On Dec. 6, 2023, Simon Armendariz, 23 at the time, was formally sentenced to 12 years in prison for selling fentanyl-laced pills to a group of Los Gatos High students.

In the past decade, there have been multiple fentanyl-related deaths in Los Gatos-Saratoga Union High School District (LGSUHSD): All were from Los Gatos High School. This was just one of many incidents in what the CDC deems an alarming nationwide opioid epidemic. Fentanyl, a highly addictive synthetic opioid, was responsible for the deaths of two-thirds of approximately 106,700 people who suffered drug-related deaths in 2021.

According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, fentanyl’s primary function is to serve as a severe painkiller and is “approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin.” Its addictive quality has led drug dealers across the country to begin adding small amounts of fentanyl to other drugs such as Marijuana, said Leslie Gentry, a local anti-fentanyl advocate. The more fentanyl added, the more addictive the drug is. And the more addictive the drug is, the more drug dealers are likely to profit.

While fentanyl is almost always safe for use in controlled environments such as a hospital, exceeding a certain dosage is often lethal. Depending on a person’s weight, past usage of the drug and inherent tolerance, even 2 milligrams can be deadly. To show how small this is, one teaspoon is roughly 5,000 milligrams.

Fentanyl plagues the U.S. with an upshot in teen and young adult overdoses

The current skyrocketing rate of drug overdose death tolls across the nation has been called the “fourth wave” of opioid overdoses. A recent study by UCLA revealed that the fourth wave began in 2015, marked by the rise of fentanyl use in tandem with other stimulants and drugs.

The study also noted that fentanyl addiction disproportionately affects teenagers — a majority of deaths caused by the fourth wave were those in the age range of 15-24.

In response to the rise of opioid overdoses in 2023, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Narcan, a brand name version of naloxone (a nasal spray that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose), to be sold over the counter in March 2023. Additionally, last September, president Biden approved a $450 million subsidy effort aimed at fighting the fentanyl crisis.

The money will be spent on prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery services, as well as cracking down on drug trafficking, White House domestic policy advisor Neera Tanden told Bloomberg in August.

The subsidy is split into three distinct components: $80 million to expand overdose treatment sites in rural areas and the distribution of naloxone, $58 million in expanding recovery support with expansions in mental health care and housing services and $19 million in fighting against fentanyl trafficking.

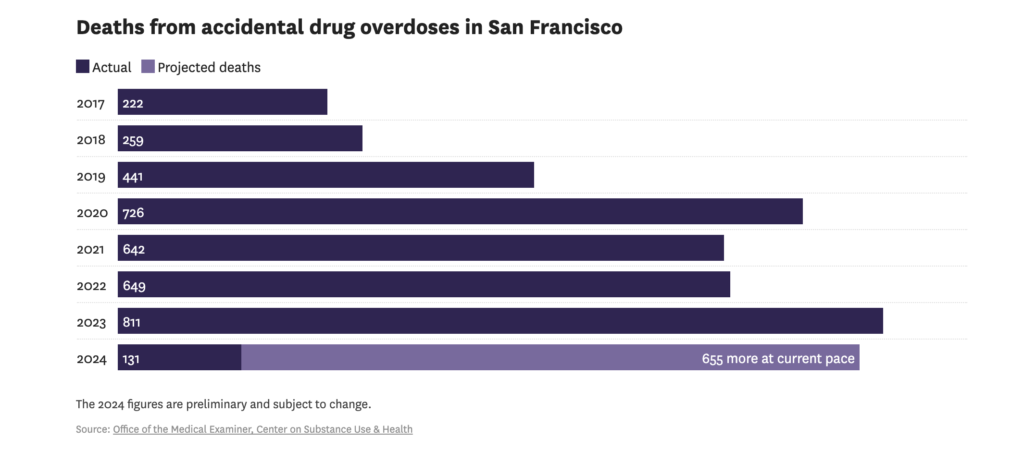

In California, the fentanyl epidemic is especially prevalent in big cities like San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles. According to data from the California Overdose Surveillance Dashboard, nearly 6,000 Californians died from fentanyl overdoses in 2021. The San Francisco Chronicle has reported 73% of overdoses during 2020 that happened in San Francisco were due to fentanyl. Additionally, 1 of 25 of the deaths were under 19.

Moreover, in 2022, fentanyl was responsible for nearly 97% of opioid-overdose deaths for 15- to 19-year-olds in California — and over 80% of all drug-overdose deaths for that age group.

In response to these growing death tolls, in March 2023, California governor Gavin Newsom OK’d spending $1 billion to address the crisis. The largest portion of this money will be spent on distributing Narcan to California communities.

LGSUHSD addresses its emerging fentanyl problem

In Santa Clara County, officials are also targeting the epidemic, as demonstrated by Armendariz’s arrest and sentence.

“Just so everybody knows: fentanyl kills,” Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen said in a press release after Armendariz was charged in court. “If you sell fentanyl to teenagers, then our prosecutors will do everything in our power to send you to prison for a very long time.”

In addition, Santa Clara County has set up the Santa Clara County Opioid Overdose Prevention Project, which aims to raise awareness about the fentanyl problem and educate citizens on how to safely treat opioid overdoses. The coalition, composed of medical professionals and local volunteers, currently has multiple initiatives to help curb the opioid epidemic, including a free mail-in Naloxone training program and the establishment of Community Mobile Response Teams that work to educate and assist families.

The district has also taken a stand in informing and protecting students and parents. The district has hosted multiple meetings on how to administer Narcan, with one on Dec. 12 for parents and two during tutorial on Feb. 27 and 28 for students.

As further precautionary measure, district nurse Lisa Tripp led a training for every district teacher on how to administer Narcan to students suffering an overdose. The district has also restocked every AED cabinet on both campuses with Narcan kits and instructed every teacher to keep a case of Narcan in their classroom at all times.

“The district explored opportunities to train our staff last year, which we did,” Tripp said. “And I believe that we were the first district in Santa Clara County to train the entire staff and provide them with Narcan.”

After seeing the proliferating problem, the district has made efforts to curb the problem before it results in more deaths. According to Tripp, one of the driving factors of her employment was the district’s goal to keep students safe in the face of overwhelming fentanyl dangers for teens.

LGSUHSD community responds to fentanyl overdoses

Some SHS students have also experimented with drugs, including opioids like fentanyl and stimulants like ecstasy, also known as molly. Sometimes, even when a student believes that they are doing a less lethal drug — such as marijuana or Adderall — the drugs may be laced with stronger opioids One SHS student who requested anonymity recounted a normal Friday night in November, just like the previous few weeks, where they had met with their friends in an undisclosed location to hang out.

“I was using my friend’s [weed] pen and I took a few hits and it usually takes 20-30 minutes to hit,” the student said. “I felt my eyes blacking out, and seeing weird visions.”

The student described being in a sense of delirium, as they were not able to tell where they were and fell in and out of consciousness. Friends around them noted their erratic breathing, slurring and incomprehensible speech.

“So at one point I started trying to get home, but I couldn’t figure out what to do and my friends weren’t able to help me,” the student said. “I was fading in and out of consciousness and could not think clearly.”

The student noted how crucial it was that their older sister was in town, as she was able to pick them up and watch over them until they were safe again.

“My sibling was the only reason I made it out that day safely,” the student said. “She knew how to take care of me and make sure I didn’t accidentally hurt myself and got home safely.”

The student is unsure as to what their friend’s pen was laced with, but due to their symptoms, it could have been a trace amount of fentanyl or ecstasy.

“It’s scary because I was using the pen of someone I knew decently well,” the student said. “After I got home, I could not sleep because I kept breathing erratically and felt my heart pounding out of my chest.”

The student’s story is not unique for current high school students — less lethal drugs can be laced with opioids like fentanyl, unbeknownst to their users. Fortunately for this student, they were able to recover to full health within a few days and never needed medical treatment.

With the impact of fentanyl on the Los Gatos High community specifically, one senior at Los Gatos High, Kyle Santoro, researched and directed his own full-length documentary film called “Fentanyl High.” The film explores the impact of fentanyl on different schools in Santa Clara County and gives ideas for reforms that need to be made to protect students from the dangers of fentanyl. It is currently being screened selectively at theaters across the Bay Area.

Los Gatos family’s tragic loss

The Gentry family is a Los Gatos family who has gone public about their 22-year-old son, Jolly Jones, and his death as a result of a fentanyl overdose in 2021. After sustaining a major football injury when he was 15, he became addicted to street pills to help ease the pain from the injury. In July 2021, he had been experiencing opioid withdrawals and unfortunately died on the third night of his fentanyl detox. Since then, his mother Leslie Gentry has become an advocate in hopes of raising awareness in the community, setting up a yearly run for awareness called the Jolly 10K.

Gentry believes one of the most critical ways to help slow the effects of the fentanyl crisis is by raising awareness.

“The purpose is so that I could raise money to do more outreach because there’s not much outreach, and I’m trying to figure out a way to get more young people involved — or go to the schools and talk to the kids about the realities of fentanyl,” Gentry told The Falcon. “The realities of the fact [are] that [current students] don’t have an opportunity anymore as kids to experiment and learn from your mistakes.”

By working to raise awareness in her community, Gentry believes that people will be able to be safer while taking drugs — with better knowledge of the dangers of fentanyl and greater accessibility to Narcan, she hopes that others will be able to avoid fatal overdoses.

“What I wish my son would have known is that you can go into certain places like, San Jose or Santa Clara University and get Narcan,” Gentry said.

Gentry points out that students can get Narcan, even without parent knowledge and consent, through town jails or local universities. She also stresses that students should not be afraid to call emergency services in the case of an overdose.

“If you call 911 to get an ambulance for a friend who has overdosed, you will not get into trouble, even if you are under the influence, even if you are a minor,” Gentry said. “You may get into trouble with your parents, but not the police.”

****

If you or someone you know is struggling with substance abuse, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.