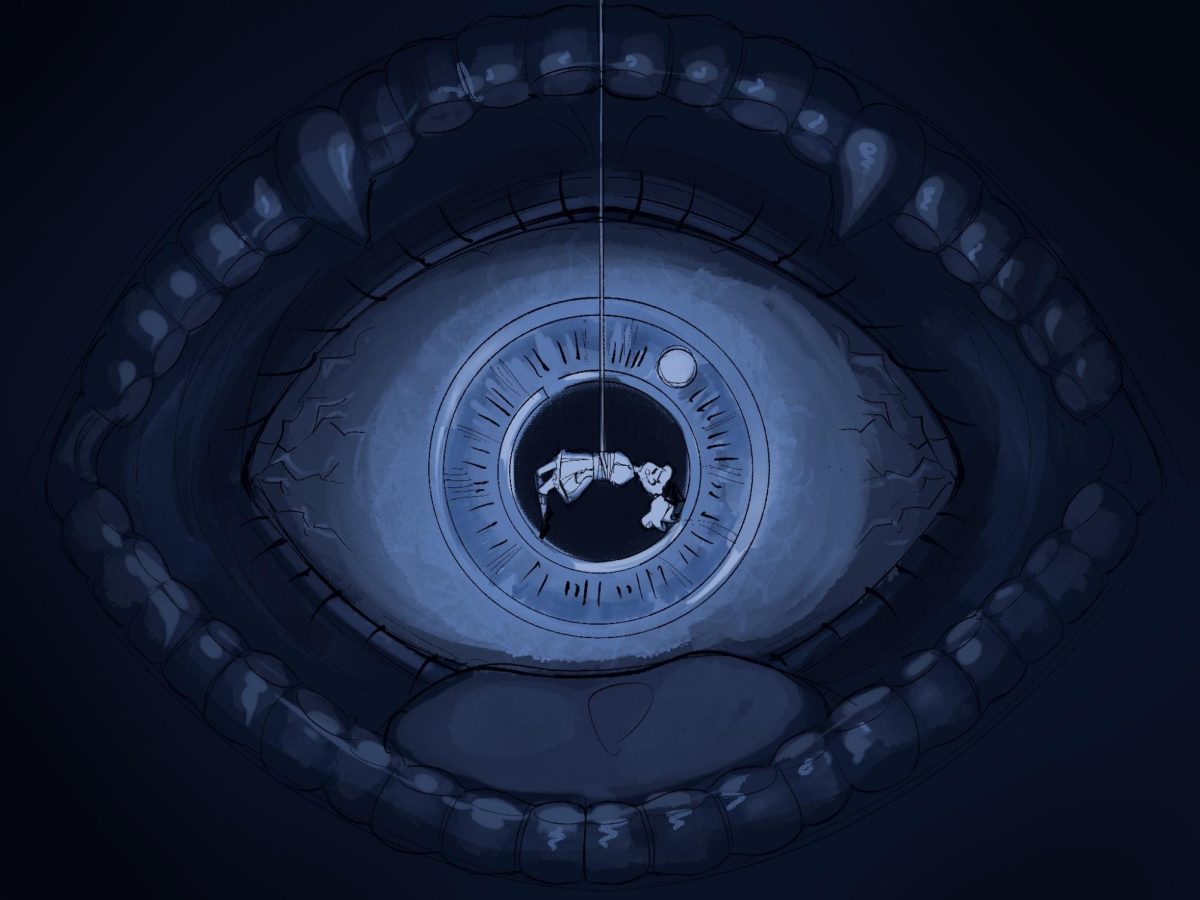

“Looks breedable” sits a comment emblazoned underneath an Instagram reel of a baby less than a year old. The comment has 5,242 likes. Just underneath it, someone commented, “Not my proudest nut,” a comment holding 229 likes. Switching over to TikTok, the comments under a video read “She kinda hot.” “Hear me out.” “There is no way that baby does not have a boyfriend.” The mother of the subject has identified her child as being 3 years old.

With the continual rise of fast-paced social media influencer culture, relying on going viral to earn large amounts of money is becoming an ever-more viable business strategy. Older Gen Zers have especially taken a liking to the trend — their experiences of growing up around technology allow them to still have their finger on the pulse of social media and many of them are at the age that allows them to thrive on the internet and make money through it.

And while some decide to pursue such a career option on their own, others have taken the alternative route of making their children the subjects of their social media campaigns instead.

To be sure, the phenomenon of family channels is nothing new. YouTube has countless famous family channels like ACE Family, The Bee Family and Roman Atwood Vlogs, which have shown parents aspiring for internet fame proudly showing off their young children to tens of flashing cameras.

In recent years, however, short-form content has come to dominate the media landscape. Parents aspiring for internet stardom have pivoted from using the relatively moderated, edited and scripted lands of YouTube to the form of parent-owned and child-run Instagram and TikTok accounts, which thrive on more consistent interpersonal exchanges in story threads and comment sections. The children (some as young as 2) do collaborations, advertise brands and face the ever-brutal lashing of internet scrutiny that used to be reserved for celebrities twice their age.

Even more problems arise when the actual target audience for such child content is considered. As The New York Times has reported, child influencer content that is sexually suggestive in nature is the most likely to get engagement on Instagram compared to any other kind of child content. Such posts sport an audience of mostly older men. Why else would a large crowd of adults engage with content of children on social media, really?

For parents who are already determined to succeed in such a field, it’s very easy to notice such a preference and follow the trend in hopes to attract more attention, boost the account’s viewership, get brand deals for their child and grow their fortune even more. After all, social media works quickly, influencers always follow the popular trends to grow their viewership, why shouldn’t child influencers do the same?

So, in effect, these parents are choosing to lean into the trend even more, posting more suggestive content of their children so their follower counts grow and they’re able to access more opportunities. Or they reject the trend and the men come to their page regardless — after all, it’s been normalized so much already. More predators have been attracted to the site and they will consume and infestate the communities of even the more innocent child content.

And even if the parents never exploit their child explicitly for money, the normalization of the culture of oversharing on social media has been present with Gen Z parents long enough while they were growing up that now they feel no hesitation at exposing their children’s most private lives on Instagram. Their first day of school, their first period, even their birth could be cataloged for millions of strangers to witness without the child’s consent. The cycle of unhealthy, unrestricted internet voyeurism continues with little to no intervention.

None of this is helped by the reporting feature on social media (at least for Meta), which has also been found to be an absolute joke with limited block features. This feature essentially leads to a child account being met with an onslaught of pedophiles. Even if the parent takes time to individually block each and every inappropriate comment, they will remain on the page since no account can block too many people in one day.

Really, a majority of parents who try to go down the path of making their child a social media influencer are already working with a certain type of business-oriented mindset, viewing their child as a product and agreeing to sacrifice certain comforts of the child in exchange for profit.

The life of an influencer is difficult, even more so when they’re working with a brain that isn’t fully developed. Kids are easily impressionable — they only see the fact that their parents are influencers and receive a lot of attention, or only see the lavish, glamorous life of influencers and might be unaware of social media’s consequences.

Children who seriously go down the route of influencing have to adopt certain standards for themselves — being their own PR team, learning to respond to online hate, always looking presentable, having to manage a professional schedule when it comes to brand deals, photoshoots and fashion events.

And of course, doing everything to please their audience of creepy grown men online so they don’t leave and potentially make their numbers fall.

It’s strange how child influencing, which utilizes social media heavily and interferes with their brain development, robbing them of their childhood, doesn’t legally fall into the category of child labor. Only one state, Illinois, even requires the parents to monetarily compensate their child for their services, and even then they’re only required to allot them 15% of the total earnings.

State and federal lawmakers need to start doing something about these disturbing accounts. Meta reporting protocols for child safety (which Meta claimed wasn’t even a priority of theirs, mind you) should be taken WAY more seriously to crack down on predators, and parents of child influencers need to start being held accountable for the exploitative content of their children and afford these children an actual childhood.