In the stands during the Oct. 24 home water polo game, students from the school started name-calling and chanting against Cupertino High as tensions in the game rose. College and Career counselor Sierra Ward stepped in to stop the crowd as profanity joined in the mix. The school received complaints about the incident, and students were told to write apology letters to the Cupertino players for their actions.

Following the enthusiasm of the crowd, it’s easy for cheering to diverge into jests at the opposing team, aggressive “boo”s or condescending chants. However, coaches like athletic director Rick Ellis strongly believe that, especially at the high school level, cheering should only be positive.

“I believe that our fans should only be cheering for our teams and things that our team does, not against the other team,” Ellis said. “I think once we start cheering for mistakes that the other team makes, or we start focusing on the other team’s players, it’s a slippery slope.”

Trash-talking can be especially harmful when directed at a singular student athlete, whether it’s one from the school who made a mistake or an opponent who did well. Ellis explains that not only is it damaging to the morale of the student, it also reflects badly on the people in the stands.

Referees have also historically been victims of harsh comments from fans when they make calls that favor the opposing team. Parents, in particular, can be very vocal in protesting referees’ calls. When parents get too aggressive, Ellis explains that sometimes administrators need to step in and stop them because it sets a bad example for the students.

Respectful cheering helps build sportsmanship in the athletic community, fostering a safer environment where all players, both on the school and opposing teams, can feel supported. As the winter season sports ramp up, it’s increasingly important for fans to be mindful of their actions from the stands.

“I take pride in receiving a comment from another administrator from another school about how respectful our students were in the stands,” he said. “I think that’s a good compliment. I like to be able to [win big on games] and hear that as well.”

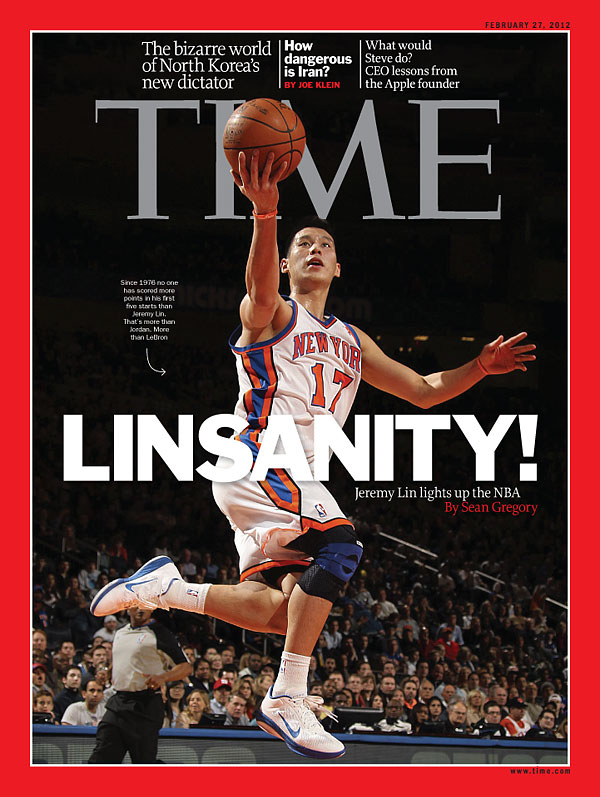

At the college and professional level, trash-talking the opposing team is significantly more common. During the Nov. 9 Ohio State University and Purdue University football game, the crowd went wild with laughter as Ohio State’s marching band formed the shape of a bear excreting an emoji poop onto the logo of University of Michigan — the rival they faced on Nov. 23. Ellis is worried that students who watch these games on TV or Instagram will see the trash-talking and replicate it at high school games.

The CCS guidelines, which is signed by all high school athletes before the start of the season, contains a section outlining the guidelines for sportsmanship. According to the guidelines, athletes can be ejected for, among other reasons, “unsportsmanlike conduct” if they use profanity, disrespectfully address an official or taunt, bait or spit at anyone. Although fans are not bound by contract to the same terms, administrators believe that they should still follow these guidelines.

At the school, incidents where students are caught trash-talking aren’t frequent, they do occasionally happen. To try to keep everything respectful, the school usually has an administrator on site, especially for sports like volleyball, basketball and football where fans are particularly close to the court and players. However, it is ultimately up to the spectators of the game to act respectfully.

“It’s hard to know how much [jesting] should be allowed. So to be safe and classy, we should only be cheering for our students,” Ellis said.