Sunday morning, 9 a.m.

The suburbs of Fremont are quiet, but Tang Academy’s inconspicuous classroom, a converted garage, is bustling with cars and drop-offs. Still painted a fading white and framed by cypress trees, the garage shows no exterior signs of change.

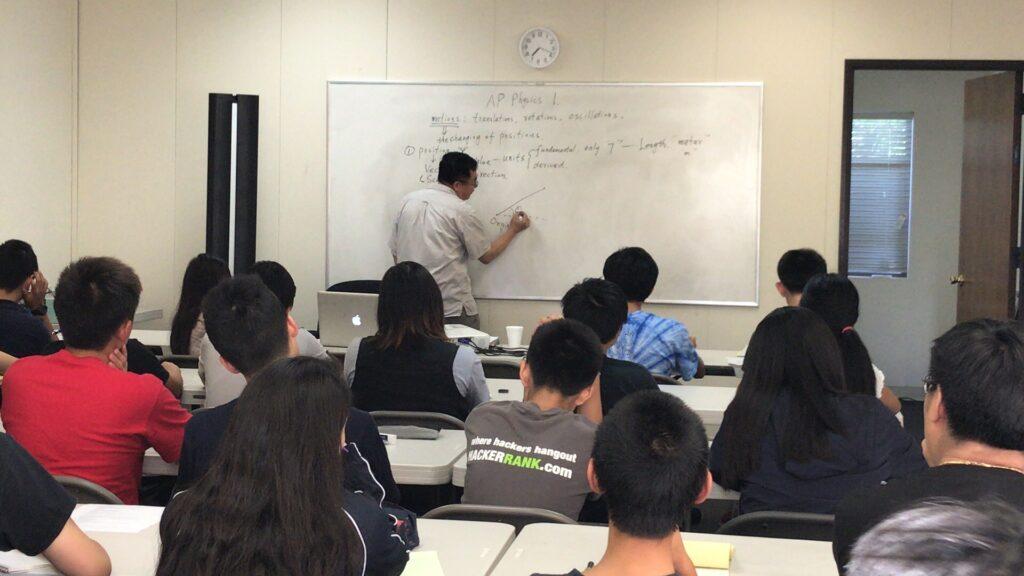

Inside, high school students and precocious eighth graders are taking physics classes taught by an ex-NASA physicist named Huabin Tang, a balding, middle-aged, Chinese man. Always donned in a sweater, he speaks accented English in measured words.

The garage, now a relatively spacious room with a hardwood floor and bright fluorescent lighting, has vestigial panels on the side and no insulation. A projector is mounted above the whiteboards in the front. Tang teaches in front of the teens with a marker in hand.

Forty kids, all between ages 12 and 17, attend each session. Some listen. Some don’t. Some enjoy the class, and some are almost numb for its three-hour duration. Still, they share many traits. Almost every one of them is Chinese American. Almost every one of them passes the AP Physics class at their respective high schools with ease.

Among local Asian American parents, Tang is revered as one of the best physics instructors anywhere. For them, the once-a-week class for $110 a session is a small price to pay for admittedly spectacular results. Most impressively, Tang doesn’t advertise; instead, his reputation has been built on word of mouth.

“We only teach a small group of students based on referrals,” Tang wrote in an email to The Falcon.

Tang Academy is hardly unique. The demand by the Asian American community for academic instructors who teach contest-prep curricula has led to dozens of similar teaching institutions such as Springlight, IDEA MATH and AlphaStar.

Unlike many tutors, these institutions are not designed to supplement a below-average student’s high school education. These instructors teach almost exclusively to above-average Asian American students with the goal of pushing them to their maximum potential, which generally means preparing them to compete in high-level STEM competitions. Among the ones Tang prepares his students for are the F=ma (a mechanics-based physics exam) and the USA Physics Olympiad (USAPhO). These pose a serious challenge to Tang’s students, who find the AP Physics exam almost trivially easy in comparison.

Big fish, small fish

With the high demand for contest-prep education in the Bay Area, the managers of these institutions have specifically tailored their classes to their customers. Sherry Wang, founder of the college-prep company Springlight, located in Cupertino, offers classes with a size of roughly 10 students. In comparison with the bigger players, IDEA MATH and AlphaStar, whose classes contain 25 students on average, Springlight’s classes are smaller and more affordable, if less prestigious. Wang hired her first instructors off Craigslist and friends’ referrals, whereas AlphaStar employs American Regions Mathematics League (ARML) problem writers.

The managers of more prestigious institutions can charge a premium for their services. Tang charges between $35 to $40 an hour for his three-hour physics classes, which contain about 40 students each. Similarly, IDEA MATH charges $695 for a weeklong camp and AlphaStar (owner of the now-defunct AStar) $1,100 for 12 two-hour sessions.

Springlight’s classes deliver a blend of lectures and problem sets. Students meet weekly and have assigned homework. Tang, too, follows this teaching format, but the larger student-to-teacher ratio in his class limits the interactions between them.

Both Springlight and Tang Academy’s classes function like traditional classes, albeit with the intensity turned up several notches. These smaller institutions generally rent office spaces to run their classes, although Tang uses his converted garage.

On the other hand, larger institutions such as IDEA MATH and AlphaStar Academy often function more like bootcamps, offering one- or two-week camps for eight hours a day, six days a week, in rented campuses. They provide many classes concurrently, each designed for students of a specific skill level. Most of all, the classes are taught with a problem-driven paradigm, forgoing traditional lectures.

“The instructors [at AlphaStar] walk you through a couple examples then let you loose,” said sophomore Albert Ye, who came away with mixed opinions about AlphaStar. “We solve problems in two-hour blocks, and afterward the instructor walks us through the solutions.”

Most institutions follow the classroom-like teaching style, with only the biggest companies running bootcamp-like classes. Many STEM competitors in the Bay have taken both. Picking between the programs and finding the one that works best is a process of trial and error, Ye said.

Attendees strive for common goals

Ye is a typical attendee of AlphaStar and IDEA MATH. He has taken classes at both institutions for the past two years, most recently the USA Computing Olympiad (USACO) Gold class at AlphaStar class last winter. He often sports a Toga Junior Math Club hoodie, and he is taking AP Calculus BC as a sophomore.

Ye said his motivation for continuing to take classes at AlphaStar and IDEA MATH is somewhat ambivalent. His decision to continue attending comes down to inertia: He has been practicing competitive math since elementary school, and he has not stopped since.

“If I told my parents today that I would never do math again, they would probably be okay with it,” Ye said. “They wouldn’t disown me.”

At the moment, though, his inertia has halted. He has been working on passing the USACO Gold test for over a year. Ye is one of the students in his AlphaStar USACO Gold class who finds the class’s current level too easy but the next level — at least so far — too difficult, a common situation faced by students taking these classes.

Inertia does not entirely tell the story behind Ye’s decision to take competitive STEM competitions in the first place. Ye himself started competitive math in elementary grade, when peer pressure and his parents had a much bigger say in his extracurricular involvements. Like many STEM competitors at Saratoga High, he has had a path in STEM laid out for him and is continuing to follow it.

Even so, Ye’s opinion of the classes is mostly positive. He said that the most helpful aspect of the classes is the way it gathers people of similar skill levels to discuss and solve problems together, which is missing from similar student-run organizations such as the Saratoga Math Club.

One particular question many students grapple with is whether to take the class instead of studying the material alone.

For sophomore Weilin Sun, that line is drawn right after the beginning of a student’s contest preparation. Sun is working on passing USACO Silver, and he has taken classes at AlphaStar for the past couple years.

“At the mid-level, you should look for a private tutor to help out with your bad topics,” Sun said. Another gripe Sun has with the classes the institutions offer is that the teachers are sometimes unwilling to admit any errors they make.

Despite these drawbacks, the results these grueling classes produce cannot be denied. Ye saw a drastic improvement in his skills the first year he took classes at AlphaStar.

“It’s positively affected my conscious performance. I took the USACO Silver class and proceeded to pass it the same year,” Ye said.

He added, “Contest prep programs are helpful to the degree that you make them. These classes are a supplement if you’re actually trying to get better. If you’re being forced by your parents to do it, there is no way you’ll improve.”

Practice, grueling practice

For some students, the question of taking the classes is a secondary motivation to learning STEM itself. Junior Christine Zhang, for instance, has doggedly continued competitive physics into her junior year, an age where many of her peers have already quit from mounting pressure in schoolwork and a waning interest in STEM.

Following in the footsteps of her older brother, Michael, a 2019 grad who achieved at the highest levels of competitive math and physics and is now at MIT, she was initially pushed into STEM by her parents. She was forced to attend AlphaStar for three years in middle school and was pushed to attend Tang’s physics classes for two years in high school. Zhang said she is thankful that her parents pushed her in this direction, though her initial reaction to AlphaStar in middle school was a feeling of hatred and inferiority.

“I did not enjoy being there,” Zhang said. “I thought, ‘Everyone is so much smarter than me. Why am I even here?’ That gave me a permanent hatred of competition math and AlphaStar.”

Looking back now, Zhang faults herself for her negative experience at AlphaStar. It was her own apathy for competitive math, not the camp itself, that made AlphaStar unenjoyable, she said. It took Zhang years to reach her current relationship with these STEM competitions and their classes: an amalgamation of self-motivation, duty to her friends in those classes and the same inertia that Ye felt.

“I don’t know how to answer what keeps me going,” Zhang said. “It’d be nice to get an honorable mention on the USAPhO, I suppose.”

Zhang views the classes as wholly unnecessary for success, a common sentiment among the competitors. To her, the classes are simply a rehash of openly available test-prep materials, often presented too quickly and confusingly. She succeeded in Tang’s classes only when she previewed the material and arduously pored over her physics textbook at home. Nevertheless, she continues to take physics classes and is now at Springlight rather than Tang Academy.

Zhang’s biggest takeaway from the classes is the worldview she holds, not the material itself.

“There are always going to be people better than you,” Zhang said. “The classes were just me learning that there are people better than me and I should just suck it up and keep studying on my own because that’s what’s important.”

Her persistence has paid off. Zhang said she made two good friends in Tang’s classes and discovered a liking for physics. This year, she qualified for both the American Invitational Mathematics Examination (AIME, the next test up from the AMC 12) and the USAPhO. Her background in physics and mathematical problem solving is helping her in AP Calculus BC, AP Physics and AP Chemistry at school.

Zhang summed up her experience succinctly.

“I suffered a lot, but I’d do it again,” she said.