On Jan. 6, 2021, in an attempt to undermine the 2020 election results, rioters supporting then-President Donald Trump stormed into the Capitol building. Though, on that day, Trump encouraged the crowd to march to the Capitol “to peacefully and patriotically make [their] voices heard,” in the prior weeks, he had repeated claims of a falsified election and encouraged the crowd to “fight much harder,” fueling mistrust in the fairness of the election. Over the course of U.S. history, in only four prior elections have high-ranking officials contested the legitimacy of an election; never before had protesters broken into the Capitol due to such claims.

Trump was subsequently impeached by the House of Representatives on Jan. 13, 2021, on the charge of incitement of insurrection. Of the one hundred senators participating in the subsequent Senate vote, 57 voted guilty while 43 voted not guilty. Though a two-thirds majority for a guilty verdict was not reached, the string of events remains an exemplar of a split Capitol Hill and a divided nation.

Polarization in the U.S. is worsening amid changing media patterns, gerrymandering and social identification. Since the 1950s, the difference in mean positions (scores assigned to representatives’ ideological placement, where -1 is the most conservative Republican and +1 is the most liberal Democrat) in the Senate and House has risen by about .5. The average ideological view measured between the two parties’ representatives has also doubled between 1972 and 2004.

Adding to the trend, the number of moderates in Congress has declined since the 1980s, falling to around two dozen in 2022, according to the Pew Research Center. Just half a century ago, political moderates — indicators of bipartisan collaboration — encompassed 30% of Capitol Hill.

However, within Congress today, the “middle ground” where liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats can compromise has become near nonexistent; according to the Pew Research Center, the last time conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans largely overlapped ideologically was in 2004, marked by the departures of Republican Rep. Constance Morella and Rep. Benjamin Gilman who lost re-election and retired, respectively.

Despite reputation as a solid-blue state, local policy discrepancies nevertheless polarize Saratogans

California votes overwhelmingly Democratic, but there are factions within the party. Senior Anushka Tadikonda, who works as part of the Democratic National Convention digital team and interns for Campbell resident Evan Low’s congressional campaign, noted that issues such as drugs and poverty beget subtle divides among Californians.

“When we have a rise in homelessness or drugs like fentanyl, sometimes we allow our liberal mentality to maybe not put all of our focus and money and time into that, even though we preach it,” Tadikonda said. “Instead we look at identity politics, which is very important, but gender-neutral toy aisles [aren’t] necessarily the biggest issue on the table.”

Tadikonda said Saratoga is contained within a more moderate voter district: California’s 16th congressional district, which encompasses the South Bay, Mid-Peninsula and coastal San Mateo County. The district favors more moderate candidate Liccardo over more liberal candidate Evan Low because Liccardo appeals to residents who work in the tech industry. Tadikonda said Low’s “California mentality on an assembly level” parallels the passage of policies such as gender-neutral toy aisles.

She added that voting patterns depend on the local region, and, in the case of the Bay Area’s 16th district, tech policies are more important than the overall Democratic agenda. These political patterns translate to policies favoring tech companies and startups, reflecting the entrepreneurial nature of the area.

Social media’s “echo chamber” fuels radical ideologies

Social media has become a battleground for politics. Whether regarding candidates or voters, fiery claims and rants have flooded the feeds of many users, leading to further polarization amongst voters.

Trump typically posts controversial “Truths” — messages modeled after those on social media platform X — on his app Truth Social. Such Truths include targeted rhetoric toward Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris, referring to her as “Comrade Kamala.” Trump has also posted fake AI-generated images of celebrities, such as Taylor Swift who recently threw her support behind Harris, endorsing himself.

A 2016 Harvard study found that politicians with extreme ideologies, such as Trump, attracted larger audiences than moderate peers on social media. The algorithm pushes messages reflecting more extreme viewpoints, which are more likely to be circulated among users.

Researchers call this phenomenon the “echo chamber” effect, where people in a digital environment are exclusively exposed to opinions, information and perspectives that reinforce and amplify their beliefs.

False news spreads faster than true news in all categories of information, especially regarding political news, according to the Science Journal. Additionally, every word in a Tweet (a message on X) that targeted the opposing political group increased the likelihood of that post being recommended by 67%.

One explanation for why misinformation spreads so fast lies in the theory of confirmation bias, which states that people tend to believe articles that support their preexisting beliefs. In this environment, individuals interact mainly with those with similar viewpoints, narrowing perspectives and fueling more extreme political views.

Social media algorithms, in turn, have control of each political party to extremists at each end of the spectrum, turning platforms into a battleground between the 7-8% of radicals on either side of the American population for the country to see.

Media bias and the rise of opinionated partisan media

Partisan news outlets, including Fox News and MSNBC, have also exacerbated polarization by presenting opinions about news rather than facts left to the viewer’s interpretation.

With entertainment and news growing increasingly entwined, this paves the way for more extreme reporting and non-factual reports — by blurring the line between misinformation, opinion and reporting, these media outlets enjoy skyrocketing ratings and profits.

This wasn’t always the case — the 1949 Fairness Doctrine required broadcasters to present controversial issues with a fair reflection of multiple viewpoints. However, this was abolished in 1987 after the Federal Communications Commission alleged in a report that the policy violated free speech and hurt public opinion. The abolition was followed by a lifting of editorial and personal-attack provisions in 2000 and language rules in 2011, opening up the arena for politically extreme hosts.

For example, in the months leading up to the 2020 election, one of the most popular former hosts of Fox News — Tucker Carlson — spun millions of viewers through accusations that the Democratic Party despised the country, or that electronic voting company Dominion was involved in a plot to steal the 2020 election.

A study by the Pew Research Center indicates that just 35% of Americans can identify all sampled pieces of opinionated information, while only 26% identify all pieces of factual information from a study providing five sampled pieces of information from the real world. Such a decline in accuracy indicates that when a claim matches people’s pre-existing notions, they’re more likely to accept it — furthering polarization.

Gerrymandering’s effect on Capitol Hill

Within the US, the two major parties — the Republican and Democratic parties — tend to produce extremely polarized candidates such as Tom Cotton, a Republican Senator from Arkansas. This is in part due to the gerrymandering of districts in America.

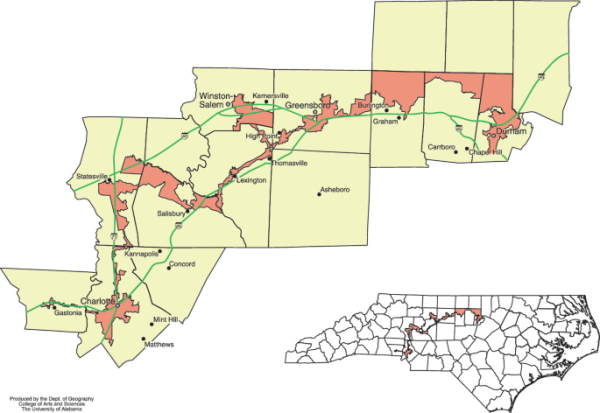

This can be attributed to processes like gerrymandering, where district lines are drawn to favor a select party. Gerrymandering by state legislature forms districts that heavily favor one party, creating “safe districts”. Currently, with advanced computing technology, political agents can utilize this innovation to aid their party strategically.

Since these “safe districts” draw members from one specific party, this reduces the incentive for candidates to appeal to moderate voters. Consequently, candidates adopt more extreme positions to win over their party’s base, enhancing polarization.

Another way these primaries tend to polarize candidates is by having closed or partially closed primaries. Closed primaries ensure only members from that party can select the candidates, whereas in open primaries, regardless of party affiliation, voters can select a primary to vote in. This occurs in 16 states, including New York and Florida, resulting in independent voters not receiving a chance to participate in the primary.

Potential solutions lay in social media reform, fact-checking and discourse

Amid a fiery political battleground, solutions to dampen ever-growing polarization arise. One possible route is social media reform.

In 2021, the Wall Street Journal published a series of investigative articles called the “Facebook Files,” where researchers identified harmful side effects of the social media platform, resulting from rejected reforms. Past changes have worsened the divide on the platform.

Instead of allowing the social media industry to self-regulate, which Facebook’s case has proved to be an extremely difficult task, there are other solutions. With more external regulations, such as the repeal of Section 230 — a policy granting immunity to social media companies over posts and information on their websites — the government and the public can have a greater degree of control over these companies.

The Brookings Institution suggests that external regulators could implement algorithmic adjustments and refine systems in the social media industry to protect rightful political speech and remove disinformation.

In the meantime, instead of blindly trusting all media from online platforms, consumers can fact-check sources to prevent media bias and democratic backsliding. UC Berkeley provides a set of fact-checkers that cover political speech, online urban legends and more.

Outside the digital realm, Tadikonda emphasizes discourse as a crucial method of de-polarization. Rather than dismissing opposing viewpoints, she believes that people should be open and understanding. Many nonprofits have started to host workshops for meaningful conversation, including Princeton’s Bridging Divides Institute and Braver Angels. A takeaway from these workshops was to clarify stereotypes each group held to reduce tension.

“At the end of the day, logically, you end up with common ground. Everyone just wants what’s best for their country and what they [envision] as a beautiful country for their kids and their family and themselves,” Tadikonda said. “If we don’t have that discourse, we’re never going to understand what someone else is facing and what they need.”

Social identification within political parties: AKA affective polarization

The creation of these parties means social interactions between party members. As a social species, humans find group identity and affiliation to be essential, as they have evolved in a world where the simplicity of survival requires collaboration and cooperation.

As a part of one of these political parties, people psychologically separate the world into two groups: those who are in the party and those who are not. This rift triggers positive feelings for those in the party, the “in-group” and negative feelings for anyone else, the “out-group”, perpetuating the ideological gap between the two groups. This phenomenon is known as affective polarization.

In many surveys, affective polarization, which is calculated by subtracting the out-group feeling from the in-group feeling, has been increasing among the American population. The average feeling — from feeling thermometers — toward the outgroup has dropped from 48º in the 1970s to 20º in 2020 on a 0-100º scale, with 0º being very cold and 100º being very warm toward the person.

Another proposed explanation of affective polarization involves economic crises, including the Great Depression and the 2008 Financial Crisis. Voters become more ideologically extreme sometimes during crises due to economic promises or scapegoating. More extreme groups that attack out-groups tend to blossom during these troubling economic times, thus leading to additional affective polarization.

Stereotypes of the opposite party also increase affective polarization in the stereotypes. One University of Chicago study finds that Americans create stereotypes about certain voting parties. The study shows that Americans believe that 32% of Democrats identify as LGBTQ; however, only 6% of Democrats actually fit into this category. In addition, Americans think 38% of Republicans as earning over $250,000 per year, whereas it truly lies around 2%. Likewise, Tadikonda emphasized that when people see a policy point, they normally tie it to a party instead of a candidate.

“When you think of a policy point, you are connected to a party,” she said. “There are specific policy points that you think of when you think of a party, and that shouldn’t be the case. And so that just leads to more polarization.”

Though affective polarization doesn’t directly cause political violence or democratic backsliding, these emotions from affective polarization interact with voting systems, candidates and personal relationships when combined with media. The result is the unprecedented stew of opposing forces and deep distrust that now characterize American politics.