Picture this: You’re doing research for your school project on Federalism, and you begin to consult different news sites for information. Immediately, you’re blinded by the passive-aggressive request to “Accept Cookies,” which you must bypass in order to stock up on federalist gold. The tiny font you can barely read includes information about liabilities and user data, but in a rush to finish your report by 11:59 p.m., you hastily click away whatever will remove the popup, not realizing you’ve taken a step toward sacrificing your personal data for less than it’s worth.

Data collection on social media and websites is typically used to train recommendation algorithms and, more recently, for growing the libraries that AI accesses. More often than not, this data collection goes overboard when companies collect so much data that it becomes a breach of privacy. If users aren’t careful, they won’t know what they’re consenting to.

Cookies’ role in data collection

Most people have seen the “Accept all cookies” message that appears when visiting a new website. Cookies sound innocent enough, but experts caution that they actually store pieces of information, including names, accounts, location data and search history. These pieces of data help the website remember you when you return. Similarly, the “Do not sell my personal data” and “I agree to the Privacy Policy” messages send a more incriminating and obvious warning.

It’s not just websites that collect information from browsers — social media apps like Facebook and Instagram share 57% and 79% of your data, respectively, with third parties like advertisers. They not only track your interactions with posts and likes, but also your personal information, device information and location.

For example, by simply making an account, Instagram has access to all your user data that can be sold to third-party marketers. The company’s data policy describes five different categories of information they have access to: content provided by the user, connections to other apps, general device usage, financial transactions and information others provide about the user. In fact, under the “Content You Provide” category, Instagram even has access to data from the user’s camera, which is used to “suggest masks and filters that you might like, or give you tips on using camera formats.”

Conversely, if a user were to decline the request for cookies, they would have a more basic search experience without personalization based on previous searches or personal data. In the grand scheme of things, personalized searching isn’t as much of a preference as protected privacy, which is what declining guarantees.

In certain cases, the U.S. has regulations which specifically protect privacy. For example, The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), enacted in 1998, forces companies to obtain parental consent to use the data of children under age 13 using their site. This requirement, though easily bypassable, adds an extra step to data collection that enables users to pay closer attention to what data is being collected.

Incorporation of AI and the flight of artists

This information has become increasingly important, given that Meta’s AI has been incorporated into Instagram’s main search system. The algorithm has been working to train their AI with user data and public posts. This has been active in both the U.S. and U.K., with only the U.K. receiving notification of changes, and users have been desperately searching for ways to opt out of the system — a checkbox that can only be found deep in a user’s settings. To the dismay of consumer advocates, the U.S.’ privacy policy is more lenient than the U.K.’s, where the entire Meta policy has been at a halt for the last couple of months. Users, for now, can send an independent request to Meta to delete their information, a process that has no fixed response timeline and no guarantee of success.

These are justified fears, given that AI art has recently been a new trend in the content creating space. Because of this new policy, artists have been moving their work off Instagram and on to a new app called Cara, in fear that AI will copy their work without compensation. The new platform has seen ample growth, even causing the page to crash a couple of times. There are already tensions between artists and AI due to uncredited usage of work, but this deeper AI access to millions of pieces of work has the potential to bankrupt artists.

User data being sold for advertising

Another aspect of user data collection is advertising. In one recent case, United States v. Google LLC, Google was charged with monopolizing data collection through advertisement technologies. In the past few years, Google has eliminated ad marketing competitors by acquiring smaller departments and companies. This behavior is pushing the company toward being a monopoly in the data collection industry, which is illegal under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act.

This case demonstrates an illegal increase in the barriers to enter the search engine and data collection industry. Because Google is able to collect so much data, it is able to improve its search engine at a rapid pace, faster than competitors that don’t have access to such a trove of data. Critics say monopolization of the data collection and ad marketing industry are problematic because granting Google complete control over the market would incentivize corner-cutting and unsafe management of user data, invading the privacy of users.

In another case in February 2022, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton sued Meta for collection and publication of biometric data. Specifically, Meta is alleged to have knowingly stored a data bank full of images compiled of users on the app, which it had been using for ad targeting. The ad targeting technology specifically uses data about items and filters being used by users to target with specific ads. Paxton ended up winning the lawsuit, securing $1.4 billion to be paid over the course of five years.

These face-offs with large corporations are becoming increasingly common. Take the case of a Florida man who sued Disney for his wife’s death. This was due to an allergic reaction from food served at a restaurant in Disney World. Disney tried to fight the lawsuit with the defense that the man had signed a waiver for his Disney+ free trial years earlier. The waiver included terms and conditions with a statement in fine print that forced users to settle any disputes financially out-of-court. Disney’s rationale for being excluded was that the restaurant was owned by a third party, ignoring the fact that their arbitration clause with the Disney+ subscription covers over 150 million users.

What can be done about such difficult problems for everyday users of technology? For one, consumers can take personal responsibility in keeping their data secure by fully understanding the terms of collection they’re agreeing to. Although it is hard to tell when consumers sign up for popular social media apps, companies are almost always looking to gather profitable data from their users. And if they can’t do it outright, critics say they do it under the rug through site cookies and trackers.

In addition to Disney, many other companies have been using discrete tactics to steer away lawsuits that could harm the company. Walmart and Airbnb in particular use contracts with sweeping arbitration clauses to drag plaintiffs away from suing big corporations with legal disadvantages such as forced agreement outside of court. An arbitration clause legally forces signers to handle disputes with a company outside of court. This puts users at a disadvantage, since they’re unable to receive fair compensation for stolen data due to a contract most unknowingly signed.

In an interview with CNN, Creighton University Law Professor and arbitration expert Hossein Hossein Fazilatfar said, “The Average Joe in society doesn’t know what arbitration is, let alone understand the content of what they’re signing.”

Because the terms and conditions are usually so long, most people don’t bother to read them thoroughly or simply don’t read them at all. In fact, a 2017 study by Deloitte found that “91% of consumers accept the terms and conditions without reading them.”

How many students blindly agree to terms and conditions?

A Falcon-conducted poll of 49 students revealed that 94% of students habitually agree to terms and conditions, but less than 15% of these students read them thoroughly before agreeing.

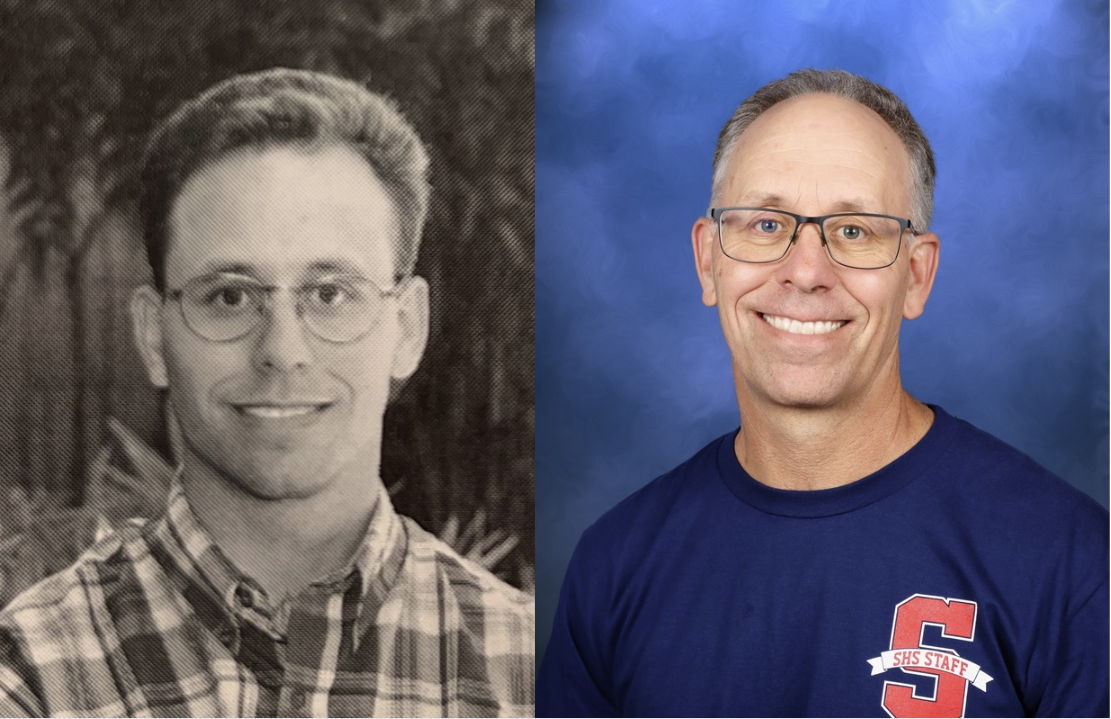

World History teacher Jerry Sheehy has been working to increase students’ awareness of data collection by large corporations, through his screening of the film “The Social Dilemma.” The Netflix documentary centers on the idea that there’s a moral quandary that concerns the ethics of data collection — to what extent should we allow data collection for advertising purposes? How can a just society extend this into the lives of children, who aren’t as aware of the implications of data collection.

While this is a major issue, there’s still debate over the correct way to mitigate the harms of data collection.

“The question is: How do we keep the good of this technology, and how do we start to deal with the bad? There has to be some regulation” Sheehy said.

Conclusion

As more people register accounts for social media platforms and apps, there is an increasing intolerance for blindly accepting pages and pages of terms of service. Companies repeatedly hide important agreements in fine print — agreements that will be useful to them in case a collection issue escalates to court. Data collection is supposed to be informed consent, but with everyday usage of the internet, many users fail to caution themselves from the dangers of monopolies disregarding regulations. Ultimately, experts advise making sure to read, or at the very least, watch reels about the sneaky terms you might be consenting to.

“The biggest thing I hope my students take away from [“The Social Dilemma”] is the importance of asking questions and being a critical thinker,” Sheehy said. “I think every social studies teacher hopes that their students leave their class thinking more critically, without taking things at face value.”