Editor’s Note: Corrections were made to this article on Dec. 8 and are reflected in this online version. On Nov. 14, 2014, The Falcon published an article entitled “Tutoring in the shadows.” Although we believe that the article was largely both accurate and fair, the article inaccurately described certain situations or statements. In particular, it inaccurately stated that Samuel Breck was “shocked” by finding that Spotlight Education had materials from Saratoga High School teachers, when in fact Breck only stated that he didn’t expect Spotlight to have such materials. The article also inaccurately indicated that Breck had noted “startling similarities” between multiple quizzes he was provided with by Spotlight and quizzes subsequently given in a class he was taking. Breck indicated that he was surprised that one quiz he was provided by Spotlight was the same as a quiz subsequently given in his class, and indicated that other quizzes provided by Spotlight tested the same concepts addressed in quizzes given by his teacher. However, he did not say that the similarities in other quizzes were startling. Addressing why Breck did not speak to others about his experience with Spotlight, the article omitted part of his explanation. The complete explanation of Breck’s reasons was as follows: “I don’t have anything against Spotlight and I don’t exactly want to get involved in whatever issues they have, first of all because it’s my Mom’s college friend and so I didn’t want to get into the mess of that. I think I didn’t talk about it because of that.” The article also should have noted that both Breck and Meghna Chakraborty indicated that they stopped attending Spotlight after seeing questions appearing on practice quizzes provided by Spotlight in actual quizzes given by their teacher. Finally, in a communication received after the article was published, Spotlight stated that past quizzes constituted less than two percent of its curriculum, and that Spotlight stopped providing past quizzes to students as of Nov. 1, 2013.

Senior Samuel Breck, then a sophomore, didn’t think he was doing anything wrong. During his tutoring session, he was given, as practice, an old quiz for a class he was taking at school.

The next day, when Breck took the actual quiz in class, he noticed something familiar about the questions and the formatting of the page in front of him. It was the exact same quiz — not even the order of the questions had changed.

“I just blasted through all of it; I was really surprised,” Breck said. “I’d shown a couple of other people telling them that this was just one of my study tools, and they were all surprised as well.”

The quiz he received was from a local tutoring service called Spotlight Education, popular in the community for tutoring in classes like Chemistry Honors and Trig/Precalc Honors. According to multiple students who used the service, Spotlight provided old quizzes that proved to be identical to the current quizzes students took in class.

Senior Meghna Chakraborty, who also used the service, said that Spotlight asked its students to save their old quizzes. When Spotlight was told that these quizzes were identical to the ones used to test students, Chakraborty said that her tutor shrugged it off.

The Falcon asked several other companies whether they employ similar practices, including AJ Tutoring, Harvard Square and Spotlight. While it's likely that Spotlight is not the only organization to distribute old quizzes, The Falcon was unable to find students who said they saw the practice occurring at other companies.

Breck’s story is indicative of a larger trend: the use of old quizzes that teachers have passed back as study material. The practice of passing on old quizzes to younger generations, perpetuated by tutoring services, has hurt efforts to encourage formative learning, some educators say.

“We give back quizzes so that students can study from them and learn from their mistakes,” said Debra Troxell, math department head. “If a student knows that we are going to ask ‘this this this and this’ and have the last four years of Ms. Troxell’s quizzes, that just defeats the whole purpose of learning, period.”

In Breck’s case, he did not tell his teacher or inform Spotlight about the similarities between the quizzes he received for practice and the quizzes he took in class, worried he would aggravate the situation.

“Teachers definitely deserve to know that information, but it’s just really hard for the student to come forward because they have a lot of peer pressure from your friends,” Breck said. “I don’t have anything against Spotlight and I don’t really want to get involved in issues they have, first of all because it’s my Mom’s college friend and so I didn’t want to get into the mess of that.”

Tutoring Tales

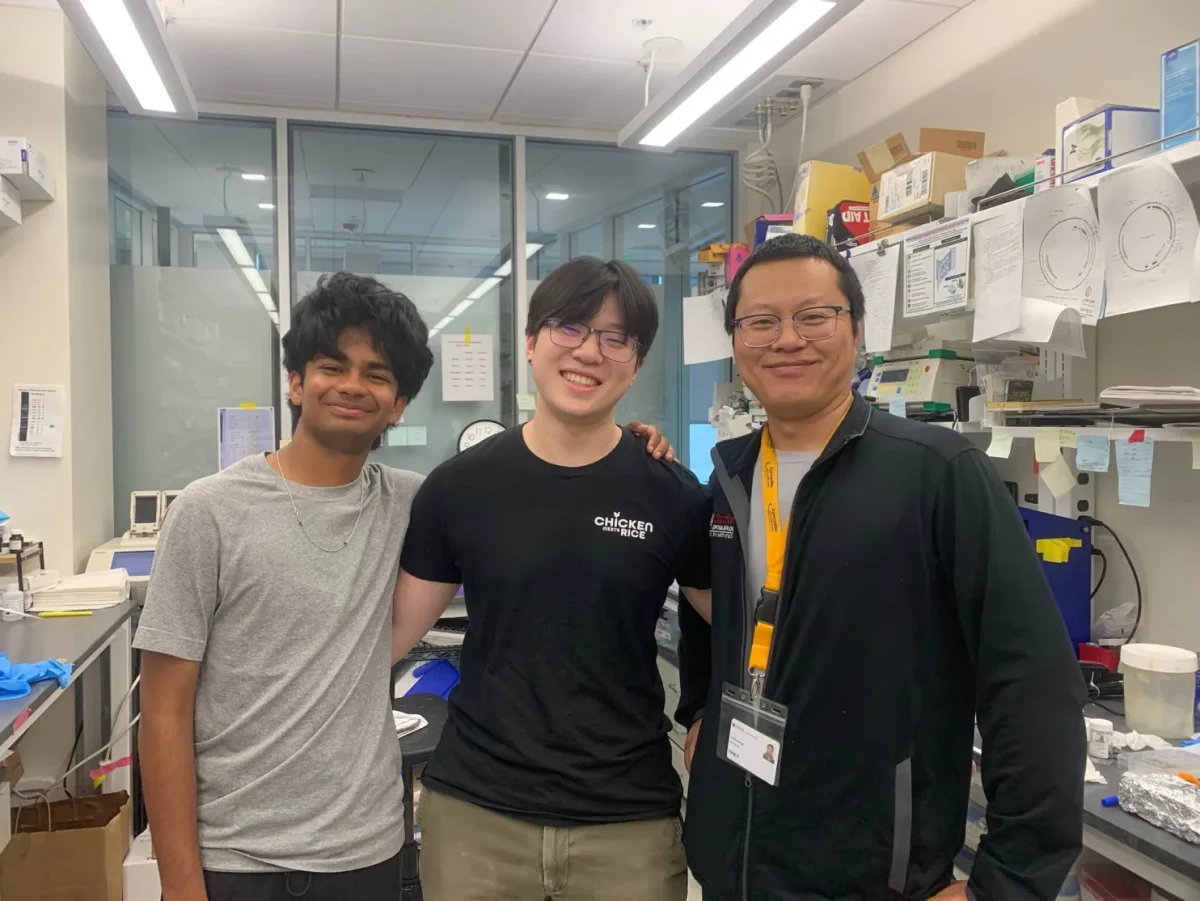

When Breck first walked into Spotlight’s office on South De Anza Blvd. in the fall of his sophomore year, he did not expect to find files of materials from different Saratoga High teachers.

“They have a database, they have a lot of stuff from past classes,” Breck said. “Chung Chiang [Spotlight’s mathematics tutor] has it on his computer, they have it for physics and all the maths. Chung obviously knew a lot about [a particular teacher] because his students would come back and tell him stories about her and give him quizzes.”

Breck said that while surprising, the fact that Spotlight catered its tutoring sessions to specific teachers is appealing because it allows for more specific and directed assistance. During a typical tutoring session, Chiang assigned Breck and other students practice problems from the textbook as well as past quizzes from their teacher. The sessions are $45 to $48 for an hour and a half and take place after school.

“I don’t think he knew [the teacher] would recycle them,” Breck said. “But he told us that these were past quizzes, and most likely they would be similar so [we] might as well just practice them.”

When Breck received the practice quiz that turned out to be identical to the quiz he took in class, he “didn’t give it a second thought.”

“To me a past quiz is just study material,” Breck said. “When I got that past quiz that was exactly the same as the one [our teacher] gave to our class, it’s not like I knew that it was an actual quiz.”

Breck said that he stopped attending Spotlight after he saw questions appearing on practice quizzes provided by Spotlight in actual quizzes given by his teacher.

Breck was not the only one to have seen quiz problems before the actual quiz. Senior Meghna Chakraborty, then a sophomore, said that Chung had given her past quizzes from Troxell’s trig/precalc honors class.

She too discovered that some of the practice quizzes were identical to the real quizzes. Shocked, she and her classmates mentioned the similarities to Chung, who, according to Chakraborty, did not think it was a big deal.

“I knew it was bad, but a bunch of the kids were excited because [they] wanted to do well in the class,” Chakraborty said. “But I was shocked that Chung thought he was doing the right thing, even after the students told him.”

In fact, Chakraborty said that Chung admitted to asking his previous students to save their quizzes, and asked her class to do the same. When The Falcon emailed Spotlight about the issue, Chung had no comment. After she found out about Spotlight's practice of giving old quizzes as practice, Chakraborty left Spotlight because she didn't think it was ethically right or helpful in the long-run to memorize quiz answers.

While most sources agree that students who have had access to quiz problems have an advantage over those who have not, whether that advantage is considered cheating and who is at fault are debateable.

Looking back, Chakraborty said using past quiz material to study is unethical because it creates an unfair advantage. In terms of who is to blame, Chakraborty believes it is neither the student nor the teacher’s fault.

“Although she should know that students here are very competitive, I don’t think Troxell is to blame because she is just assuming people are moral,” Chakraborty said. “I don’t think the students are to blame because they are just handed the quizzes from a company their parents are paying for.

“I do think the tutoring companies are most to blame because they are giving an unfair advantage to the students. So basically you’re paying them for the quizzes,” she said.

On the other hand, alumna Sachi Verma, who went to Spotlight during her junior year, said teachers are mostly at fault for allowing students to keep old quizzes without changing the questions for following years.

“If the teacher gives a student a quiz back to keep, it should be free access for anyone regardless if the tutor had it before,” Verma said. “But if the student got it illegally, without the teacher’s permission, and the tutor wants to take these quizzes, then that is not OK.”

Breck pointed out that tutoring centers are not the only ones to perpetuate the culture of using quizzes as study material. Older siblings or friends may pass them down to younger generations, but Breck said tutoring centers should be held to higher standards.

The Falcon spoke to Spotlight a year ago about these accounts, and owner Anne Yu’s perspective is represented here. (When approached more recently, Spotlight declined to comment).

Yu said that the center structures its classes so they are geared to specific SHS teachers as a way of helping students. For example, she explained, there are three SHS teachers for Chemistry Honors, and each teaches different material at a different pace, which is why students in the same class are grouped together.

“Actually, from a business perspective, it’s a very stupid way of doing business,” Yu said. “It’s the best way to help you to get the best grade you can.”

In regards to acquiring and sharing old quizzes, Yu initially denied the practice, stating that Spotlight has no means to acquire quizzes. However, when prodded, she said that Spotlight has “very old quizzes,” and that she “did not know” how many exactly. Yu said that unless the teacher or student specifies otherwise, Spotlight can share quizzes that students bring to them.

“If a student comes to us and says they have a problem on this question, are we going to help them or we not going to help them? We make a copy of the problem set,” Yu said. “If the student says that we cannot share this and we share it, then it is our problem.”

Yu added that it is the teacher’s responsibility to make it clear to students that they are not allowed to share quizzes.

“If the teacher doesn’t want the student to use a quiz [she gave back], why does the teacher give back to the students?” Yu said. “If today the teacher gave back the quiz and says that you cannot share the quiz with anybody or anything, then that is a different story.”

Yu also mentioned that past quizzes are no different from other forms of practice Spotlight offers because they are “public access.” When a teacher gives a quiz back, the teacher should be responsible for not reusing the problems and should assume that the problems will get out.

“If [the teacher does not specify to not share quiz], that’s like public property,” Yu said. “Just like if you go online and you saw something, you grab it and use it, and there is no confidential mark there. Can they sue you? They cannot. Because it’s public information.”

In a communication received after this article was originally published, Spotlight stated that past quizzes constituted less than two percent of its curriculum, and that Spotlight stopped providing past quizzes to students as of Nov. 1, 2013.

The plight of the teacher

While some students and tutors may see past quizzes as public information, some teachers do not share the same interpretation. It is easy to point fingers at a teacher who reuses questions from old quizzes they have handed back, but math teachers explained that such a seemingly simple fix is not so simple.

Calculus teacher Audrey Warmuth, for example, makes up new quizzes every year and for every class period so that students can take home quizzes without compromising the integrity of the exam.

“People can be really dishonest, which means that every year, I have to make up new quizzes,” Warmuth said. “Clearly, making up quizzes every year takes time, and then you have to make up a key, it’s a lot of work. The thing is, if you give an exam back, it forces you to redo stuff.”

Despite her efforts, Warmuth knows that tutoring centers have files for specific teachers at specific high schools, including herself. She finds these tutoring center quiz banks “incredibly unfair to the students who do not have access to them.”

“If your goal is to get a good grade, then you probably don’t feel like you’re in a moral dilemma,” Warmuth said. “But if your goal is to learn, there is a moral dilemma there, because the grade isn’t reflecting your actual knowledge or your actual ability; it reflects the fact that you’ve seen the questions before and you had the tutor show you how to get the exact correct answers and how to show your work.”

When asked whether she should stop handing back assessments altogether, Warmuth said that even that wouldn’t stop students or tutoring centers from trying to collect questions. Even now she observes students wanting to copy down test problems in order to show their tutor.

Warmuth recalls one time when she caught a student copying down problems (from a test that she didn’t allow students to take home) to share with his tutor. She was extremely upset, saying, “Now my test is also compromised.”

While no students or tutors interviewed for this story have admitted to taking part in acquiring test questions, Warmuth thinks it is happening. Similarly, assistant principal Brian Safine views such a practice as “unauthorized study material” because tests are school property.

Regardless of the type of assessment, Safine voiced concerns about teachers becoming reluctant to hand back exams, undermining the purpose of students learning and growing from the mistakes they make.

“As a school, we want to view assessments as a learning exercise,” Safine said. “We want students to be able to reflect back from an [exam] and use it to help the teachers know how to improve their teaching. If students view tests as a chance to hand it over to a tutor or a friend, then that undercuts what we’re trying to do.”

Troxell was bewildered two years ago to see a “virgin copy” of her quiz in the binder of one of her students. She was even more surprised to see that there were no student markings on the quiz.

“Someone had taken the time to white out all of the work and make this look as if they had come up with it,” Troxell said, with wide-open eyes, flabbergasted. “But gee … it looks like exactly the same font and exactly the same spacing and exactly my same little answer box as mine!”

She continued: “So either they hacked into my computer and got the original, which they didn’t, or they took the time — and that would have been a lot of time — to make it look like they had developed it, so that is completely dishonest on their part.”

Not only is it “dishonest,” according to Troxell, she also blames tutoring companies for stealing her “intellectual property.” Comparing a quiz to an unpatented computer code, Troxell said she does not consider the quizzes handed out to students to be in the public domain.

“The purpose of giving back a quiz to students is for them to use it to study for the test,” Troxell said. “It is intellectual property. I don’t make the quizzes so that the tutoring company will have an easier time tailoring their course because a student has me as a teacher.”

Moreover, Troxell found the whole practice unnecessary given that teachers get most of their quiz questions directly from the homework, making it the best study material.

“Not 100 percent … but most of the test questions come from the homework,” Troxell said. “So if a student does the homework, either they’ve seen that exact question already or something remarkably similar.”

Nevertheless, Troxell tries her best to change quizzes every year, even though there is not much she can do to make them vastly different.

“Anything we give back, we have different [versions] the next year,” Troxell said, “but there’s only so many ways you can ask how to shift a quadratic [equation].”

The AP Physics controversy

The issue of tutoring and public access gained special attention last year when AP physics teacher Kirk Davis discovered that many of his students had access to his test problems. All the most popular problems from past AP tests since 1988 were compiled in a PDF document titled “Flipped AP Physics,” available free on the Internet. As soon as he found out, Davis re-wrote his tests to exclude past AP problems.

“I have to assume some of the blame because I didn’t know someone had put something like that out there,” Davis said. “And I was using these questions with the intent of giving [students] some experience with questions very much like what [students] will see in May.”

According to an alumnus who requested to be anonymous and who went to Spotlight for AP physics last year as a senior, students tutored by Chung were assigned problems from the document, some of which would appear on Davis’s tests. Other students found the document from a simple Google search. Either way, Davis felt the students with access to it gained an unfair advantage.

“You’re interested in keeping your sanity, getting four hours of sleep instead of two, you are going to cut corners when you can,” Davis said. “Man, if you found a way to reduce study time to one hour, what a winner, and are you going to share that with anybody? No because the curve changes … that’s cheating.”

In regards to the role of tutoring companies, Davis felt that the students deserved the blame for not informing him about the similarity between the problems they were being assigned and his own test problems.

“You can’t tell a tutoring company how to do their business. It’s not their fault, absolutely not,” Davis said. “But the kid should feel a little angel on his shoulder saying, ‘You should go tell Mr. Davis.’”

When the alumnus discovered the commonalities between Chung’s practice test and Davis’s test, he was surprised, but like Breck, did not tell Davis or Chung.

“I didn’t find it a big deal. I was doing college apps, everything was so stressful, it didn’t come to my mind that I was doing anything wrong,” the graduate said. “If [Davis] wanted to test something, I assumed he would make his own problems.”

The alumnus felt that because the study material was found online — it was one of the first sites to pop up when searching “AP Physics practice problems” — all students had access and therefore could choose what to study for the exam. If it happens that the material studied appears on the test, he said, the student should not be accused of cheating.

The alumnus himself did College Board practice tests and thus was aware of some of the problems on the tests already.

“Did that give [me] a leg up? I don’t see anything wrong with it,” he said. “Davis is fully aware that it is on College Board. He admitted it to the class that all these problems are old AP test problems. And he thinks it’s good practice to do those problems, so I did it.”

Furthermore, the alumnus does not believe Chung should be blamed for assigning his students those practice problems because he had no way of knowing what was on Davis’s test. The “Flipped AP Physics” resource consists of 40 questions per chapter, and Chung picked about 15 of them for his students to do in order to simulate a real test. The alumnus said that Chung chose what he thought were the most popular or challenging problems, and it happened that Davis also chose many of these problems for his test.

“Chung’s doing what he can as a tutor,” the alumnus said. “These questions are designed to teach you physics, so why would Chung pick problems he knows aren’t going to be on Davis’s tests if they aren't going to be as helpful in the real world?”

In the end, the alumnus does not think anyone is really to blame and that the whole incident was just one unfortunate coincidence.

“Chung’s not catering to help us cheat; he’s catering to teach us physics,” he said. “Davis is doing the exact same thing.”

The Competitive Edge: Where does the ‘cheating’ line lie?

Academic integrity has been a challenge as long as there have been grades and with it, competition. Today, the precautions against cheating are many: academic integrity lectures, color-coded tests, a spread-out seating arrangement during assessments. But Troxell recalls a time when the issue was not so heavily scrutinized as it is today.

Several years ago, all assessments, quizzes and tests were handed back to students to learn from and go over, and there were fewer barriers to cheating. But eventually the inevitable happened.

“We first started keeping tests many years ago when literally we saw a student of a previous calculus teacher who had his 10 previous tests from the past 10 years. I was like ‘WHAT?!’” Troxell said. “We were so surprised and mortified.”

After recovering from the initial shock, Troxell and the rest of the math department decided to stop handing back tests for students to keep. But, in recent years, Troxell now stumbles upon not past tests, but instead past quizzes, in the hands of her students.

“It’s funny because the rest of the community seems to be asking why we are not giving back quizzes and tests,” Troxell said. “It’s just disheartening, that somebody else found a way not to be really cheating, but another way to sharpen their elbows, to get ahead of the other students.”

Troxell and other math teachers have been making an extra effort to create an equal playing field among students, even if it means having to create multiple versions of the same quiz for different class periods and different years.

“We are not naïve,” she said. “We are hopeful that people will make good, ethical decisions. We have faith that a lot of kids are, but we realistically make three or four versions of the same exam because we know this kind of stuff goes on.”

Breck said that a possible solution is not giving students back quizzes at all, and instead setting up certain periods of time for students to come into the classroom to review them, but even this approach might not be foolproof.

“I think inevitably, students can memorize questions and they write them down and they tell their friends who want to know what was on the test,” Breck said. “So you can’t avoid that because it is in their memory.”

Still, creating multiple versions of the same exam is similar to putting a bandage over a wound. It may reduce the possibility of cheating for the time being, but according to Breck, solving the root of the problem requires a deeper examination of school culture. In order to succeed, Breck said students must “get an edge over the subject,” which, in some cases, comes in the form of tutoring centers.

“Tutoring has had such a big impact on this community, and there are so many ways to get around test taking and that’s just one ploy to do it,” Breck said. “Voicing this right here, people might take note of it, but ultimately nothing is going to change tutoring ways. It may be morally wrong, but people are still going to do it.”

Troxell remains hopeful that students and their parents will make the right decisions.

“I think it all boils down to people can choose who they want to be,” Troxell said. “They can be a dishonest person, get ahead, sharpen their elbows and push everyone away, or they can be an honest person … And that decision is up to every person.”