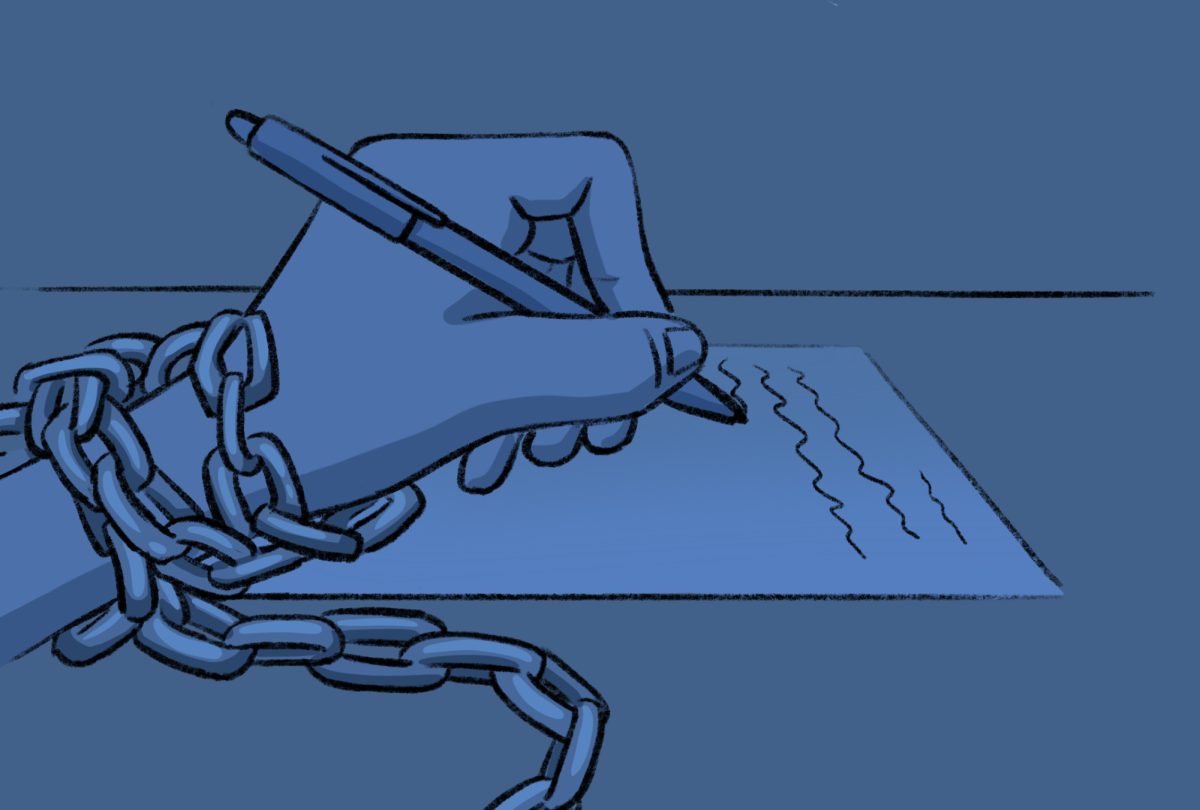

From late April to May 2024, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker recorded over 12 instances of violent assault that targeted journalists reporting on protests surrounding the Israel-Gaza war at UCLA alone. For nearly as long as journalism has existed in the country, there have been obstacles for reporters who strive to publish truthful information. Student journalists, who are often made aware of standard journalism practices and ethics, should be explicitly informed about their freedoms and rights.

Perhaps the most infamous court case limiting student press is the 1988 Supreme Court Case Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier. The principal of Hazelwood East High School demanded the publication (represented by student editor Cathy Kuhlmeier) to withhold select articles regarding subjects like teen pregnancy from an issue. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that school administrators reserved the right to exercise editorial control over content “inconsistent with the shared values of a civilized social order,” permitting the district to maintain control over what the student publication released.

Looking at the current bench, in which conservatives hold a 6-3 majority, there’s also a rising sentiment of general mistrust in media outlets. This may lead to further restrictions on the press freedoms of many publications.

Fortunately, California is one of a handful of states that has historically offered the most extensive protection to student journalists. Section 48907 of the California Education Code (EDC), enacted in 1976, was the first to establish rights for school publications and notably the only one of its kind to precede the Hazelwood decision.

Since then, these laws have defended freedoms of student press, but not without continuous challenges by administrations attempting to push back on unfavorable media portrayals. This is exactly why it is crucial for student journalists to be aware of their rights — these issues remain highly relevant today.

Just last spring in 2023, members on the staff of the Oracle, Mountain View High School’s publication, brought a lawsuit against their principal over threats she directed against the school’s newspaper. Former adviser Carla Gomez, editor-in-chief Hannah Olson and reporter Hayes Duenow accused principal Dr. Kip Glazer of overreaching the limits of her power and retaliating against the release of an article.

Duenow and three other students were writing in-depth article that addressed instances of sexual harassment experienced by students, using pseudonyms for the names of the perpetrators. In a series of confrontations while the story was being edited, the students were approached by Glazer, who allegedly “bullied and intimidated the student journalists” according to a letter by their lawyer.

The article was ultimately published but not without several significant edits being made — details about a specific disturbing incident, the harasser’s involvement in a school program and criticism expressing concerns against the administration’s potential inaction were all excluded from the final version of the story.

Less than a month later, students attending Mountain View High School were notified that the Introduction to Journalism course, formerly a prerequisite for joining the Oracle, was set to be combined with the yearbook course Publication Design 1. In other words, formal training specifically for newspaper writing would be removed from the pathway. To make matters worse, the administration terminated Gomez’s position as the adviser, replacing her with drama teacher Pancho Morris.

Circling back to EDC 48907, California law generally shields articles about sensitive topics from censorship. Students should be thoroughly informed of the potential consequences and reactions of their work, but California’s student press laws ultimately limit — not order — these to suggestions to censor parts of their story. The only exceptions are if parts fall under the category of unprotected speech, referring to “obscene, libelous or slanderous” expression or disruptive content that may incite peers to engage in dangerous or illegal actions. But as long as such unprotected speech is not reflected in their work, the message is clear: Student journalists retain every right to be bold and investigative in their reporting.

Also included in EDC 48907 are protections defending advisers from retaliatory actions. This section was added in an amendment through the Journalism Teacher Protection Act, passed in January 2009, which intended to protect advisers and reassure students that they can proceed with honest reporting without putting their advisers at risk. The amendment defends teachers from being “dismissed, suspended, disciplined, reassigned, transferred or otherwise retaliated against solely for acting to protect a pupil.”

In instances such as the 2022 case involving adviser Adriana Chavira from Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Los Angeles, where Chavira won her case in an appeal hearing, the adviser’s suspension was rescinded and Chavira was protected against further retaliatory actions. Disappointingly, Gomez wasn’t as fortunate and was barred from returning to her post. As of Jan. 22, the case is still ongoing.

The Oracle’s case underscores how even in California high school journalism must fight for freedoms to operate like a professional publication, including the rights to express their desired opinions or perspectives. The elimination of the journalism pathway entry class and the replacement of the publication’s adviser has placed the Oracle in an unstable position, and this situation cautions that the battle continues for publications to have true independence from school administrators.

Due to decreasing enrollment that began during the pandemic, SHS also combined Journalism 1 with the Yearbook course starting in ‘21-’22. This could have likely discouraged many students from joining the journalism pathway, especially for those who had been interested in writing specifically for the newspaper rather than the yearbook.

Furthermore, adviser and English teacher Michael Tyler raised the possibility of a conflict of interest with students themselves: In some investigative stories, they could be criticizing the very administrators who are or may write their letters of recommendation for college. This could be even more discouraging for student journalists, who would want to leave good impressions on their teachers and school staff.

“The challenge is to cover an institution that you are also a part of. Student journalists come under direct pressure from administrators, teachers, parents and community members to avoid publishing or to not cover a certain topic,” Tyler said. “It requires a real commitment by student journalists and their advisor to maintain that independence and skepticism.”

In The Falcon’s policies, prior review from any school officials except the adviser is prohibited. Corrections for accuracy are welcome, but changes to the content of a published story will only happen if the content falls under the “unprotected speech” category, and the Falcon reserves the right to decline requests to take down stories published on its website.

The constant pushback from school administrators seeking to use student media as a means to protect their own reputation must be met with resistance. Drawing from the First Amendment, truthful reporting is foundational to building a democracy founded in trust. Looking ahead, it’s incredibly important for students to recognize their essential roles and rights as journalists in order to uphold the standards of truth — the fight to continue upholding student press freedoms is far from over.

Editor’s Note: For a guide to California’s Student Press Freedom Laws, visit splc.org/know-your-rights-california/.