Junior Jason Li's passion for judo began on a dark night 11 years ago. Weidong Li, his father, was hastily walking through the ramshackle streets of inner-city San Jose.

Mr. Li had missed his bus, and he was worried. There was no one else on the street.

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw a group of men approaching him. His heart raced. Before he knew it, he was surrounded. The men shoved Mr. Li to the ground and tried to take his bag. Mr. Li struggled to hold onto his bag, but he was overpowered and the bag (which contained presents for Jason) was stolen.

The men proceeded to kick him and beat him with sticks. When they were done, they left him half-dead on the street, lying in a puddle of his own blood.

The attackers were never caught.

Today, Mr. Li has a limp arm and cannot walk for more than 15 minutes at a time. However, he was not bitter, and never sought revenge.

Years later, Jason Li described the “traumatizing” sight of his father’s face after the attack as the reason he started judo.

“[My father would] always tell me that if I become as big and strong as those who sent him into the hospital, I should only use my strength to protect others,” he said. “My father’s accident taught me that I should not take anything for granted.”

Over the next decade, Li became a three-time national champion. That success, however, did not last because of a serious injury, one so damaging that Li described it as the end of a dream.

"The sky came crashing down," he said.

Childhood: The beginnings of a top judoka

Born in Shijiazhuang, China, Jason Li came to America when he was 4, only a few months before his father was attacked.

At first, judo did not come easily to him. After the first few practices, he had been thrown more times than he had fallen when he was first learning to walk.

“Although 5-year-olds can’t do much to each other, it still hurt,” he said.

And before he knew it, his parents talked to his coaches and said Li was “too nice for a sport like judo.” So Li quit, thinking he wasn’t made for the sport. Even today, after all his successes, Li thinks about the first time he quit judo. Remembering all the pain the sport later brought him, he said, “Sometimes, I wish I had just stopped there.”

A few weeks after his first attempt at the sport, Li watched a judo video online. He was inspired by the epic throws and the upbeat background music, but what really caught his attention were the expressions of the champions as they achieved their lifelong dreams.

“I wanted that,” he said. “I wanted to be able to throw my arms up and cry in victory.”

And it was then that Li decided that he couldn’t quit. In his return at his first judo tournament, Li thought he would do well. Instead, he lost all six of his matches.

“I cried that evening and listened to my mom tell me that winning was not all that mattered,” he said. “It was something I would hear again and again over the next 10 years, but something I would never accept.”

He kept losing.

“Loss after loss after loss … I became terrified of competition,” Li said. “It almost became a routine. Go on the mat, fall, walk off, cry, and repeat until everyone in my division had beaten up on me.”

At the Palo Alto Invitational, Li, then 6, lost all his matches. As he walked off the mat with tears swelling up, his coach kneeled down and grabbed Li’s shoulders. The coach told him firmly to stop crying, saying, “Big girls don’t cry.”

“Just the shock and strength of his grip were enough to throw off my tears, but what he said brought them back,” Li said. “Back then, it was the most inspiring thing I had ever heard.”

So in 2005, after about four years of losing in competitive judo, Li set himself a goal that seemed ridiculous at the time.

“I was done with giving other people the spotlight and the podium. I was done crying,” he said. “I made it my goal to pursue judo until I had won the Olympics.”

Keeping his word

With the losses at the Palo Alto Invitational still fresh in his memory, Li was determined to get better. Now a scrawny 9-year-old, Li started to work out every day. He ran every morning before school. He beat up on his homemade punching bag to build stamina. He practiced his technique at night.

Li often went to bed thinking of new strategies for matches. He tried to pour every ounce of energy he had into judo.

“My coach once said the only way to become the best is to train when others are training, and train when others are not training,” Li said. “My passion for judo grew out of those long sessions of work.”

Every morning over the summer, his coach woke him at 6, sent him to run in the morning, do weight training before lunch, perform yoga after lunch and finally practice in the afternoon. He trained relentlessly for a month.

“I was pumped. Everything about it was unbelievable,” he said.

Li’s “rebirth” had a huge impact on his performance. Now 10, Li received a bronze medal at the California State Championships. He won gold at two more state championships in the following years, making him the top judoka (the name for judo athletes) in California.

Li wasn’t done. In 2008, Li entered his first national tournament.

“I was ready to become the national champion,” he said.

The national championships that year took place in Boston. Li’s division had 34 competitors and was double-elimination style.

Li had trained hard to get onto the national stage—and he had made promises to his friends and family back home that he would win. He knew that if he wanted to become an Olympian, he had to win nationals. Here, he had his first chance to vindicate himself, to prove that his hard work was not in vain. His seemingly ridiculous goal now seemed slightly more realistic.

“The day of the competition, my heart hammered against my chest and my whole body shook,” Li said.

The national stage

Li lost both matches. They weren’t even close.

“I will never ever forget the terrible losses that weekend,” he said. “It was as if my dreams were shattered. My training, my suffering, my journey … it was all for nothing.

“Although I was composed within the arena, I broke down that evening. I knew I had to accept that I did not win despite my hard work and effort.”

The day he flew home, his judo coach called him. Expecting a lecture on how all winners start with failure, Li was instead offered a second chance. Li had forgotten that a second National Championship was held only a month later.

“I couldn’t believe my ears,” Li said.

Li’s coach had already registered him and booked hotels for the National Championship in Fresno. With a month to train for Fresno, Li was under an intensive schedule. He was determined to make his second chance count.

“I can tell you about how hard I trained and all the blood, sweat and tears I went through, but without ‘Eye of The Tiger’ playing, it wouldn’t be all that exciting,” he said.

What was truly significant that summer was not how much he practiced, but how much weight he lost. In order to compete in a lower division, Li lost 21 pounds in the course of three weeks. His parents strongly advised against it, but Li knew it was necessary for him to win at nationals. Little did he know that the very determination that led him to victory would later be his downfall.

“That was the summer I stopped caring about my body,” he admitted.

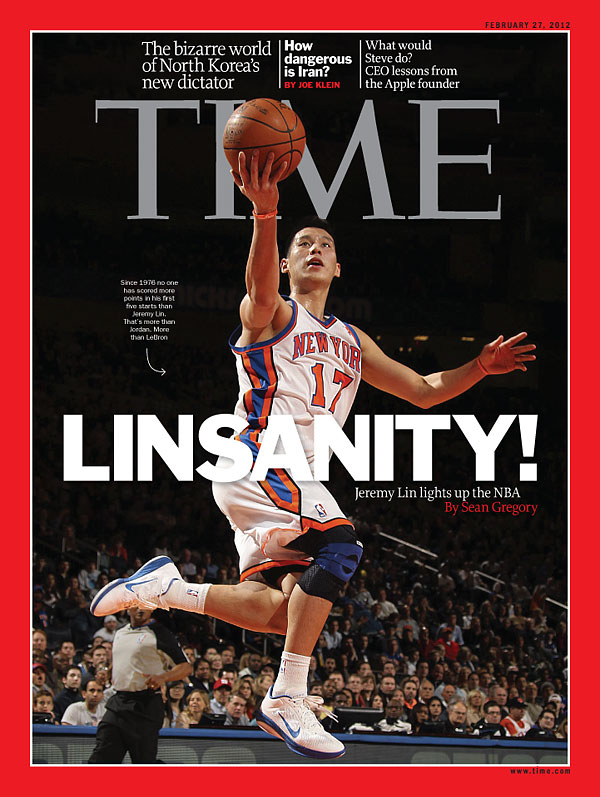

The training paid off, and Li ascended toward the apex of his judo career. He won the national tournament in Fresno in 2008, and he didn’t lose a match again for two years. At large national tournaments, he rode the dark horse and worked his way up to the top podium. At small tournaments, he was able to experiment new techniques and coach younger kids between my matches.

No longer the boy who walked off the mat crying loss after loss, Li had taken over four national medals and was a three-time national champion—not to mention that he had gone undefeated for two years.

The “big girl” had become one of the best in the nation.

On the Road to the Olympics

By now, it was 2009, and Li had everything except recognition from the United States Judo Federation.

But as soon as his mother had begun her “many lectures on being humble and modest,” Li was asked to join the National Team to travel and represent U.S. across the world. This was Li’s door to the World Championships and possibly the Olympics.

Li wrote of the moment, "I fumbled with the letter and tore it open. 'You are the nation’s potential in judo,' the letter read. I took two steps, pinched myself and sprinted out of the house.

"It was a top honor—only 18 individuals across America could join the team," he explained. "It had been my holy grail. To me, a spot on the development team was worth infinite medals and trophies—except one, that is. The Olympic Gold."

However, the letter also marked the start of his downfall. The state championships that year was held in San Francisco; it was the very first tournament Li’s mother went to see, since she had always feared to see him fight and get injured before her eyes. Tragically, her very fears came true.

In a 23-man division, Li fought his way up to the finals with ease. One of his best friends, also a former national champion in the weight division Li had dropped into, worked his way up to the final bracket as well. Li had long idolized him.

“I looked up to him for all of my judo career, and this was my first chance of rivaling him in the main event,” Li said. “I wanted to prove that I was no longer the ragdoll that was tossed around in practice every day.”

Li and his friend’s match for the State Gold continued until double overtime.

“They say that when a strong judoka fights a weak one, the match ends quickly,” Li said. “But when two strong judokas fight, one is meant to die.”

With only 6 seconds to go, Li attempted a final throw. It was countered, and he was sent flying. While in mid-air, Li managed to turn his back so he wouldn’t land on it. Instead, however, Li hit the mat head-first and hurt his neck. Before the buzzer sounded to end the match, Li was rushed to the hospital.

With a forfeited match, Li’s two-year streak of gold medals was over. In the long recuperation process, Li’s doctor banned both physical and mental exercise—even difficult math problems were not allowed. However, Li ignored all restrictions and continued to his sport. Nationals were coming up soon.

“People told me that injuries, if not completely healed, lead to more injuries,” he said. “I got to experience it first hand.”

At nationals in his freshman year, Li tore his knee ligament. However, he continued to fight through excruciating pain. Li lost his title and had to settle for bronze. It turned out to be his last competition.

“One night, I wet myself”

After an MRI scan and several trips to multiple doctors, doctors told Li he needed back surgery. His spine had become distorted from years of judo, wrestling and weightlifting. Problems with his nerves, including a herniated disk, caused him to have trouble walking. Still, Li refused surgery, thinking he didn’t need it.

Then, one night in his freshman year, he wet himself.

“I woke up embarrassed, but quickly realized I was in trouble,” Li said. “I felt excruciating pain in my back and my legs couldn’t move.”

Li dialed 911 on his phone and nonchalantly said, “Yeah, I’m kind of paralyzed and my legs stopped working. Can I get an ambulance, please?”

Despite the pain, Li managed to laugh.

“I remember telling my [7-year-old] sister who had woken up, ‘Jennifer, if you want to hit me, hit my legs now. Because I can't feel a thing!’ ” Li joked.

After fighting and winning matches with broken fingers, broken toes and even a torn ligament, Li did not fear physical pain.

After he was rushed to the hospital, Li learned that connection with the nerves of his lower body had been cut off by his spine’s mutation. He had lost all sensation below his waist, causing him to lose control of his bladder. Within 30 minutes, he was pushed into the emergency operating room. With a broken back, Li’s career was over.

Still, Li met the diagnosis with skepticism.

“I tried to convince myself that I would become the superhero who disappears for months and then returns to demolish his enemies,” Li said. “I thought I was some sort of Dark Knight.”

As Li relearned how to stand, how to sit, how to walk and how to function normally, he still could not allow himself to accept that his competitive Judo career was finished.

“I joked around with my mother saying this injury is just like any other booboo I’ve had,” he said. “Grinning ear to ear in my hospital gown, I told my mom that I was going to pop back up in weeks and return to the mat and take back my gold medal.”

But as Li spoke with such energy, his mother started crying. His mother, distraught asked him why he was harming himself. She asked, Do you know how much it hurts to see your child fall paralyzed at only 14 years old?

“And with that, I finally realized I was hurting those around me, not just myself,” he said. “The only thing I could say to my mom was ‘I’m sorry, I’ll stop.’”

Li’s spine injury had left him paralyzed from the waist down for two weeks. It took another month to learn how to walk and another four months to run. This was no bump on the road to success—it was a dead end.

“I had poured my life into judo,” Li said. “And to have it all come crashing down on me hurt more than any broken bone. No one knew the way I coveted being a winner. No one knew how traumatized I was by my father’s face after his incident nor understood how I was bullied in elementary and middle school.

“My coaches knew me as the kid who was once ‘too nice,’ but I had finally found comfort in my judo gi [a traditional judo uniform], stepping on the tatami mat. I was boastful and cocky at tournaments because judo was all I that I was proud of.”

Life without sports

Li is forever unable to play contact sports. He can no longer perform strenuous activities, his leg will never fully recover, and his broken jaw from a judo accident will never be fixed.

“Judo is over for me, but its values I will never forget,” he said. “The medals, the awards … I realize that they are worthless in comparison to the intangibles I gained from judo.”

So Li put his 85 medals and 32 trophies in boxes and donated them all to his judo club to award future students.

Instead, he kept the intangible lessons the sport taught him—strength, determination and “the true meaning of character.”

“Winning is not about the number of medals sitting on your counter, winning is the pure exhaustion at the end of the workout,” he said. “Winning is pushing aside pain to fight, and most importantly, winning is realizing what is important in life—and what is not. I wanted to be a World Champion, but now I realize the world is bigger than 100 square meters of tatami mat.”

Today, Li’s acceptance letter for the national team is long expired. His judo uniform gathers dust in his closet. The last time he touched judo was when he threw his friend junior Bryan Chow for a photoshoot.

Li has since found interests elsewhere: He owns two startup companies. One of them, iReTron, has been featured in the San Francisco Chronicle and FOX News and has won Li $6,000 from various contests and grants. Li also loves slam poetry and playing the piano, and is the head photographer for Yearbook. He has become a part-time judo coach.

“I may only have had 10 years in the sport, but those years were packed with enough stories and morals to last a lifetime,” he said.

Although his judo career and his Olympic dream may be over, Li still maintains his determination and self-confidence.

“I’m only 15 years old. I’m barely 20 percent done with my projected lifespan,” he said. “When I received the invitation from the national judo developmental team, I told myself that not even the sky could limit me. I still believe in what I said.”