As he shot down a steep mountainside at the 2024 IFSA Kirkwood National Finals, junior Richard Fan took a leap of faith.

Jumping off a cliff and preparing his body for the impact, Fan approached his line confidently but realized mid-air that he was losing control. Overshooting his landing, he tumbled into the snow, skis detaching from his feet, and rolled precariously close to another cliff edge — only to be saved by a collision with a small tree.

Most athletes experience some risk of injury as they train and compete — statistically, high contact sports like American football, boxing and taekwondo, along with rugged, strenuous sports like BMX biking have the highest injury rates.

Yet for some student athletes like Fan, athletics comes with an added factor — regularly facing extreme, unavoidable dangers such as flipping over in packed snow while skiing or falling while performing intricate acrobatics on a balance beam in gymnastics.

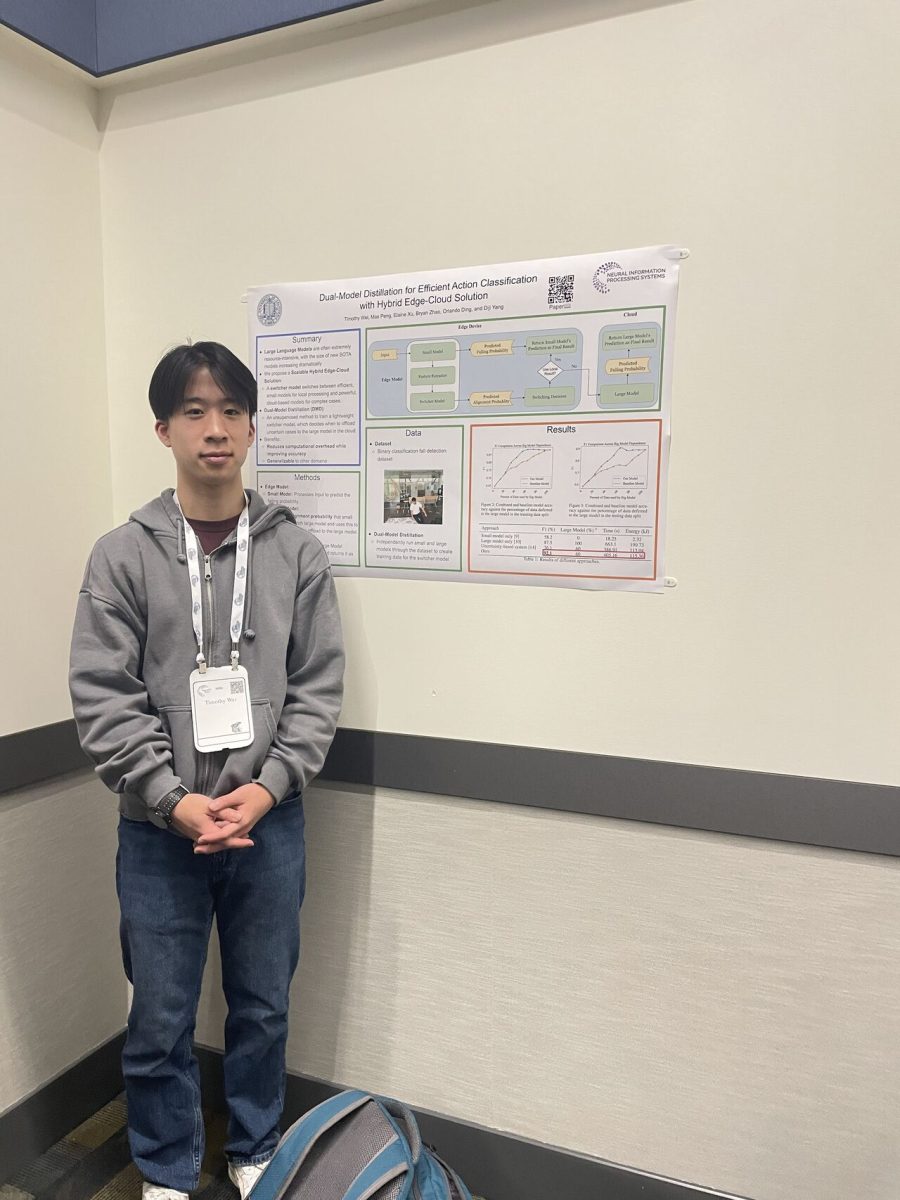

Fan skis at Palisades Tahoe with the Olympic Valley Freestyle and Freeride Team (OVFree). Freestyle mogul skiing, which he competes in at resorts across the country, involves taking sharp, precise turns through a mogul course and performing two jumps, one at the top of the course and one at the bottom — while being awarded points for turn technique, jump execution and speed.

While moguls — large man-made bumps in the snow — pose a technical obstacle, the bulk of the challenge in Fan’s event are the 20-foot high jumps, where he launches himself off a ramp at high speeds and performs complex aerial tricks like the back-double-full, a backflip combined with two 360-degree full-body twists.

With four years of experience on a team, Fan is no stranger to injuries on the mountain — he recalls landing on his head, spraining his hip and spraining his medial collateral ligament (MCL). He’s also seen teammates and other competitors end up with more severe injuries, including anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or MCL tears in their knees.

“A lot of the time I’m pretty scared, and that messes with the way that I set the trick,” Fan said. “You have to really learn to set it [prepare your body and positioning] without being worried about dying, because if you’re worried, you’ll end up either oversetting the trick or setting it wrong, which are both even more dangerous.”

In order to execute these tricks, Fan starts by practicing on a trampoline to learn the precise body movements needed to be efficient and consistent. Once he’s comfortable with the motions, he puts the trick in context at ramp facilities, which implement a variety of safeguards — like roller skis, foam pits and water landings — allowing him to practice the actual tricks while wearing skis without fear of injury.

Currently, Fan is perfecting his corkscrew 720, an off-axis spin twice in the air. “I’m not fully comfortable with it, and it’s pretty scary, so I’m gonna be training it onto the water a bunch and a bunch more until I can say: ‘I got this for sure,’” he said.

Like Fan, junior Thalea Charton also competes in freeride skiing; Charton competes with the Kirkwood Freeride Foundation, and her competitions take her across entire mountains, not just bounded courses. Freeriding involves charting “lines,” or paths through the natural terrain, and executing them fluidly with steep turns and cliff jumps as high as 20 feet.

The unpredictable and widely varying conditions for freeriders creates unique risks for competitors — Charton recalls having once overshot a trick, landing on a rock and somersaulting through the snow.

While it’s impossible to replicate the exact conditions of each run, Charton and her team consistently practice around their home mountain, Kirkwood. Minimizing risk involves careful planning, mapping out trajectories and identifying runouts, areas to slow down and gain control. To protect their bodies, freeriders wear back and body protection and squat heavy weights to be able to stick stable landings.

The dangers gymnasts face

Outdoor extreme sports like extreme skiing have a reputation for risk, but indoor sports like gymnastics also carry significant dangers. Gymnast Esha Verma has learned to be comfortable with the dangers posed by events like the balance beam and high bar. Any imprecision in movements can mean falling and suffering a concussion, or worse.

Having participated in gymnastics competitions since she was six years old, Verma’s seen her fair share of hard impacts, acquiring injuries ranging from her foot’s arch collapsing to spraining her back.

When practicing skills to prepare for the beam, Verma, a junior, starts by training on the floor without the elevated beam, so that she doesn’t fall as hard when she makes a mistake.

“If your body can do the skill without you thinking about it, that’s when it becomes safe,” she said.

At the same time, she adds small heights bit by bit through mats or other cushions, working her way up incrementally to build comfort until finally reaching the four-foot height of the beam.

In addition, Verma and her team spend 30-45 minutes of every practice focusing solely on strength training to ensure their bodies can handle hard landings from high up in the air.

Although Verma isn’t competing regularly this year as her academics take precedence, she still goes to practice and finds that, ironically, practicing allows her to relieve some of the stress of school.

“Sure, it’s scary when you’re going for something, but if you’ve been training for enough years, your body knows how to do it,” Verma said. “Once you get over the fear and go for it, it brings your mood up like nothing else.”