In most families, kids learn to be responsible for themselves, and only themselves. But in my family, it’s different. Soon after my younger brother was born, it was obvious life with him would be different.

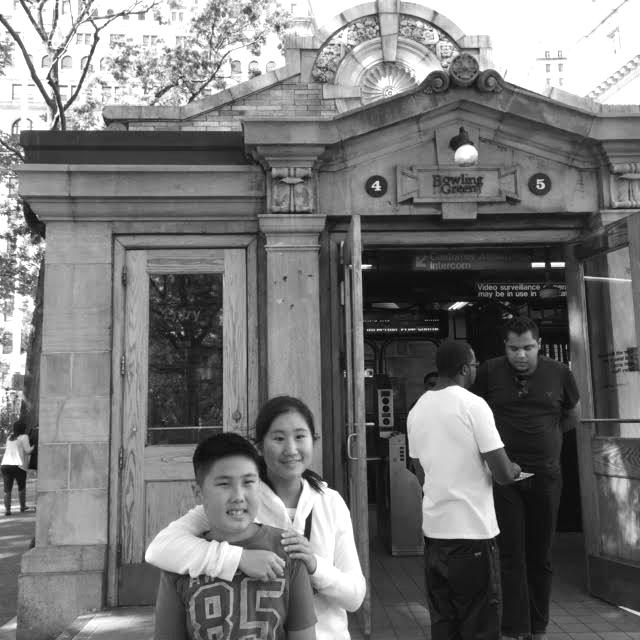

Brent is the brightest, most cheerful, affectionate 13-year-old I know. I remember him sprinting after a mud-stained soccer ball during practice, sunlight shattering against his dark hair like a broken halo. And the pair of floppy red and blue oven mitts, too big for his hands, as he pulls out a fresh tray of banana muffins that he baked himself. Or that one time during family karaoke night when he whispered the lyrics of “Let It Go” from “Frozen” into the microphone.

When my mother first heard his diagnosis from his developmental pediatrician, she felt like the world stopped spinning. She feared her fear, sadness and guilt would spill over: Did she do something wrong? How will we handle this as a family?

For me, being only three years older, that understanding came later. I wondered why he refused to eat at preschool or sleep during naptime. I’d ask my parents why my brother still cannot speak, why he loved organizing his cards and bouncy balls into certain piles. They said he learns differently from me. It would be a while before they tell me the whole truth.

When they do, my 7-year-old, 8-year-old, 9-year-old hands crumple into fists as I see my brother’s classmates push him off his bike. The burning steel of his dusty red tricycle slams into the tanbark. Embarrassed, resentful and furious, I wanted to scream at them. I wanted to hit them for hitting my brother. But my parents pulled me back.

“They don’t understand,” my mother says gently. “I will talk to them later.”

When my parents finally told me the source of his differences, my life found a new center, winding around my brother’s like a protective hand. My father’s reminders to protect him, to look after him when I grow up, enclosed upon me. Somehow my successes and aspirations started to not only reflect myself, but also my brother’s future. I feared failure because it would mean letting him down. I wondered if I’d be capable of looking after him when I already had trouble taking care of myself.

Meanwhile, slowly and determinedly he is getting better at speaking. Unlike me, he loves doing his homework for his seventh-grade classes. His smile glows in the dusty light of the desk lamp as his tutor tells him of the technological advances of ancient Mesopotamians and of the 9-11 Memorial in New York. His scribbles are becoming more and more legible. He began replying to our questions:

“How are you?”

“What school do you go to?”

“What did you do today?”

Recently, he brought home an abstract painting he made from oil and marbles — it reminds me of a volcanic explosion. The angry pink, white and orange splatter hangs in a silver frame by the kitchen table. And one morning, as I entered the living room, he paused the song playing on his iPad, leaned over to me from the couch and spoke to me on his own for the first time.

“You are awesome,” he said.

At the end of the day, I love my brother. I realized how selfish and conflicted I felt. He is not a burden. He is not just a dependent person, and has talents and abilities of his own. He is a person, and a lesson. My bond with him is not just reliance. It is joy. It is innocence.

It is love.