After months of gathering data from national and state polls, political analysts and statisticians predicted a clear Democratic victory leading into Election Day. Many projections, including ESPN’s FiveThirtyEight, Huffington Post and The New York Times set Clinton’s chances of winning the presidency to be over 80 percent.

Yet, on the evening of Nov. 8, The New York Times’ projection of Clinton’s chances plummeted horrifyingly below 5 percent while Trump’s soared to over 95 percent — everything the national and state polls had predicted was overturned in less than three hours.

Undeniably, polls do not provide a full picture of voters’ stances. Generally, national and state polls are conducted with a sample of about 2000 subjects, who are interviewed live over the phone for 15 to 20 minutes.

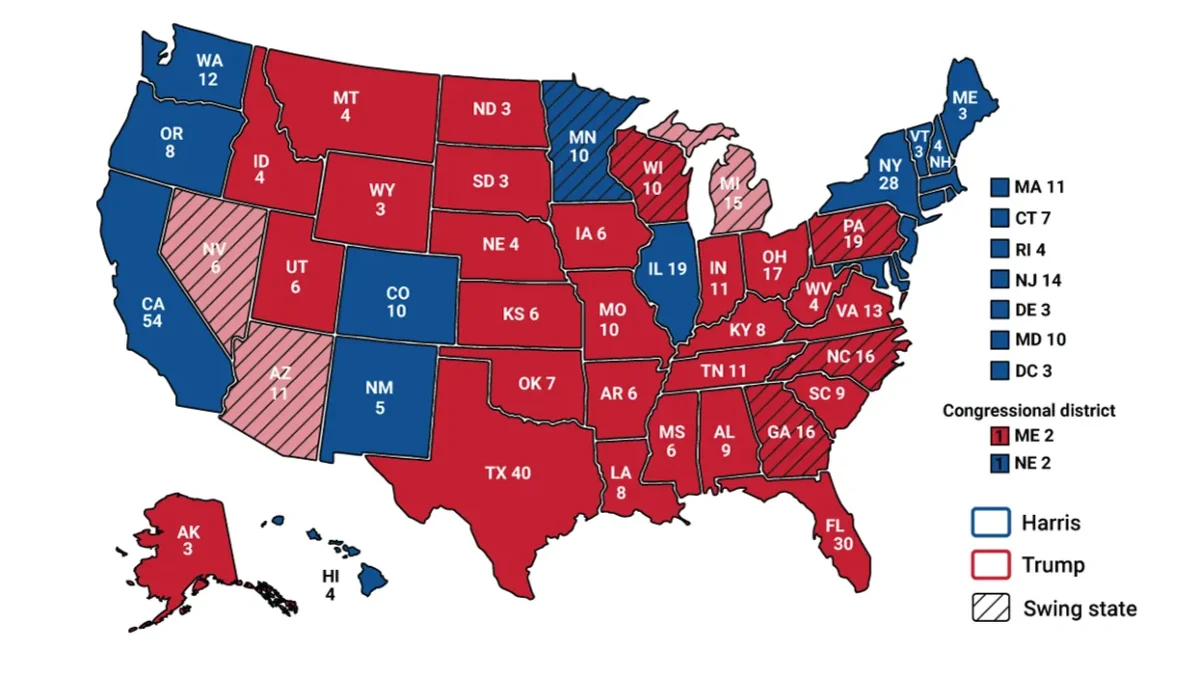

National polls that assess candidate popularity cannot accurately predict a victor, as proven in the 2000 presidential election, in which Democratic candidate Al Gore won the popular vote against George W. Bush but failed to gain the required 270 Electoral College votes to win the overall election.

Similarly, in 2012, Republican candidate Mitt Romney was ahead of Barack Obama in Gallup and Rasmussen polls, but Romney ultimately won neither the popular nor majority vote in the Electoral College system. With the recent election again questioning the validity of national polling, it’s clear that people should not be looking towards national polls to place their bets on a winner.

More pertinent to projections are state and exit polls, which, unlike national polls, can give some insight into the number of Electoral College votes a candidate is likely to secure.

Nevertheless, they have been proven to be unreliable, and part of the inaccuracy owes to the method in which the pollsters conduct their polls.

Live interviewing is intimidating — and with the sharp division of the Democrats’ and Republicans’ political and moral philosophies and the insults being hurled from one party to the other, subjects can easily be discouraged from voicing their true opinions to a stranger on the phone.

If live interviewing is not preferable, could pollsters rely on online polling instead? Simply put, online polling may not be any better than live telephone interviewing.

For online polls, only those who have access to the Internet will be able to respond, creating a situation in which the younger, more technologically dependent generation is overrepresented. The issue lies in how age and voter frequency vary inversely; the older people are, the more likely they are to vote. While the younger millennials may voice their opinions and click their preferred candidate on a website, they may not actually be willing or able to cast a ballot on Election Day.

The final downfall of the poll is the manner in which pollsters account for an inconsistent sample by weighing their subjects’ responses.

For example, in a case in Los Angeles, one black man’s vote was used as a representative of all African American votes. Such a generalization creates a margin of error that leads to a lack of precision.

Additionally, how the pollsters choose to weigh their results is completely a personal choice. A common practice is to track the trends of other polls and weigh responses in a way that agrees with the general average. In doing so, changes in public opinion may not be accurately represented.

The shortcomings of the polling system have gone under the radar in the years up until this recent election, which seemed to have magnified its flaws. Looking back at the many times state polls and the projections have hit the mark, polling still holds some merit in representing a portion of voters’ stances.

However, going into the future, it is important to remember that polls are just snapshots of certain people’s positions at a particular point in time. Similar to the way photographers can Photoshop images to their liking, polls can be manipulated and processed by pollsters to agree with what they believe is the norm.

Because of the way data is gathered and processed, voter stances may change well before they are reflected in the polls. But by then, it may be too late to be surprised by the results.