One day, while learning about World War II in World History, my teacher began talking about how Japan’s annexation of Korea resulted from imperialist motives. This perspective, I realized, was awfully different from the one I’ve known my entire life from my parents, who told me Japan, an island country isolated from the continent, took control over Korea in order use Korea’s supply and to give its troops a military base so they could further reach out to Qing Dynasty (China) and Russia during WWII. I began to question which one was truly reliable: what I learned in school or what I learned at home?

George Orwell, renowned for his novels “Animal Farm” and “1984,” once wrote that the most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.

I had always assumed that history taught an unbiased representation of the world. But every generation has heard of the cliche: “history is written by the victors.” There is a significant difference between what students learn from a history textbook at school and what they might learn from their parents at home. As for Japan’s annexation of Korea, the Japanese and Koreans have vastly different interpretations of what actually happened.

This means our education system faces a challenge in providing an unbiased account of history. Right now, many history classes and materials enforce students to accept biased versions of historical events as the only truth, failing to acknowledge different perspectives.

It’s evident that history is interpreted in many different perspectives, and by comparing the historical interpretations on textbooks, it’s also clear that history textbooks are unable to serve as an impartial educational tools that simply teach students facts and skills because textbook authors assign positive or negative interpretations to particular events. But has it gotten any better?

As a democratic society, one of our educational goals is for schools to foster socially conscientious students who are able to view situations impartially and utilize their own critical thinking skills to create their own opinions.

However, most history textbooks tend to describe historical events in a manner that promotes a narrow and unarticulated worldview. The language prominent in history textbooks tells students what to think, rather than allowing them to assess the facts and formulate their own take on the situation.

Even in making judgments about what facts or events are included in a textbook, authors convey implicit views of history. What students take away from history books is often not the facts of events themselves but an overall tone or impression toward them. By being selective of their content, textbooks that are factually correct may still be communicating moral judgements. Although this form of bias is more subtle, it is still powerful, and greatly impacts what students take away from history classes.

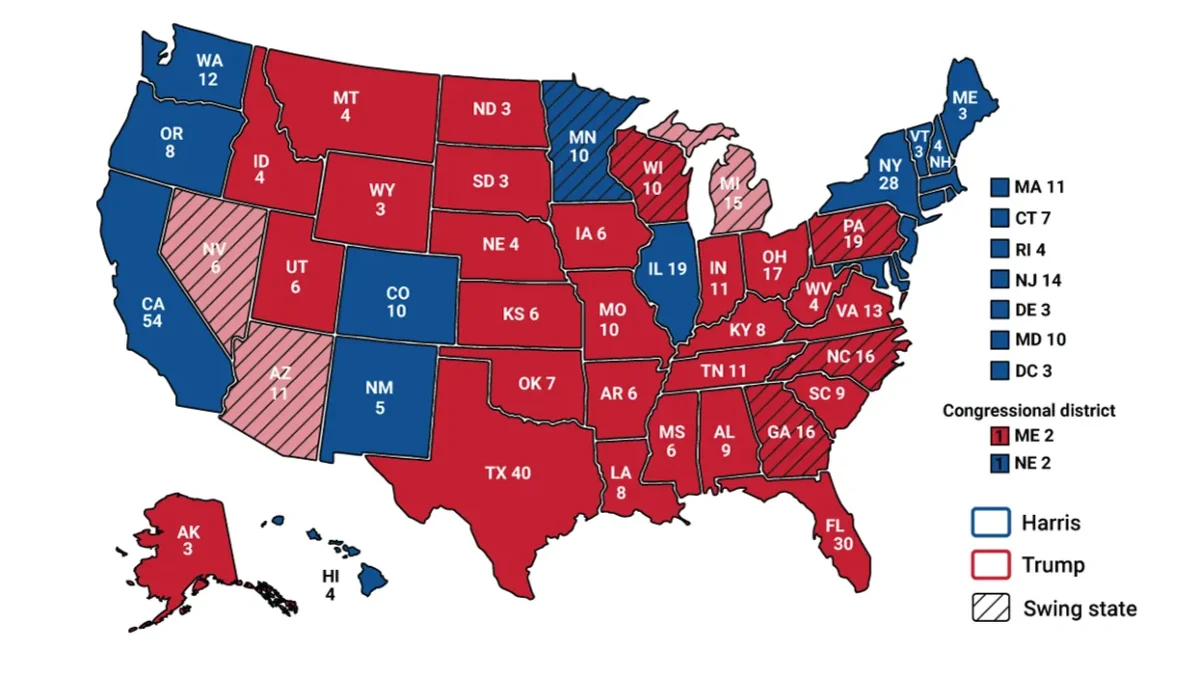

History textbooks are subject to a variety of biases — factors such as where they’re published, who is publishing them and in what context they’re being used. As a result, the “truth” that they provide can often be skewed towards a particular view.

In fact, for many years, American history was told largely from an exclusively white point of view. Only recently have we been considering other voices in history: Native Americans, African Americans and Asian Americans to name a few. Moreover, many historical events are interpreted in an exaggerated way that proclaims America’s superiority toward other countries.

In recent years, there has been progress on this front. For example, APUSH teacher Faith Daly incorporates more material in her curriculum from differing perspectives, such as the Native American documentary “Our Spirits Don’t Speak English,” in order to provide students more informed view of historical events. Also, according to the recent study issued by National Association of Scholars (NAS), the College Board is adjusting its courses for exams including APUSH and AP European History.

Nevertheless, there is still much to do to; educators worldwide should apply these practices to all major historical events, ensuring students an accurate, comprehensive picture of history.

Instead of providing readers with a single, narrow recollection, history textbooks should instead aim to give readers a maximum number of perspectives on any given event. Students also have a responsibility to be aware of possible biases in the material they study and consider different voices in historical events. Readers can then come to their own conclusions, based on not only an unbiased representation of history, but in conjunction with information provided by other resources.