On Sept. 30, Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law Assembly Bill 1780 (AB 1780), titled “Independent institutions of higher education: legacy and donor preference in admissions: prohibition.”

The bill, effective starting Sept. 1, 2025, puts an end to legacy and donor admissions — the practice of giving children or grandchildren of alumni or donors an advantage during the admissions process — for all private colleges and universities in California.

Proposed by Assemblymember Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) in January, AB 1780 closely resembles another bill (AB 697) proposed by Ting in 2019. However, the earlier proposal failed due to concerns from private colleges about its impact on financial aid for low-income students.

In a statement on the day the bill was signed, Newsom said the goal of the bill is to open higher education to everyone and offer admission solely on the basis of merit, skill and hard work.

While private schools have practiced legacy and donor admissions since the early 20th century, California public school systems — the UCs and CSUs — stopped giving preferential treatment to children of alumni or donors in 1998, two years after California’s Proposition 209 prohibited the consideration of race and gender in public institution admissions.

The passing of AB 1780 makes California the second state, after Maryland in April, to ban legacy admissions for both private and public universities. Other states like Colorado, Illinois and Virginia have similar bans that apply only to public institutions.

The road to AB 1780: Lawmakers and admissions officers reassess traditional admissions processes

Ever since the 2023 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard declared race-based affirmative action — the practice of using race as a factor in admissions — unconstitutional, the debate surrounding the various forms of preferential admissions has taken a nation-wide spotlight.

In a 6-3 Conservative-led decision, the court noted that college admissions are zero-sum, or a situation in which total gains and losses sum to zero: a benefit to one applicant directly disadvantages other applicants. Deciding that race-based admissions would unfairly disadvantage applicants of different races, the majority found that affirmative action violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Critics of legacy and donor admissions argue giving wealthy or connected applicants preferential treatment unfairly harms other applicants.

Recent National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data from the 2022-23 school year shows that 32% of selective 4-year institutions consider legacy status during admissions. It’s worth noting, however, that this statistic varies greatly between studies — the number ranges between 32-60% depending on how loosely a study considers legacy preferences, since the extent of preferential treatment depends on the school.

Several high-profile cases in the past where seemingly unqualified students with wealthy parents got into top colleges have brought attention to the practice. New Jersey real estate developer Charles Kushner was found to have donated $2.5 million to Harvard in 1998, soon before his son, Jared Kushner, was admitted. (Jared Kushner, also a real estate developer, is now the husband of Donald Trump’s daughter, Ivanka.) His high school teachers said they were disappointed that he was admitted over other students who they felt had the merit to get in, stating that Kushner’s GPA and SAT scores did not warrant admission.

Former president George W. Bush is another example of how legacy admissions serve as a form of affirmative action for the rich and influential. Bush, who had strong legacy ties to Yale University through his father and grandfather, was accepted to Yale in 1964 despite having a mediocre 1,206 SAT score and indistinguishable extracurriculars. His grandfather, Prescott Bush, was a prominent U.S. Senator, and his father — who would become president in 1989 — was a successful businessman and politician at the time.

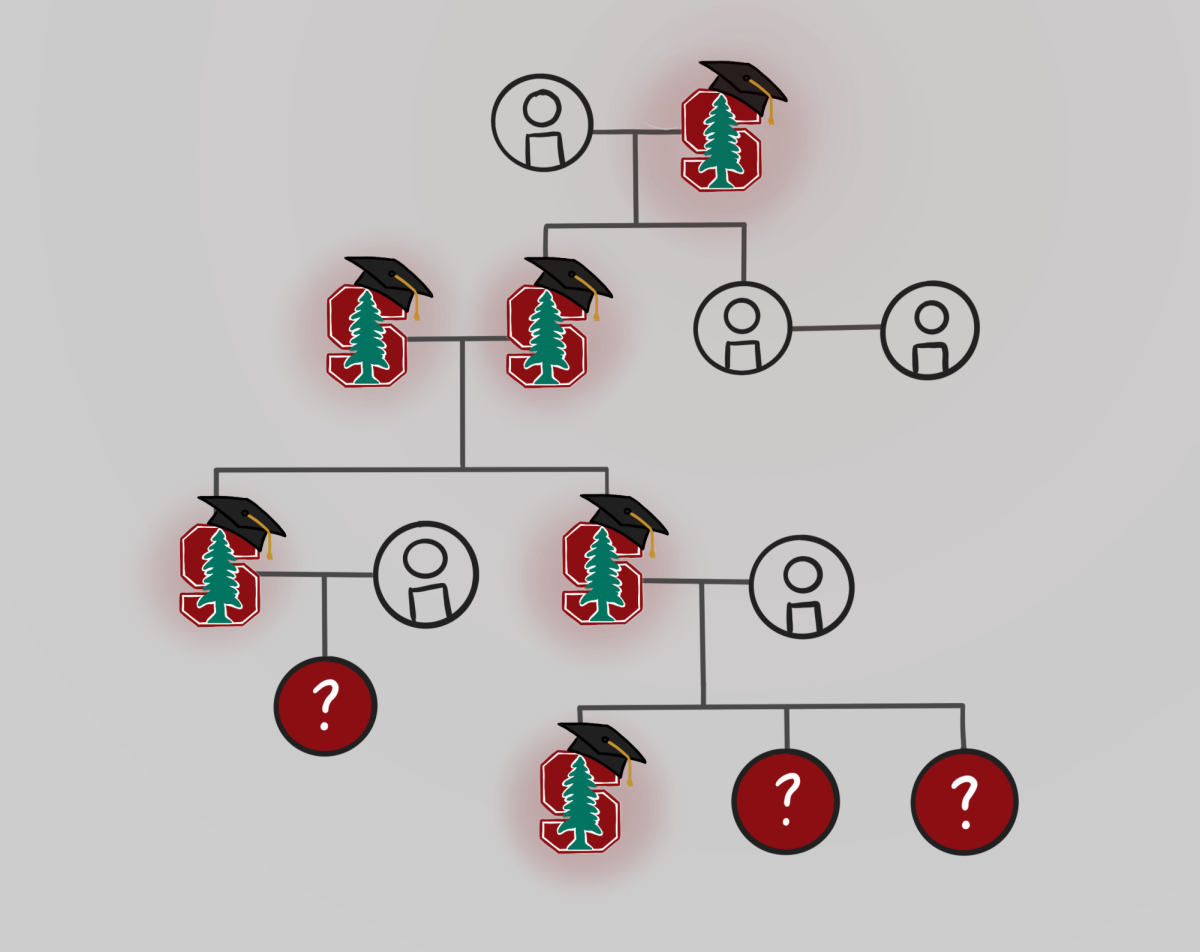

At many highly prestigious colleges like Stanford University, Harvard University and Yale, legacy admissions have been a longstanding tradition ever since the early 1900s. College admissions data show that 32% of the Class of ‘27 at Harvard are legacy students and 14.9% of the Class of ‘26 at Stanford are likewise. These colleges claim legacy and donor admission foster alumni relationships, encourage donations necessary for financial aid and help build a stronger campus community. By contrast, other colleges like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have never considered legacies in their admissions process.

Still, having legacy status doesn’t guarantee admission into the school. Students with legacy or donor families are also not informed on how heavily their status was weighed in the admissions decision. According to a study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard research group, legacy students are, on average, more qualified for elite schools than the typical applicant, as they often come from well-educated families with resources to bolster their child’s application profile. In fact, the study found that if a student’s legacy status was ignored, extracurriculars and athletic recruitment would still make them 33% more likely to be admitted than another student with the same test scores and demographics.

But once these students are given preferential treatment as legacies or children of donors, the admission gap between legacy students and non-legacies grows substantially larger. Analyzing data from the “Ivy-Plus” schools — the eight Ivy League schools, along with Stanford, MIT, Duke University and University of Chicago — the Opportunity Insights study found that admission rates for legacy children with families in the top 1% financially were five times the average. Rates for legacy children with families below the top 5% were also over three times the admission rate of a typical applicant.

Race has also played a part in the legacy admissions discussion. Just days after the Supreme Court’s decision on race-based affirmative action, the Lawyers for Civil Rights filed a lawsuit on behalf of African and Latino advocacy groups against Harvard, challenging its use of preferential treatment for legacy and donor applicants. The complaint outlines that since 70% of Harvard’s donor-related and legacy applicants are white, the practice furthers discriminatory practices against minority groups.

Incidentally, colleges and states have been reevaluating traditional admission processes with an eye toward encouraging more merit-based admission.

Arguments for legacy admissions

From the perspective of college admissions officers, accepting legacy and donor admissions comes with a number of benefits. Legacy admissions help foster stronger relationships with alumni who wish for their child to attend the school as well, making them more likely to donate to their alma mater.

An arm up in admissions also encourages wealthy families without alumni connections to make significant financial contributions to a college, either through large donations or by funding projects around the campus. The donations made to colleges are in part used for financial aid to assist those who are unable to pay full tuition.

In a Harvard Committee’s 2018 report on race-neutral alternatives, the committee expressed that Harvard alumni donations help secure Harvard’s position as a higher learning institution because it helps make financial aid policies possible, diversifying the student body.

However, other colleges such as Pomona College, a high-ranking private liberal arts college in California, reported no noticeable difference in donations before and after they banned legacy and donor admissions in 2017.

Guidance counselor Brian Safine argued that although several of his former students have benefited from legacy admissions, the financial rationale is an insufficient reason to support the practice.

“If Stanford was profiting from selling overpriced prescription medication to the sick and poor, and that money went back to provide scholarships to be underrepresented, would that be OK?” Safine said. “Anyone can say, ‘Oh, the money that we raised from this goes back to help others,’ but in the end it’s a big moral question of whether the ends justify the means.”

Advocates for the practice argue that aside from possible economic benefits, accepting more legacy students helps colleges maintain a more consistent yield rate — the percentage of admitted students who actually enroll in a particular college or university. A higher yield rate is an indicator of their desirability among prospective students and can improve a college’s ranking in publications like the “U.S. News Best Colleges.”

College and Career Center adviser Sierra Ward worked as an admissions officer for seven years at Bucknell University before entering the college counselor industry 18 years ago. In her time at Bucknell, she witnessed some of the advantages colleges obtain through legacy admissions.

“Legacies typically have a high yield just because there’s more enthusiasm to attend the school,” Ward said. “They might apply [early decision], which is binding, so removing [preferential treatment for legacies] might take away part of your applicant pool because they might have to go elsewhere.”

Schools also argue that legacy admissions help directly foster a sense of community and tradition within their campuses. SHS seniors Max Dubin and Fletcher Dubin have legacy connections to Harvard through their father, grandfather, great uncle and cousin. As a result, they say they feel more focused on the college than a typical applicant. Max notes that admissions officers are more likely to fully read his essays because of his legacy status.

Fletcher remembers going to several alumni reunions with his father, where he got to meet other graduates and learn more about the school.

“I don’t really think [having legacy] benefits me that much, but it changes how I feel about Harvard — it’s like I’m more interested,” Fletcher said. “I have more general information about the school, and hear a lot about my dad’s experience there.”

Bucknell University, located in Lewisburg, Penn., also considers legacies in its admissions decisions. While Ward said she is glad underrepresented students will now have a fairer chance at admissions, she has also seen the underlying sentimental connections that legacy families sometimes share with the institution.

“Say there’s a student who’s been coming to our football games since they were three years old, decked out in orange and blue and wearing all the swag,” Ward said. “That’s what you want to build — the loyalty for multiple generations of families, and so they keep coming back. Sometimes that increases your donations, and school spirit goes up, and that’s a great thing.”

The path towards a meritocracy

In Saratoga High, several students with legacy connections to Stanford or the University of Southern California may be negatively impacted by this policy change, but Silicon Valley’s uniquely high percentage of immigrant parents: 37.4% of Silicon Valley is foreign-born, compared to 13.3% nationally.

Ward notes that a significant portion of the SHS student population has at least one parent who attended college abroad, and would likely see a positive impact from the legacy ban.

While the ban on legacy and donor admissions may not have a large impact on most SHS students, it demonstrates the recent, nationwide trend toward purely merit-based admissions. On Nov. 7, U.S. Senators Todd Young (R-IN) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) proposed the “Merit-Based Educational Reforms and Institutional Transparency Act” (MERIT Act) to continue the fight against preferential treatment for legacy and donor students nationally.

But is it possible to ever truly level the playing field and reward only a student’s merit?

According to Safine, separating one’s birth from one’s merit is impossible because education opportunities vary greatly across socioeconomic tiers. For instance, California high schools vary significantly in academic rigor depending on the area, and even standardized testing is influenced by a student’s home environment, including the educational level of their parents.

“We are very fortunate in Saratoga to have motivated students, motivated parents, motivated staff members, access to tutors and access to private college counselors,” Safine said. “Those resources don’t exist in every other community. So, as hard-working and dedicated as our students are, they still benefit from certain advantages by living in this community as students head towards college admission.”

Most colleges try to account for these disparities by viewing students holistically, or by looking at their achievements in the context of challenges they faced, to help identify students who have excelled despite socioeconomic disadvantages.

Ultimately, the banning of race-based affirmative action and now legacy and donor admissions in California removes factors clearly out of applicants’ control. In the following years, colleges and policy makers nationally will likely continue to reassess traditional practices to provide fair opportunities for all students, regardless of their background.

“I would say this is a very tumultuous time for the world of college admission,” Ward said. “In the last year and a half, colleges have undergone a lot of changes with legacy admissions, the Supreme Court decisions, AI integrity and standardized testing. Legacy admissions is an option that is not available to everyone, and that inherently is inequity, which is something that a lot of us [counselors] are opposed to because that’s not fair.