In November 2019, when the first known case of COVID-19 was reported in Wuhan, China, the world was totally normal. In schools like Saratoga High, pencils scratched against paper, friends whispered jokes in class and sighs of exhaustion filled classrooms after every test. As the calendar turned to 2020, only a few paid attention to headlines about the emerging virus — and most dismissed them as another piece of distant news, irrelevant to the daily struggles of student life.

But by March 13, everything had changed. Desks were left empty, screens replaced chalkboards and gossip during school faded into silence. What started as an ordinary school year quickly turned into a crisis for educators, affecting 1.6 billion students around the world.

COVID-19-era had a profound impact on education that continues five years later. The abrupt shift to virtual learning challenged both students and teachers, drastically decreased instructional time and hindered student understanding.

Math teacher PJ Yim said, “Teachers were overwhelmed by all the things going on. Some wanted to just get through the year and let the petrifying times pass by.”

In years since, one of the results of the shift was unprecedented learning loss, doing significant damage to national academic standards. Take mathematics and reading scores, for example: The Associated Press has written that students in the U.S. consistently scored 5-9% worse on math and reading after the year plus in virtual learning, the largest decline in 30 years.

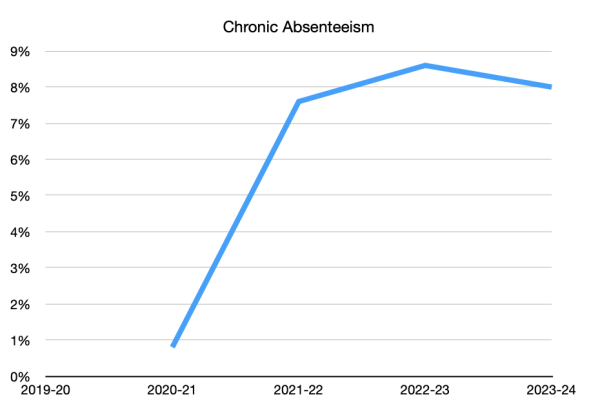

Beyond academics, the pandemic reshaped the culture surrounding education too. The New York Times said absenteeism rates — the number of students missing a significant number of days from school — have skyrocketed to 28% since schools returned from virtual learning, as students have struggled to re-engage with in-person learning.

In response, schools and governments initiated educational recovery solutions by implementing tutoring and summer programs, adjusting course placement policies and increasing federal funding for academic support. While these efforts aim to patch the learning loss, one question remains: How long will the effects of the pandemic linger, and what further initiatives and steps are necessary to ensure students return to their pre-pandemic academic standards?

Learning recovery varies significantly across the nation

While schools have returned to pre-pandemic in-person operations, students aren’t reaching the same levels as before 2020.

According to Stanford and Harvard University researchers, as of the 2024 grading period, the average U.S. student’s performance lagged nearly half a grade level behind pre-pandemic achievement — 0.46 grade levels lower in math and 0.47 in reading.

The severity of learning loss, along with recovery rate, also vary across the country — differences in political ideology between Democrats and Republicans on managing schools during the pandemic eventually led to a wide disparity between red and blue states.

Data from Burbio, a data service analyzing school policies across the nation, indicates that red states followed comparably lax policies emphasizing freedom and local choice, while blue states enforced stricter state-level mandates. Red states like Florida, Texas and South Dakota allowed districts to reopen in the fall of 2020, months before blue states like California, Illinois and New York. Between September 2020 and May 2021, red states gave students more than double the hours of in-person learning, which ultimately softened the impact of learning loss.

A study examining student performance data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) confirms this trend — while reading and math scores dropped nationwide, blue states and swing states saw a much steeper decline compared to red states.

Within states, socioeconomic status has also been a key factor in determining student outcomes. Take Alabama, for example — it’s the only state where average student achievement has bounced back above pre-pandemic levels.

According to the U.S. government platform DATAUSA, high poverty districts in Alabama, such as Montgomery, Mobile and Birmingham, had less than half the average household income of higher income districts like Shelby County; these districts, lost more than half a grade level in learning outcomes, while higher income districts saw little to no impact in achievement. Some schools with greater average income even saw improved academic outcomes over the course of the pandemic.

Research reveals the leading cause of this trend to be the “digital divide.” According to ACT’s Center for Equity in Learning, the digital divide in education is the gap between people who have sufficient knowledge of and access to technology and those who do not. As schools utilize more technology in class, this divide increases, widening the learning gap between students who can afford technology and those who can’t.

To those with an insufficient virtual learning experience, the pandemic fractured trust in an education system that left students with little to no support.

Thus, the rapid transition and high expectations felt upon the return from the pandemic led to a spike in absenteeism.

According to The New York Times, an estimated 26% of public school students were considered chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year — a 15% increase before the pandemic — citing a loss of trust as a main cause.

For example, parents from Texas expressed frustration that their children were left to struggle through online learning with little assistance, only to be expected to perform at their grade level upon returning to in-person classes.

This rise in absenteeism is the leading factor hindering schools’ recovery from pandemic learning loss — teachers are forced to choose between slowing down curriculum or allowing chronically absent students to fall significantly behind, options that both stagnate recovery processes.

Pandemic learning loss has reshaped the college admissions process

As many students struggled to recover from pandemic-related learning loss, their lack of academic proficiency had a significant impact on the college admissions process as well.

In October 2023, the organization behind the ACT standardized test reported that the 1.4 million high school seniors who took the ACT averaged a score of 19.5 out of 36, marking the sixth consecutive year of declining scores. The year before, ACT scores fell from 20.3 to 19.8, dipping below 20 for the first time since 1991.

Perhaps surprisingly, declining ACT scores did not correlate with average GPA — nationwide average GPAs increased by 0.19 between 2010 to 2021, from 3.17 to 3.36, as grade inflation grew.

Due to these contradictory trends, admissions officers felt less confident in previously reliable benchmarks of academic preparedness. Combined with mass cancellations of ACT and SAT exams, several U.S. colleges and universities went “test optional” in 2020, giving applicants the option not to report their standardized test scores.

Although SAT testing resumed in August 2020, many colleges kept their policy changes as they believed that standardized tests could no longer accurately assess student performance, especially since so many students could not take them. By 2023, only 4% of the colleges using the Common Application system required standardized testing. For some, these changes were hailed as a step that could ultimately increase diversity and equality in college admissions.

But this new approach to college admissions struggled to keep up in practice. For instance, admissions officers at Emory University faced challenges on how to assess the college readiness of the Class of ‘24, who started high school virtually, making it almost impossible to measure their learning.

After testing has become more available, Harvard University officials announced last year that they would reinstate standardized testing requirements from the Class of ‘25, just four years after going test optional. The same announcement soon followed for other elite schools, including Stanford and Yale.

As institutions reinstate testing requirements, the future of college admissions may see a recalibration — one that reflects both the lessons learned from adjusting to student conditions due to the pandemic and the enduring need for reliable academic benchmarks.

SHS students continue to feel the lingering impact from the pandemic

The school is known for its academic proficiency, outperforming both state and national averages. In the 2024 California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP), the Class of ‘25 doubled the state averages for English/Language Arts and Mathematics — as a whole, the Los Gatos-Saratoga Union High School District is ranked No. 2 in the state in both areas.

But even though SHS excels in academic achievement, data still confirms that students felt a heavy impact from the pandemic in terms of their learning.

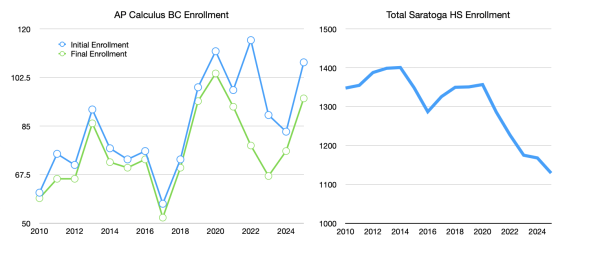

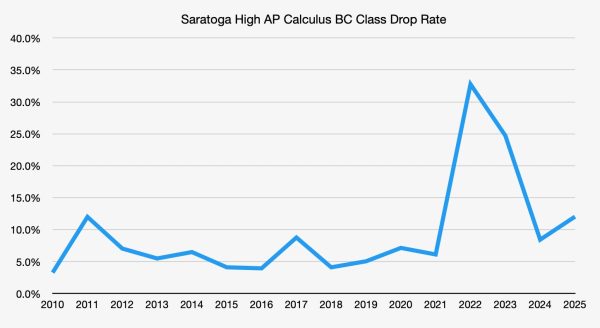

A crucial data point can be seen by examining the drop rate for AP Calculus BC throughout the years, one of the most difficult courses offered at the school.

While sign-ups for the class had been increasing over the past 15 years, initial enrollment of the class peaked at 116 students for the 2021-22 school year, the first year following the lockdown. That school year also saw the most number of students drop the course since 2010 — 38 students, or approximately one third of original enrollment.

Notably, from 2017 to 2022, there was a 103% increase in the number of sign-ups for AP Calculus BC, while the student population declined by 8%.

Yim, who taught the class during these years, recalled that, during virtual learning, teachers struggled to prepare their curriculum online, and in their conversion to the new format, they ended up unable to prioritize the academic rigor.

Yim has also observed that many students have been mistakenly overestimating their math skills and enrolling in courses beyond their actual proficiency, in large part due to online learning offering less rigorous coursework and inflated grades.

“The percentage of students getting an ‘A’ in AP Calculus BC went up [during the pandemic]. Before the course selection, I repeatedly warned students that ‘you may have an ‘A,’ but it’s not a real ‘A,’’” Yim said.

Spanish 3 and AP Spanish teacher Sarah Voorhees also noticed how the pandemic has severely affected students’ academic performance.

“During the pandemic, the only time students ever spoke Spanish was in their Zoom class, and they said one or two words,” Voorhees said. “Most importantly, students cheated by finding the textbook answers on Quizlet and continuously using a translator.”

According to Voorhees, students were able to take tests without notes and receive satisfactory grades, but that’s not the case anymore. She said that the academic standards were lowered during the pandemic and decided to allow open-note and textbook tests upon the students’ return and have continued that practice since. However, she realized students are still struggling.

Matching nationwide trends, chronic absenteeism rates have surged at SHS as well.

The percentage of chronically absent students during virtual learning was only 0.8%. However, by 2022-23, figures from the state’s Department of Education show the percentage rose to 8.6%, increasing over tenfold. The drastic increase suggests that even in high-achieving schools like SHS, the impact of pandemic-related disruptions continues to shape academic performance.

The long road to recovery: ongoing efforts and reforms

With previous national trend data showing the severity of pandemic learning loss, school districts nationwide have been implementing new laws and efforts in an attempt to relieve this issue.

In March 2021, the American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ARP ESSER) gave $122 billion to education agencies across the country to address the repercussions of school closures; local education agencies were required to preserve at least 20% of their funds for combating learning loss.

Additionally, a lawsuit was filed against the state of California by a dozen Californian families, claiming that remote learning was inconsistent and ineffective. Ultimately, lawsuits like these forced the state to spend $2 billion in pandemic relief funds to help students who were most impacted by remote learning recover academically, with measures including tutoring, counseling and after-school activities.

California school districts have also been putting in major efforts. The Compton Unified School District, located in LA, saw its 2023 test scores rise even beyond pre-pandemic levels — the district’s ELA and mathematics grades in CAASPP increased by 8.1% and 15.5%, respectively.

According to their superintendent Darin Brawley, the district accomplished this by using the relief funds to contract multiple tutoring agencies and offer a mental health curriculum.

SHS is also implementing new policies and rules in order to mitigate further learning loss. After 74 students switched math levels this year — compared to 30 last year — the school is implementing a new math placement policy preventing students from advancing through math levels without mastery of previous courses.

Despite poor student achievements in her class, Voorhees believes that students are almost back on track compared to pre-pandemic levels.

“It’s been five years, and although students are used to cheating, it’s getting better and they can speak Spanish more fluently,” Voorhees said.

Now that five years have passed, some pre-pandemic trends have returned to normal.

The AP Calculus BC drop rate, for instance, has evened out to 8.4%, falling from its peak of 33% in the 2021-22 school year.

(Ethan Lee)

While efforts such as tutoring programs, increased federal funding and curriculum adjustments aim to bridge the learning gap, true recovery will require sustained commitment from educators, policymakers and individual communities.

The pandemic has forced a re-evaluation of educational structures. Moving forward, schools will be prioritizing not only academic recovery but also student engagement, mental health support, access to resources and many more factors in an effort to recover from this unprecedented disruption to education.