With the lights off and students gathered around the projector, I remember my fourth-grade class watching a documentary about the life and work of Jane Goodall, the English zoologist and primatologist. We were told about how she had researched chimpanzees in Tanzania for 60 years, how she had practically lived with the chimpanzee family and how she became the most famous animal rights activist of our time. Out of childish innocence, I had wondered why anyone would ever not want to support animal rights; after all, we share the same Earth with animals, and animals are cute, right?

Spoiler alert: That reasoning didn’t even scratch the surface of our human history with animals, much less the broad and controversial realm of the animal rights movement.

As of 2024, an estimated 10 million animals in the U.S. die from human abuse or cruelty annually, and roughly 200 million animals are killed for international human consumption daily. Ninety-nine percent of animals contributing to the meat market are raised on factory farms — where livestock is grown solely for the purpose of human consumption — and over 100 million more are killed in animal testing — where animals are subjected to scientific research experiments.

What I had seen in the documentary all those years ago — Jane Goodall’s natural paradise where chimpanzees and humans lived in peace together — seemed to be hardly relevant to the reality of our supposed peaceful coexistence of humans and animals.

Still, the concept of animal rights goes back thousands of years. Religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism have long since practiced principles of non-cruelty against animals. The first piece of animal protection legislation was passed in 1635 in Ireland. It prohibited citizens from tearing wool off living sheep.

Since then, both religious and secular institutions have slowly added more protective laws for animals, with the first piece of animal welfare legislation passed by a modern representative body “Martin’s Act” in 1822. The act outlined protected cattle from cruelty in the UK. Martin went on to help found the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), the world’s first animal protection organization.

In the 1970s, the fight for animal rights took off exponentially, with governments across the globe implementing several new regulations every year. With the goal of public awareness and the abolition of human activities that cause animal suffering, the animal rights movement reflects a growing ideal in our contemporary world, backed by individuals, governments and independent organizations alike.

Today, most modern societies have evolved to recognize a wide variety of rights and many have overcome grossly unjust wrongs — such as with the abolition of slavery in the U.S. during the Civil War. Similarly, individuals have grown more empathetic toward animals, spurring the emergence of animal rights movements around the world. While our relationship with the animal kingdom is far from perfect, it also has started to lean toward more compassion and care than in past centuries.

For all this progress, studies have shown that the public tends to view vegans and animal activists in a negative light, with some such individuals becoming internet memes, like “That Vegan Teacher,” a controversial social media personality and educator who went viral for promoting veganism, often through provocative and polarizing content. As one of many billions of social media consumers, I have seen for myself the harsh backlash “That Vegan Teacher” received as she gained popularity.

Courtesy of That Vegan Teacher

Internet personality “That Vegan Teacher” acts on controversial views of veganism, accusing Christians of being “fake” for consuming meat.

In addition, the small but outspoken percentage of vegans who are extensively critical or hateful of meat-eaters have only furthered the stereotype of the “annoying vegan” or “over-dramatic activist.”

Despite the stigma surrounding veganism, the number of vegans in the U.S. increased 30-fold between 2004 and 2019, from 290,000 to almost 10 million, according to a study by Ipsos Retail Performance. Since then, numbers have only continued to increase.

These upward hikes can be partially attributed to a rise in public awareness about veganism’s many benefits through social media, the internet and educational systems. However, animal cruelty remains a persistent issue around the world, notably through factory farms and animal testing.

Factory farms are epicenters of harms

With the demand for meat ever-growing, factory farming has become a popularized practice in the food industry. The process involves raising livestock in intensive confinement and is at the center of numerous notorious cases of mass animal maltreatment; for example, hundreds of meat-packing companies have overseas cattle transportation ships with crowded, putrid and unsanitary conditions.

The conditions of one such ship were brought to light in 2021 in Cape Town, South Africa, where a livestock carrier was docked and exposed for its unhygienic cattle conditions and its foul smell that enveloped the town. Carrying a total of 19,000 cows headed to Iraq, the vessel had buildups of feces and ammonia across cramped holding pens where investigating veterinarians found several dead cows and had to euthanize eight more.

Many instances of notorious factory farming also involve octopi. With its high demand in the international seafood market, the octopus farming industry is steadily growing, but running into issues with supply. To resolve this, some companies are attempting to domestically farm and raise octopi for consumption.

However, octopi are considerably more intelligent than conventional farm animals. Well-known for their ability to problem solve and retain long-term memories, octopi are said to be as intelligent as cats and as smart as a 3-year-old child. One study by the non-profit Faunalytics suggests that many believe the treatment of animals should be proportional to their intelligence or sentience: If an animal is able to feel emotions, like pain and pleasure, they should be more protected than animals who don’t understand those emotions.

So far, Washington was the first state to ban octopus farms, with California recently following suit by enacting an even tougher bill last September. California is now also the first state to prohibit sales of farmed octopus.

Animal testing has pros, cons and alternatives

One of the most controversial parts in the animal rights movement is its stance on animal testing — procedures performed on living animals for purposes of scientific or commercial research.

Since 1966, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act, there have been ongoing conflicts between critics of the practice and its many supporters.

Today, most countries still allow animal testing, despite the harm often done to lab animals such as rats and guinea pigs. Although more than 115 million lab animals are used and even killed by experimental inventions each year, the scientific community argues that animal testing is essential for understanding human diseases, biological processes and developing treatments — advancements in science that ultimately save millions of human lives.

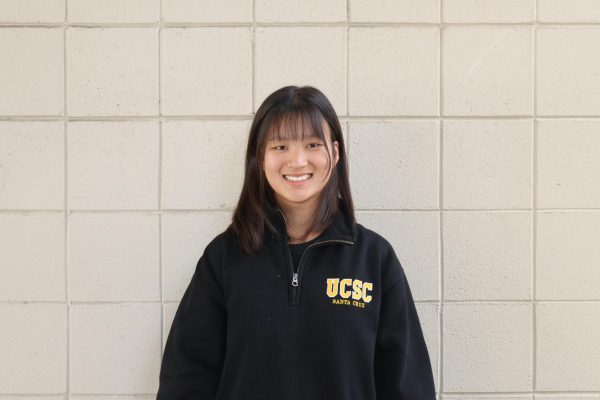

To get some first-hand insight into how the topic of animal testing is received by the scientific community, I reached out to senior Grace Liu, who is the co-founder of iClear, a non-profit aimed at reducing animal testing. She believes the controversy surrounding animal testing is a valid issue in research that should be addressed, even by students.

“I have experience in biology research, [and] there are some aspects of research where it is necessary to use animals to some extent,” she said “But I think the current state of animal testing has a lot of room for improvement in the ethicality of how animals are treated.”

Liu notes that, in fields like neuroscience, animal testing may be the most effective or even necessary for experimentation. Understanding that removing animal testing from the world of scientific research is practically unfeasible, she emphasizes that her work with iClear is only aimed at reducing animal testing, not eliminating it.

Even outside of neuroscience, a prominent example of the benefits of animal testing can be found in the development of the COVID-19 vaccine. Even before the pandemic outbreak, researchers who were working with mRNA vaccines used a variety of animals, ranging from rats to monkeys, to ensure the medicine would work correctly and ease symptoms for human use.

However, another downside of animal testing are the genetic differences between tested animals and humans, which makes successful translation of results and drugs from animals to humans very difficult.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 92% of drugs tested on animals are not deemed safe and effective for human use. This is primarily because other species seldom naturally suffer from the same diseases as found in humans and don’t have the same biological responses to potential medications. In some areas of disease research, overreliance on animal models may instead delay medical progress rather than advance it.

These delays and failed trials are expensive for scientists, making the field of drug development a notoriously long and expensive process, with recent estimates assessing it can take $314 million to $2.8 billion dollars to develop a single new drug.

To combat the inaccuracies and inherent violence of animal testing, scientists have developed more alternatives to animal testing, such as in-vitro cell developments. This alternative involves using microfluidic devices lined with living human cells mimicking the structure and function of organs — called “organs-on-chips” — for experimentation.

Since these models use human cells, they are capable of yielding more accurate results in both disease and drug research, not limited by differences between species. Although organ-on-chip models have higher initial setup costs, their potential for longer-term use and reduced reliance on animal models can prove cheaper. There are already companies who are selling these organs-on-chips to other researchers to use in place of animal tests such as AlveoliX, MIMETAS and Emulate, Inc..

Other alternatives include in-silico — or computer modeling — and human volunteers, who are usually injected with “microdoses” of an experimental drug or tested through a series of MRI scans. It is also possible to use human tissue donations from surgeries such as biopsies, cosmetic surgery and transplants. Using test cell cultures of human tissue instead of live animals and mathematical models for toxicity testing works just as well as animal testing — and has been shown to be much more accurate than animal testing.

Nevertheless, while these methods are arguably more reliable and translatable to humans, they can be limited in fields that require the full biological processes of test subjects. With current technology, the National Institute of Health (NIH) states that alternative approaches cannot accurately replicate or model all the biologic and behavioral aspects of human disease, meaning that animal testing will persist in remaining integral to select areas of scientific research.

In addition, many see animal testing as a far more convenient and familiar method of product assessment, compared to newer technologies.

“Even though I’ve always felt very sympathetic towards animals, once I looked into animal testing more, I realized it’s a lot more nuanced than I thought initially,” Liu said. “With iClear, we’ve talked with people from different countries as well, and that really changed our perspective on how animal testing is around the world.”

Liu notes that historically and culturally, there have been varying perspectives on animals and animal rights, many of which have carried on to our modern age. As a result, she has realized that, when advocating for international policies in favor of animal rights, it is necessary to be considerate of other viewpoints around the world.

On the other hand, animal testing is also widely used in the cosmetics industry, spurring many movements to call for its federal ban. Unlike testing for scientific research and drug development, cosmetics aren’t necessary for human survival or life expectancy extension, while having access to the same animal-friendly alternatives available for medicinal testing. Cruelty Free International, an organization solely focused on ending animal experimentation, argues the use of animal testing in cosmetics industries is far more inexcusable.

Thanks to social media, there have been widespread online campaigns, boycotts and protests against animal tested products, with several companies such as celebrity Kylie Jenner’s Kylie Cosmetics, e.l.f. Cosmetics and Dove opting to go “cruelty-free” and not testing their products on animals.

It’s important to note that, while multitudes of companies jump at the opportunity to appear more ethical than their competitors, the reality of their actual practices is often just as unethical as brands that do not make such claims. The term “cruelty-free” is not clearly defined by law, meaning manufacturers and producers can interpret it however they wish. This blanket term could actually signify that the product was simply tested in a foreign country or an animal was killed for an “animal product” as an ingredient but no testing took place.

For this reason, many countries — including Australia, South Korea and those in the European Union — have banned animal testing for cosmetics. The U.S. still allows this practice, however, and China requires all cosmetic products to be tested on animals before they are allowed in the market.

The animal rights movement focuses on factory farms

Many animal rights activists call for the end of all such examples of animal cruelty — with a primary focus on factory farms. Although there have been significant improvements for animal rights, the Humane Society of the United States argues that existing laws often fail to protect animals adequately. Even today, the AWA’s definition of animals excludes mice, birds, rats and agricultural animals, which are the most heavily exploited in labs and agriculture — protecting less than 90% of animals in the U.S.

It remains a fact that drastic changes are difficult to make because of how deeply rooted some practices — such as factory farming — are in society.

But the protests, boycotts and protections in place through action by the animal rights movement has shifted society toward a heightened awareness of animal cruelty. Thanks to the work of the animal rights movement, it is now a widely accepted belief that animals are sentient beings deserving of respect and care. States around the country have animal welfare laws in place to protect them. New protection laws continue to be introduced, such as California’s Proposition 12, which ensures that livestock are given enough living space to combat overcrowding.

Over the years, the animal rights movement has grown in following and political influence. Despite the controversial public opinion of animal activists, their work continues to give voice to the voiceless and spread awareness to the cruelty that has been normalized all around the world. One day, perhaps young children won’t have to journey all the way to Jane Goodall’s documentary to witness humanity’s cruelty-free coexistence with animals — instead, that vision could be our new normal.