Seven years ago, my family moved from Saratoga to an upper-middle class neighborhood in Houston, where I resumed second grade. Perhaps not surprisingly, my predominantly white classmates expressed confusion over my ethnicity.

My skin tone certainly didn’t match most of theirs, but my name was ambiguously Caucasian-sounding enough to intrigue them. I’m not sure how they rationalized my appearance, but I knew they were having their epiphanies that I was biracial when they would say blatantly, “Gee, your mom is Chinese and your dad is white.”

I also don’t blame them — many were unacquainted with Asian culture. That didn’t make them racists — we were about 8 years old. Even if I had never been questioned about my race before, I never felt uncomfortable or thought anything of their questions.

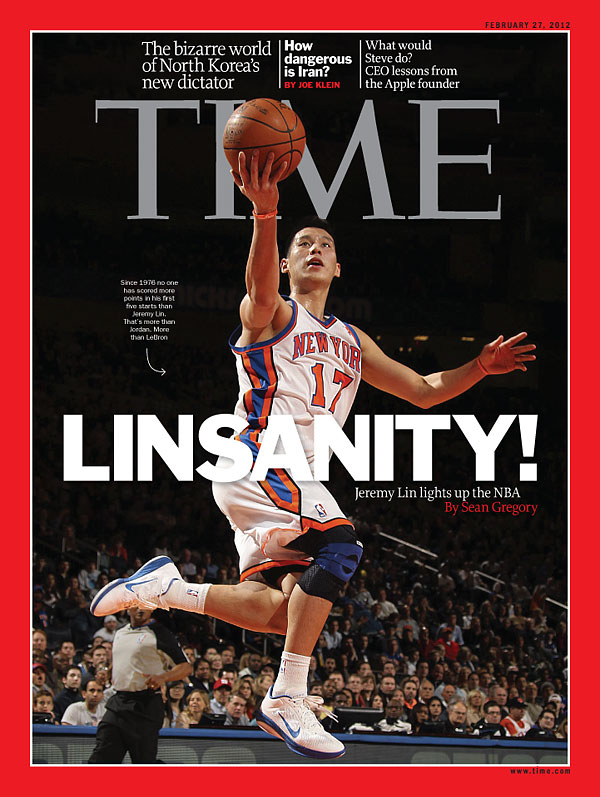

Over the years, I’ve noticed that people tend to perceive the “other” first — the part of my background that isn’t similar to theirs. When I visit my mom’s side of the family in Hong Kong, the majority-Chinese population points out my white appearance, while my Caucasian peers in Houston saw my dark hair and eyes.

After moving back to Saratoga in 2015, these traits blend in, but I get my share of curious ethnicity conversations with friends and teachers.

People ask variations of, “You’re not full?” The “Asian” is implied.

These are innocent questions, and I’ll usually laugh them off — it can be an interesting conversation starter.

But those questions coming from a closer friend can be, frankly, weird. I would expect them to put two and two together — I mean, my last name is Hartley.

Anyway, in 2018, how much does my racial background matter? My Asian and white combo will really only be considered by the U.S. Census. And maybe College Board.

When applying to colleges, I’ve been told to mark “white” rather than “Asian” in order to curb any possible disadvantages due to affirmative action. I’ve even heard my friends fretting over hiding their Asian background in their applications, joking about changing their names to sound “white” like mine.

When my Hong Kong-born mother told her friends and family that she wanted to marry my dad, a third-generation British white guy from Massachusetts, they weren’t shocked. Her sisters also had white spouses, and they had largely assimilated into American culture.

Sixteen years later, we’re back in Saratoga, and grocery store cashiers still ask my parents “Are you two together?” and glance back and forth between my parents and me, trying to fathom this “Wasian” — half-white and half-Asian — girl in front of them as they pack our goods. Although a mixed-race couple may face a lot of judgment in the Midwest, my parents haven’t experienced stigma for being a couple in the Bay Area, even if people don’t always immediately recognize them as being a couple.

My dad said that the only times he becomes aware of race occur when the confused clerk at Trader Joe’s asks if they’re together. Although the sight of a mixed-race couple will be a surprise to some individuals, the culture of diversity in the Bay Area contributes to the normalization of mixed-race couples; many of my family friends are also mixed-race couples who met in the workplace.

At home, my mom cooks food from a plethora of cultural cuisines, and although my dad may crave a tuna sandwich over fried rice sometimes, our home cooked diet doesn’t correspond with Chinese any more than it does British.

Of course, my mom always teases that the occasional double-takes I receive when I’m with both of my parents are due to my stunning half-blooded good looks — especially when we visit Hong Kong, where people tend to immediately recognize me as half and half.

Some people who are aware of my Wasian-ness will occasionally subject me to obscure Wasian stereotypes: “Some Wasians are super good at math,’ or ‘Wasian people are attractive!’” I’ve heard them all.

Racial stereotyping is obviously not unique to any one race, but one element that might be specific to people of mixed ethnicities is dissecting their cultural backgrounds. I’ve had people analyze my face for white versus Asian traits and even decide that my outfit or water bottle made me more white than Asian. Most of the time, they address the most obscure things, as if having a golden retriever makes me any more white than the next dog owner.

I have been fortunate not to have been subject to any truly negative experiences due to my mixed ethnic background. While I may be genuinely open to friends’ curiosity about my mixed race and laugh about the nature of Wasians, I think individuals generally want to be perceived as themselves, first, without any racial labels.