“To be, or not to be, that is the question: whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing end them?”

Every English 11 student reads these famous words spoken by Shakespeare’s character Hamlet. For many students, the meaning of this passage is fairly clear; others, however, struggle, unable to analyze passages quickly or comfortably.

When it comes to assigned reading, the disparity between the best and not-as-great readers can cause difficulties for English teachers who teach all these students together in one class.

“There are some people who are avid readers, and some people who are much more math-science oriented and would rather not read for pleasure,” English 10 and 11 Honors teacher Amy Keys said. “As for the kids who read for pleasure, reading in-class comes more easily to them.”

Because there are no English honors classes available to them, the range of reading levels grows even larger for freshman and sophomore classes. To effectively teach such wide varieties of students, different teachers use different methods to guarantee every students’ full understanding of a reading.

Keys said that she tries to develop a “sense of contextual understanding,” such as the history behind the reading or the author’s purpose in writing the book. By doing this, students start the novel with some understanding, and the reading isn’t “just a bunch of words on a page.”

If the class is reading something difficult, Keys breaks down and deconstructs the language together with her students. With her document camera, she models different examples of text, and students use colored pencils to color code any patterns or connections they notice within the text.

“My sense is that [students] understand better when they can interact with the text and write on it themselves,” Keys said.

Some teachers ask discussion questions and have students respond to their readings in journals. Sophomore Anish Ramanadham usually does not find comprehending the reading difficult, but when he encounters something unclear and cannot decipher it himself, the in-class discussions led by teachers help clear confusion.

“When I don’t understand something, I will re-read the passage a couple times and try to figure out which words don’t make sense to me, or ask my teacher,” Ramanadham said. “During class, teachers are helpful in explaining the hard-to-read parts of the text.”

English 9 MAP and 12 teacher Sariah Tolley said that she requires her students to summarize the story aloud to a partner, and in the case of Shakespeare and other difficult texts, section by section.

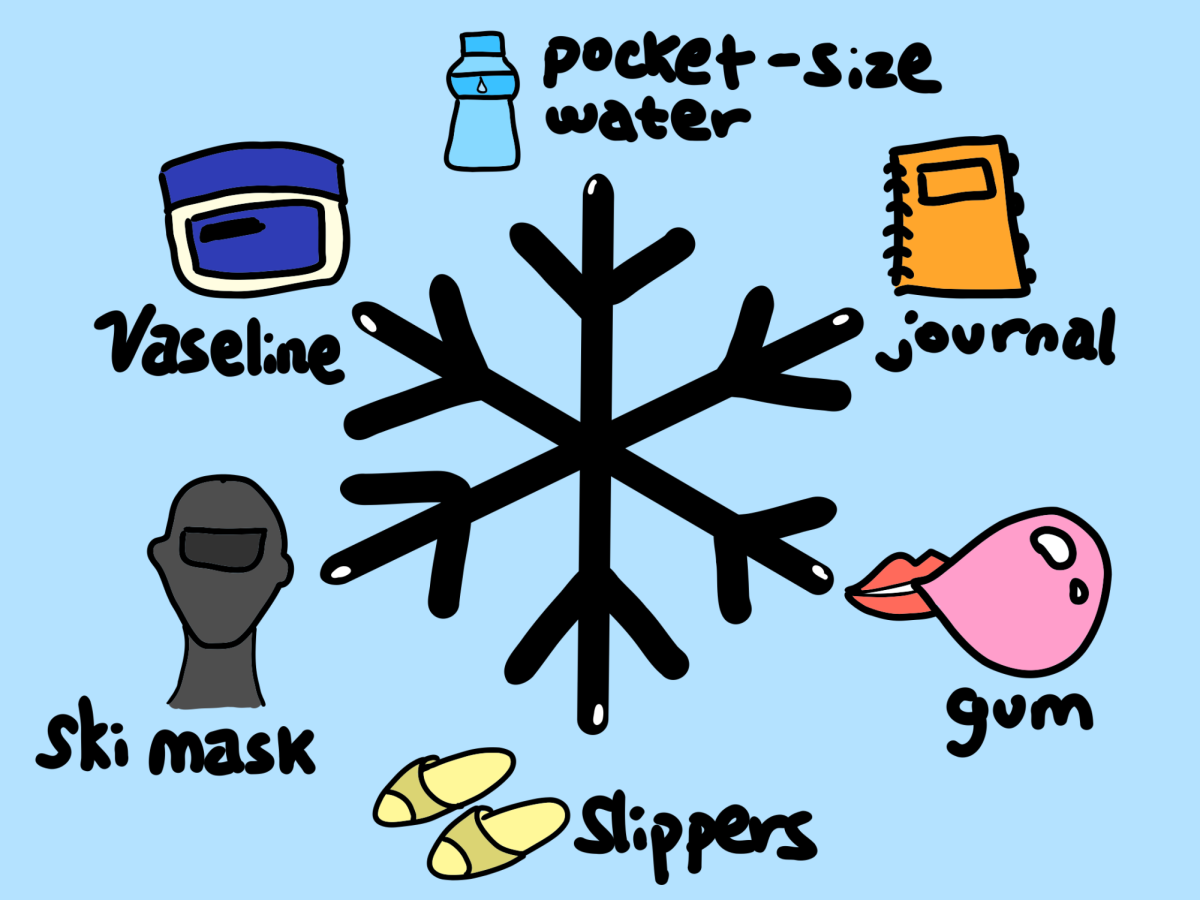

“Other things that have helped include study guides to lead them through a text, and even previewing a tough text before reading so that they start the reading process with key ideas in mind that they then look for,” Tolley said.

Tolley said that she makes adjustments to assignments to meet her students' needs on a regular basis. She also meets with her students one-on-one to figure out ways to help each student reach his or her potential.

While there are many students at lower reading levels, teachers are still surprised by some of their other students who exceed above and beyond in their reading skills.

“I have some great readers who have impressed me from how quickly they can pick up a theme, or notice interesting elements of style,” Keys said.

Although having a large variety of reading levels is tough enough, an even greater struggle for teachers is having students who are learning how to speak, read and write English.

“[These students] are in the process of learning the language while trying to succeed in a class that requires language proficiency, which is such a challenge,” Tolley said.

Even with the trouble that comes with teaching such a wide array of reading levels in the classroom, Tolley is glad to have the opportunity to spread a love of reading.

“It is definitely a challenge, but this is what teaching is all about.”