The early 1970s were tumultuous times in South Vietnam, as Suong Nguyen remembers well. North Vietnam was seeking to gain control of the South to impose its communist rule over it. Nguyen, a little girl then, recalls air strikes piercing the twilight calm over Cam Ranh Bay in South Vietnam. The country was in the midst of the Vietnam war.

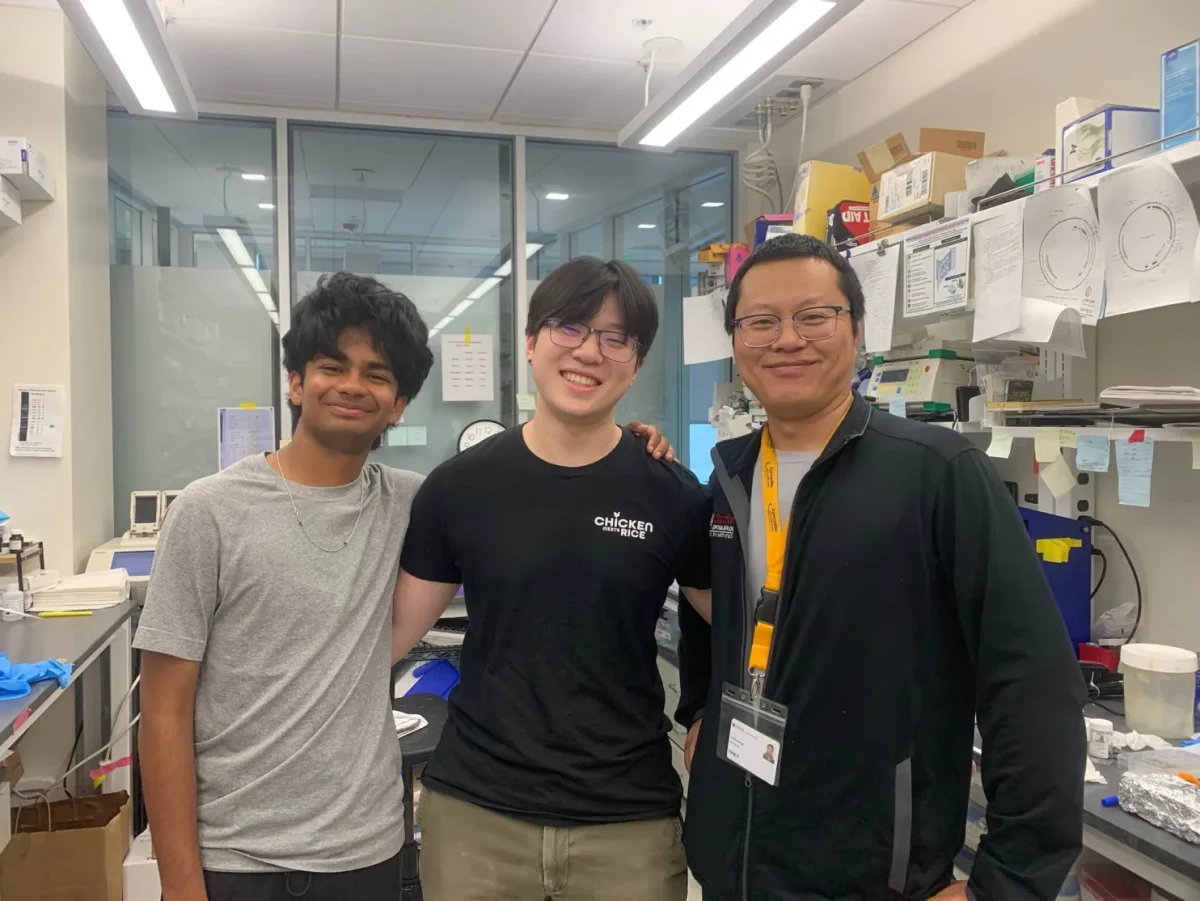

Almost 40 years later, in a country 7,000 miles away, a 16-year-old boy steps out of his Saratoga High classroom with a smile on his face. He is sophomore Quan Vandinh, the son of the same little girl who watched her country mired in conflict.

Quan’s family history is riddled with hardship. Quan’s mother and grandparents faced a tough life in Vietnam. Quan’s maternal grandfather was a jewelry maker, while his maternal grandmother was a seamstress.

After they were married, they opened a dry cleaning business and a jewelry store, which flourished until the mid-1970s.

In 1975, the Viet Cong, the army of North Vietnam, overran South Vietnam and imposed communism throughout the country. For Quan’s family, circumstances took a sharp turn for the worse. During the time in which South Vietnam was still an independent country, Quan’s grandfather had done business with the U.S. Navy. For this reason, when the new government took over, it threw Quan’s grandfather into prison without trial.

“[They] closed all [my parents’] businesses, confiscated their property and sent my dad to re-education camp in horrendous conditions for several years,” Suong said.

When Quan’s grandfather was finally released, Suong said, he began working as a fisherman, looking for ways to escape from Vietnam. He eventually succeeded.

In 1982, Suong and her parents left Vietnam on a small wooden boat. They were among the so-called boat people who fled Communist rule.

After an entire week at sea, they found refuge in Malaysia, a country that lies about 500 miles away, across the South China Sea. They thereupon went by plane to the Philippines, enroute to the United States. A Catholic church sponsored the family’s immigration.

The family’s dream to come to the U.S. was finally realized when they landed in Phoenix on Thanksgiving Day in 1983.

In Phoenix, Suong’s father found a job as an assembler. He gradually paid back the money that the Catholic Church had given his family.

But Phoenix proved to be a bad fit for Suong and her parents.

“[I felt discriminated against] in Phoenix. In 1984, my parents moved the whole family to San Jose,” Suong said.

To their delight, Silicon Valley was far more accepting of them. Soon after the family arrived, Suong started studying at Mission College.

Suong’s parents didn’t have the opportunity to receive an education, which motivated Suong “to finish college and … be the best that [she] could be.”

While the family was comfortable in Silicon Valley, Suong still faced a language barrier. At Mission College, she struggled to communicate with her classmates. When Suong was greeted with a friendly “Hello” from a classmate, she would have to search her Vietnamese-English pocket dictionary for a response.

“You can imagine how long it would take me just to talk about the nice weather!” Suong said.

Although Suong gradually acquired a sufficient command of English to get by, she said that she did not “feel American” for five more years, until she became a U.S. citizen.

In 1993, Suong married Long Vandinh, a mechanic. They had two sons, Trung and Quan Vandinh. Unfortunately, seven years later, in 2000, Long passed away.

Today, Suong feels that the hardship she faced both in Vietnam and here has made her “appreciate everything [they] have right now.”

“I hope to pass that feeling on to my two sons,” Suong said.

Although Quan’s mother suffered the effects of a communist government, Quan is not resentful.

“I don’t blame the people of Vietnam or the country or the Communists at all [for what happened],” Quan said. “It’s not communism. It’s just human nature. The concept of communism is perfect but the idea that it can be used on human beings is ridiculous.”

Quan feels that his family’s history is an integral part of his identity.

“When I was little, I didn't really care,” Quan said. “But I feel now that my background makes me who I am.”

Quan said that the obstacles his mother overcame “represent the struggle to achieve the best for [his family] and the best for the next generation.”

Suong moved from San Jose to Saratoga three years ago so that her sons could “attend one of the best high schools in California.”

“This city has a very small-town feel and is peaceful compared to San Jose,” Suong said. “The boys can walk to and from school safely when I'm tied up with work.”

Although the Vandinhs like the U.S. very much, Vietnamese culture retains a strong influence in the Vandinh household.

The family loves to eat Vietnamese food, such as chicken noodles, broken rice and sweet drinks—all reminders of a country they left behind but still feel connected to.

“I am proud to be Vietnamese,” Quan said.