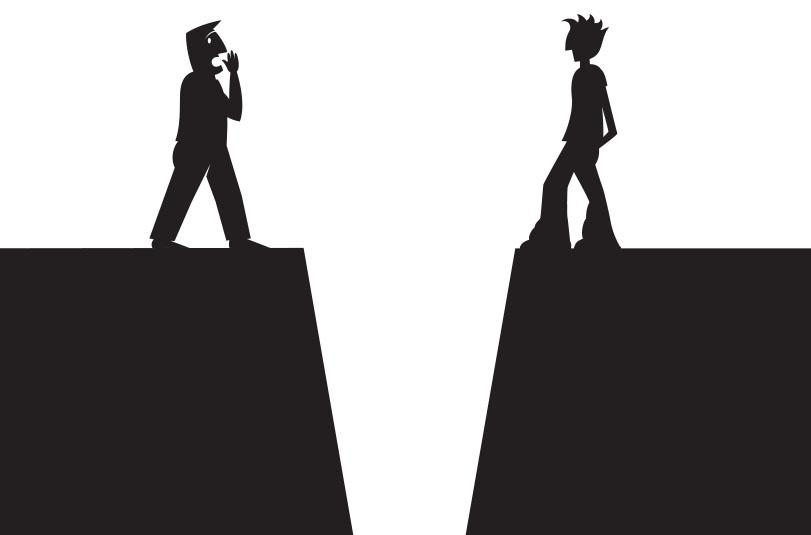

But then, I realized a few days later, perhaps that was the reason that I didn’t feel differently toward Indians. My brother and I had grown up with them, but my parents had probably never seen an Indian person before moving to the United States in their early 20s from China.

Of course, my mother’s background doesn’t (and never will) excuse her blatant racism, but our different childhood experiences suggest why my brother and I hold such different values than our parents do.

My generation has grown up in the “melting pot” of the U.S., giving us exposure to a variety of ethnic groups and cultural backgrounds. According to the Los Angeles Times, racial minorities now comprise roughly half of the students in the nation’s K-12 schools. Here in Saratoga, where the majority is minority, I’ve been surrounded by second-generation immigrants from South Asia, East Asia and Europe, among other regions.

As a result, I’ve grown up accepting others’ cultures, which is an advantage that second-generation immigrants hold over certain first-generation immigrants. I spent my childhood with second-generation Indian immigrants, laughing and learning alongside them; there’s no reason that I would ever think of them as untrustworthy just because of their ancestry.

Yet my refusal to blindly accept my mother’s beliefs can be attributed to natural childhood tendencies as well, not just a change in cultural environment.

According to a study by Kristin Lagatutta, American children aged 4, 5 and 7 believed that a child protagonist of a novel would defy their parents if their parents infringed on their personal choices, such as by dictating what the child should or should not wear. Similar results were concluded in another study by Matthew Gingo on children aged 8 to 12 — although children were willing to comply with authority when it came to safety and health, they were much more likely to reject authority interfering with their beliefs on morality or social behavior.

This trend is reflected across cultures as well. In 2014, Judith Smetana compared American children to their counterparts in Hong Kong, and her study revealed that children in both countries were less likely to bend to rules regarding personal choices.

Although my initial opposition to my mother’s racism was likely because I grew up in the U.S., my continued rejection of her values resulted in part to inherent rebellious tendencies.

My mother also maintains several sexist ideals that I assume come from her Chinese background. She constantly tells me to take care of my skin and eat certain foods in order to brush up my appearance, and I’m positive that her ultimate goal is making me look desirable for a future spouse. She rarely berates my brother for the same things, and when she does, it’s usually as an offhand comment after she has already scolded me.

Her view of the role of young women in society was most likely passed on to her by her parents. Chinese culture is significantly more conservative than American culture is, and the idea of young women being objects of beauty for men is still widely perpetuated by Chinese and other Asian entertainment industries.

But growing up in the U.S., I’ve become resentful of the idea that a woman serves the sole purpose of impressing a man for marriage. Women in America are encouraged to develop their own identities and act in a way that makes themselves feel confident, and as I become less afraid of defying my mother, I find myself developing the same mindset.

Don’t get me wrong, though. Of course there are Chinese values that I hold close to my heart — ideals such as selflessness and holding the utmost respect for elders — but the generation gap between my parents and me has made me appreciate the good parts of both Chinese and American culture.

I’m happy to let go of the racist and sexist undertones of my parents’ generation, and in some ways, I’m glad that a few of their values set an example for exactly what I would grow up rejecting.