When you visit a fencing club, perhaps the first thing you notice is the noise: the sounds of metal on metal as blades cross and the thud of feet hitting the floor as kids advance and retreat up and down their strip, trying to score on their opponent. They push themselves to sit lower, move their feet faster and try new ways to hit their target.

The sport of fencing consists of three styles: foil, epee and sabre. Each style has a different weapon and target to score on.

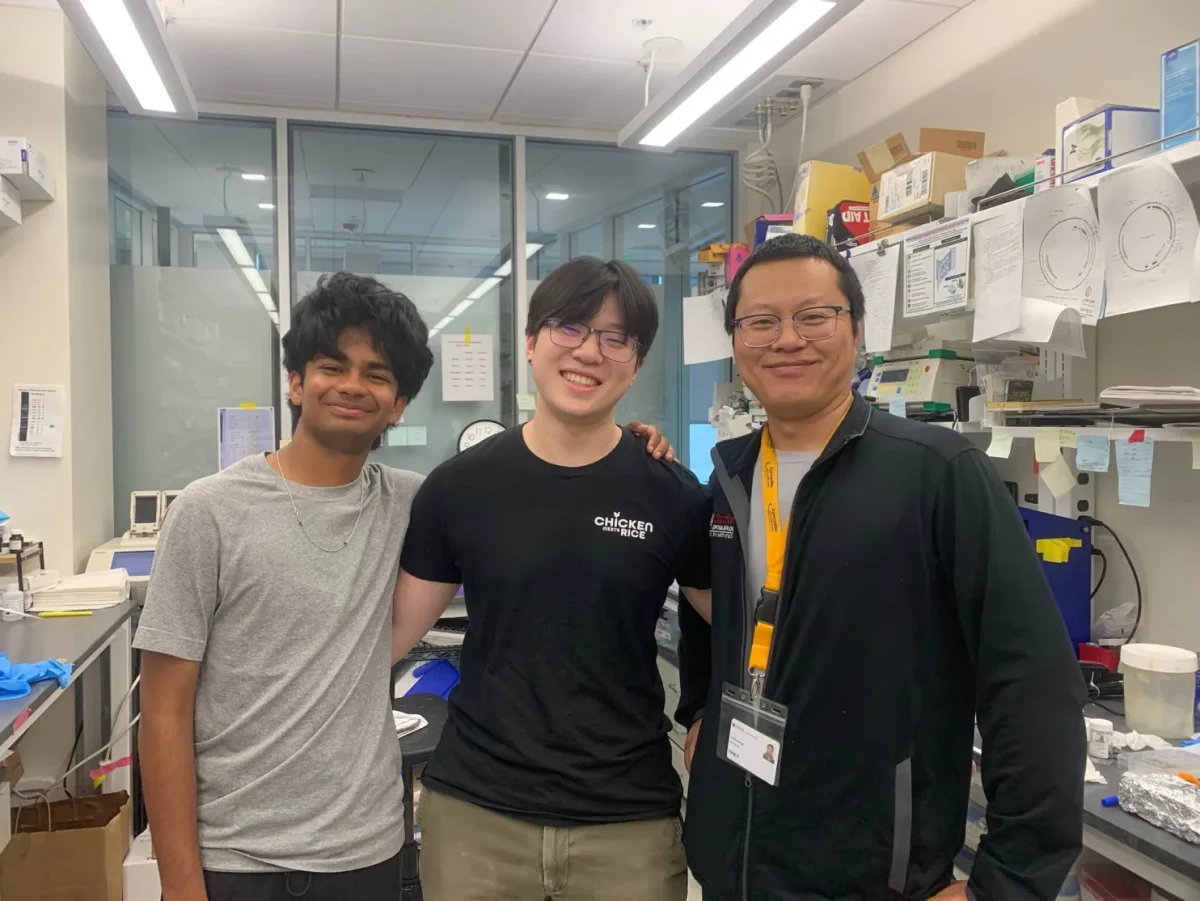

The school has about a half dozen competitive fencers, including me. Fencers in each style dedicate hours of their time and energy into improving their skill and technique. Our school nights are packed with practices, and our weekends consumed with competitions in far-flung places.

Senior Ria Jobalia, who fences epee at a national level, said her practices take up a large chunk of time each day, and the hours add up as the week progresses. Jobalia got into fencing as a child after a grass allergy prompted her to find an indoor sport. She thought the swords used were cool and decided to try it.

Jobalia said she now practices four days weekly at Academy of Fencing Masters in Sunnyvale. Three of her practices are two hours long while the third is three hours long. In total, Jobalia spends approximately 15 hours a week fencing.

Training consists of a variety of activities that focus on improving aspects of a fencer’s performance. Practices start with a warm-up of running and stretching as well as conditioning. Most of her time is spent improving footwork, tactics and techniques in drills and practice bouts. The drills done in practice target certain areas — mental or physical — that fencers struggle with

“The hardest part about fencing as a sport for me has always been the mental side of it,” Jobalia said. “Changing strategies when my opponent figures out what I’m doing, staying focused throughout a whole day of competition, not letting one bad bout get to me.”

Additionally, one of the biggest hardships Jobalia and other fencers face is time management; the long practices can make it difficult for many students to keep up with their academics. Sophomore foil fencer Jason Chin said he learned that managing his time well was essential to completing the work he needed to get done.

“I’ve learned that I can’t really goof off as much as I wanted to,” Chin said. “There’s no time for me to do other stuff.”

To ensure that they get everything done, fencers create strict schedules. For Jobalia, it is imperative for her to start homework as soon as she gets home from school. Chin, who practices at the Massialas Foundation in San Francisco four days a week, must complete his schoolwork while waiting for his practice to start.

“My brother starts before me, in the earlier class,” Chin said. “So when he has his class, I’m doing my homework while I’m waiting for my class to start. If I’m not done by the time my class starts I just finish the rest when I get home.”

Along with attending practices, many fencers compete in local or out-of-state tournaments. Jobalia and Chin both compete about twice a month, often traveling out of state.

Fencing competitions can sometimes last up to six or seven hours. According to Chin, there are many of people around, as well as noise and other distractions, which can make it hard to focus school work and a little stressful. Even so, Chin finds that the fun of competing outweighs the stress of always being so pressed for time.

“The best thing about fencing to me is the amount of friends you make,” Chin said. “I’ve traveled to many different countries for tournaments and I’ve made a lot of connections.”

In addition to creating relationships, fencers learn skills that can be applied to other aspects of their lives.

“The most important skill I’ve developed at fencing is probably my ability to stay calm no matter what,” Jobalia said. “When I’m losing a bout, I know I have to stay calm because if I get nervous and jittery, I’ll lose my focus and lose. This helps me a lot on a more regular basis because before a big test or anything major, I can always keep my calm and go through anything pretty relaxed.”

However, the steep time commitment required for fencing remains a consistent obstacle. As competitions further impede on time spent on homework and class time, fencers use the plane rides to and from tournaments to complete assignments to make up for lost time.

While some students are ultimately able to balance fencing and schoolwork, it can be more difficult for others. Junior Derek Shay, who once fenced four days a week and competed every two weeks, had to stop due to the toll it was taking on his academics.

“It’s honestly a big strain on homework and school so that’s why I stopped a year ago,” Shay said. “It often interferes with my work and my grades were slowly dropping.”

Those who continue to fence inevitably tend to find it difficult to balance with studying. Jobalia said that during AP season of her junior year it became difficult, leading her to miss several weeks of practice, since there was “too much going on at once.”

Despite the struggles they face, fencers still find the sport worth the time and dedication.

“I like how when I fence my senses and adrenaline takes over and all that matters is beating the person in front of me,” Chin said.