In engineering teacher Audrey Warmuth’s Engineering Design and Development (EDD) classroom, seniors crowd over their high tables, putting together a flurry of different capstone projects. After taking at least two of the four preceding engineering courses — STEM Lab, Principles of Engineering, Digital Electronics or AP Computer Science A — seniors finally get to take the reins of their everyday EDD classes, by building largely self-directed innovations.

From an interactive riverbed display to electrode pads that emulate the feeling of resistance when interacting with virtual reality (VR) objects, the class’s final project is a one-of-a-kind activity allowing students to put the culmination of their engineering knowledge, acquired from the school’s comprehensive engineering track, to the test.

Warmuth guides and empower her students to build their own project

The project — set to finish with a poster presentation in May — started around Thanksgiving when seniors came up with their own preliminary ideas for what they wanted to build. Many drew inspiration from Warmuth’s recommended website “Instructables.”

They then presented a list of potential ideas they found in their research and grouped up with up to three other students who had compatible skills for their desired projects.

As students began building their projects, Warmuth said she took a backseat on their projects in order to let students take the helm. In each class, students and their groups work on their projects individually. Warmuth’s main role is to ensure their timeline is feasible, monitor students’ progress and provide any technical assistance needed. To keep track of the overwhelming number of projects in the class, Warmuth keeps a spreadsheet of each one and frequently updates the information for each group through her daily progress check-ins.

“I feel like I’m their boss, but the big difference is that they have to drive the projects themselves,” Warmuth said. “I tell the students they need to build in certain milestones that they want to achieve. Often [students] want some big project, but sometimes to achieve that is really difficult. So [I ask]: ‘Is there a prototype that you could do? Is there a part of a prototype that you can achieve?’”

Warmuth notes that her check-ins with students mirror how managers in tech companies collaborate with their employees.

Nevertheless, Warmuth notes that there is a definitive difference between industry engineers and students, because of the class’s budget and time restrictions. By the project requirements, each group’s members are limited to contributing $40 each to their group’s total project budget and lack much of the resources and time that comes with a professional career in tech.

However, Warmuth still believes that the project drives students to achieve a goal beyond good grades that can help them be successful in their future careers. She believes that, by allowing students to define their own targets, the class mimics real life.

“I find I’m often surprised by students,” Warmuth said. “You don’t have to be a straight A student to be an A student in the class. To me, if you’re the type of person who has a vision and your interests related, you can be successful in the classroom.”

Seniors Sam Kau, Eric Shi and Levaunt Chen tackle constructing a riverbed table

After finding inspiration on Instagram and videos on YouTube, seniors Levaunt Chen, Sam Kau and Eric Shi decided to create a riverbed table, which is a decorative table with touch sensors that light up by a waving movement of the hand. With just a clap of their hands, a dark room like a restroom can immediately light up.

From this project, Kau said that the group learned a lot about how to manage their budget of around $40 per person. As they have worked to carefully place and solder together tiny touch sensors in their desired place, the group has already run through a pack of 20 TTP223 touch sensors, and plans on ordering up to 100 more.

While the group experienced many trials and errors throughout the project, Kau said that they were able to improve the placement of their sensors.

“A lot of our problems were dealing with hardware, wiring and coding. We had to figure out how to extend the range of the touch sensor to correctly orientate our wires,” Kau said. “But, we hope to finish soon because we just need to assemble everything.”

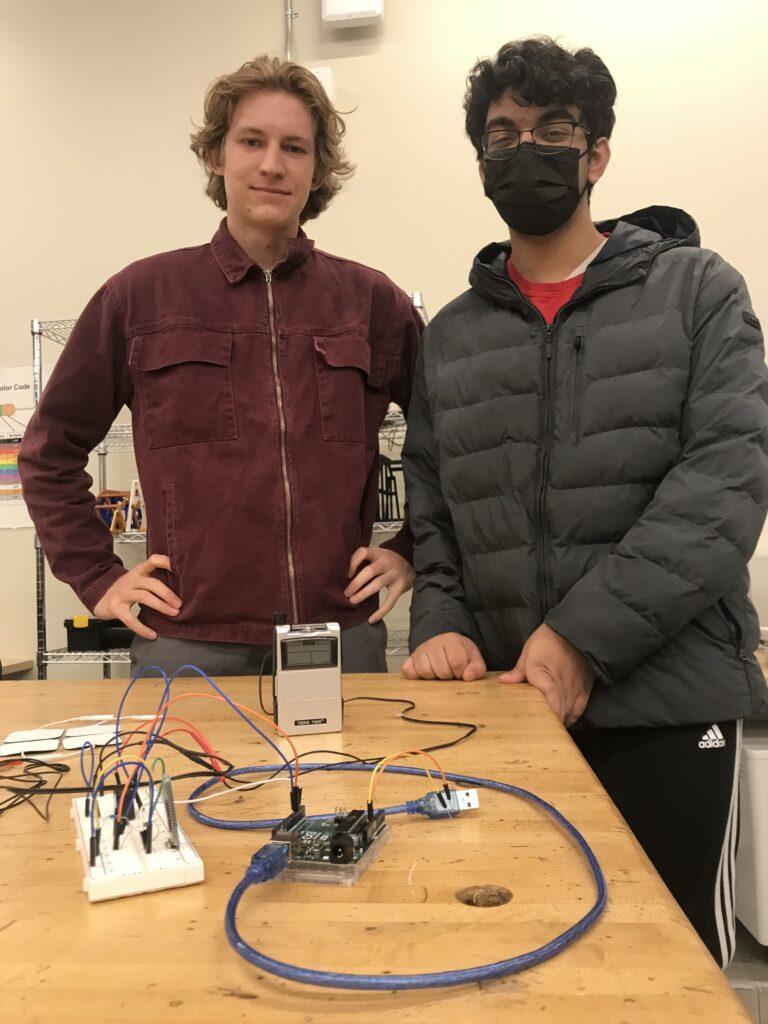

Two seniors create a tactile response machine to pair with the new Apple Vision Pro

When senior Eric Norris presented his idea to use Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve (TENs) pads to simulate the physical touch with VR objects to the class, senior Sreyash Das Sarma picked up on the idea’s potential and compatibility with his own idea for a prosthetic arm. The two decided to combine their hardware, software and anatomy knowledge to bring the project to life.

“We both had our respective ideas a long time ago — maybe like two years ago,” Norris said. “But this is the first time that I was able to actually delegate time to work on it. This class gave us an opportunity to not only work together but to really pursue our ideas.”

TENs units are electrode pads generally used in physical therapy to create a tingling sensation that relaxes muscles and relieves pain — the application by which Norris, undergoing physical therapy with TENs units after breaking his arm, was inspired by. However, Das Sarma and Norris are using them to stimulate muscles and nerves in the area to make the body think that it is receiving electrical stimulation from the brain. This way, TENs units can be used to control muscles, such as in the arm, to force the limb to respond as if met with resistance.

“The concept behind it is every action the body can do has an opposite reaction,” Norris said. “We like to think of it like every muscle in your body has an antagonist muscle, so if you activate your antagonist muscle at the same time you try to perform an action, you can create the feeling of resistance — like when grabbing an object.”

The pair is able to stay under budget by wiring everything themselves, using Norris’s Apple Vision Pro (a virtual reality headset) and buying cheap electrode pads. However, they have struggled to connect to the goggles using WiFi Direct Connect, and instead opted for Bluetooth and Apple’s XCode program — where developers can custom-write their own programs to use information from the headset.

So far, the two have been able to activate the TENs unit using their own vision recognition model to find the distance between the thumb and index fingers squishing the imaginary ball — and, now that the Vision Pro has been released, are moving towards using that instead.

They have also filed for a provisional patent, specifically for using the TENs unit to create resistant feedback.

“People thought about using TENs units to create a tingling feeling,” Norris said. “But nobody’s used it to actually create physical resistance. So we’re stoked about that.”

They are also looking to improve the machine’s features, by expanding into touch sensations on the fingertips and adding variable intensity to the TENs unit. To simulate touch sensation, they plan to stimulate the ulnar and medial nerves on the wrist by changing the position of the electrode pads.

“So by controlling how much you’re actually stimulating each muscle, you can — specifically for the ulnar and medial nerve — control what you feel and how hard the object might be,” Das Sharma said.

The two see the project extending even into college, because they believe that it has the potential to continue improving — and that VR will not stay as a technology with only intangible pixels.

They believe that Warmuth’s contribution to their class and their project has made a great impact on them, both in keeping their project on track and providing technical help.

“She’s great at giving a reality check because a lot of students have really ambitious ideas,” Norris said. “She’s great at listening to your ideas and telling you what you might be able to do — and from there, you can make really educated decisions about what you want to do.”