“That test just raped me”; “that was so gay”; “n****.”

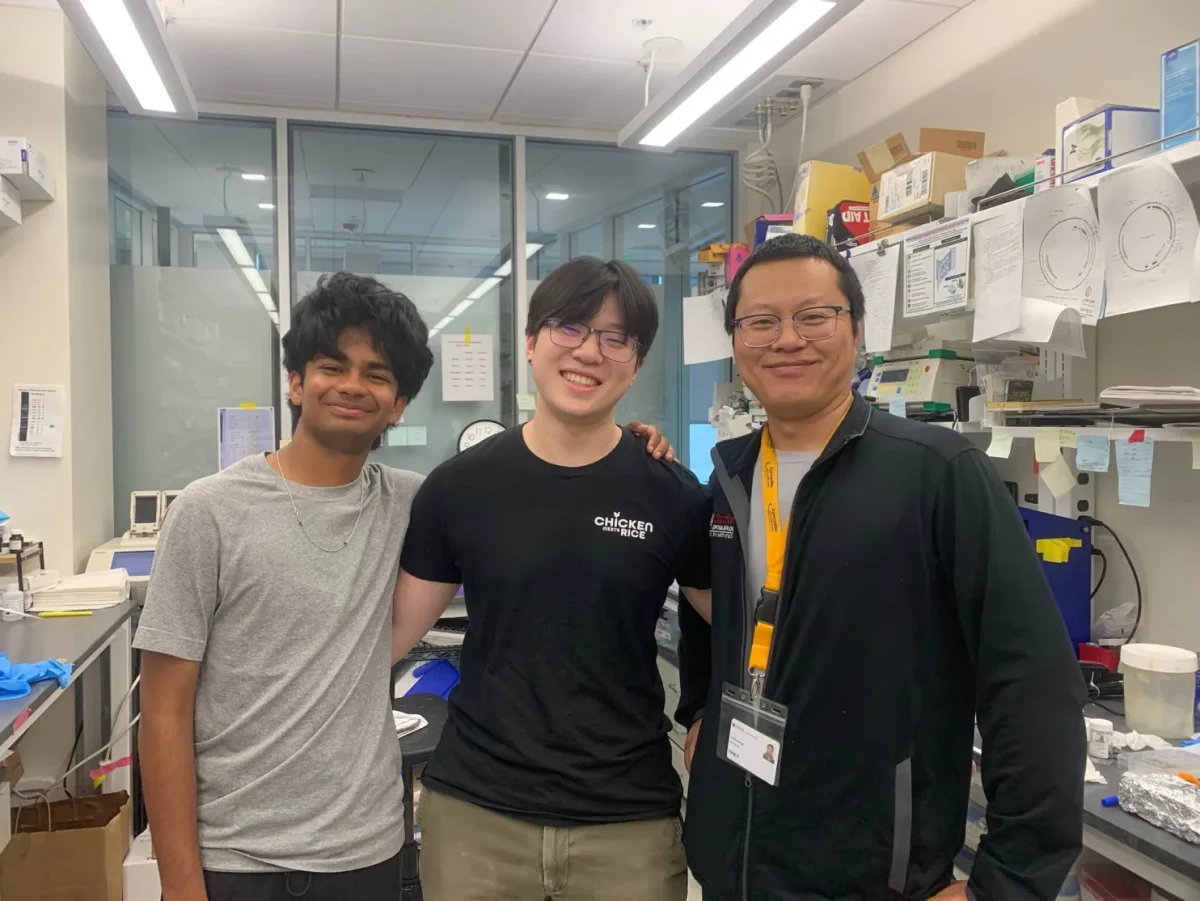

Junior Nathan Kang has heard all of these phrases used in person and on Facebook messenger. Kang himself admits to using some of these terms before, mostly unaware of their historical and offensive connotations.

“What people don’t realize is that these words, when used as insults, are basically calling someone less than human,” Kang said. “That’s not cool in general, but I think many students don’t think about the meaning behind these words when they say them.”

Kang said he’s only recently realized the importance of knowing the meaning behind different words. Specifically, he recalls watching the movie “Twelve Years a Slave” in English teacher Meg Battey’s English 11 class. After seeing enslaved African Americans called the n-word by abusive white slave masters, Kang said he realized that this word was not just an insult, but a way to demean slaves as less than human.

Similarly, English teacher Natasha Ritchie also decided to show this film to both her honors and MAP students in order teach students the importance of language. Ritchie said although she mostly focuses on writing, reading and grammar, these elements of English all depend on an understanding of words and how words have power.

When students read books such as “Beloved” by Toni Morrison — a novel based on the post-Civil War life of a female slave — it allows students to realize that Morrison is “crafting an idea for you in language,” Ritchie said.

“I think it’s just a good idea to ground yourself once in a while,” Ritchie said. “And ask ourselves, ‘Do we really think about what we say?’ and ‘How much conscious filtering [do] we do?’”

In addition to “Beloved,” Ritchie’s students also read “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, a novel that outlines the journey of a runaway slave and a white boy. With both of these novels, Ritchie teaches that there are so many ways to dehumanize people, and one of the most prominent ways is through language.

“I don’t think we think about language as having dehumanizing power very much,” Ritchie said. “We think about physical abuse, brutality or violence, but the mental abuse is always language based.”

Junior Vivian Luo recalls her presentation on “Huckleberry Finn” in Ritchie’s English 11 Honors class, during which she mentioned the censored a version of the novel that replaces the n-word with the word “slave.” Despite the censored version’s intention of protecting young readers from strong language, Luo believes this editorial choice lessens the novel’s message about the impact of slavery.

“I think reading the uncensored version in class makes us realize the effect that words, like the n-word, have on people,” Luo said. “In many ways, this word captures the discrimination African Americans faced in America at the time.”

Ritchie says she is not a fan of censoring language because she feels that history cannot be censored.

That said, Ritchie believes that these novels with such powerful or controversial language should not be taught without discussion of words. Then, Ritchie said, the words just “sit out there. And that’s not good either.”

“I think it’s kind of absurd to say, ‘My delicate sensibilities cannot read this word in this book,’” Ritchie said. “But what about the 60 million people that Morrison dedicates her book to who actually heard the word directed at them in a derogatory way?”