Rating: 5/5 Falcons

“‘But the old people are hard to change their minds.”

“It is hard to change the minds of the old,” corrected Duncan automatically.

“It is hard to change the minds of the old,” repeated William. “It is hard to change the minds of the old.’” (Jen).

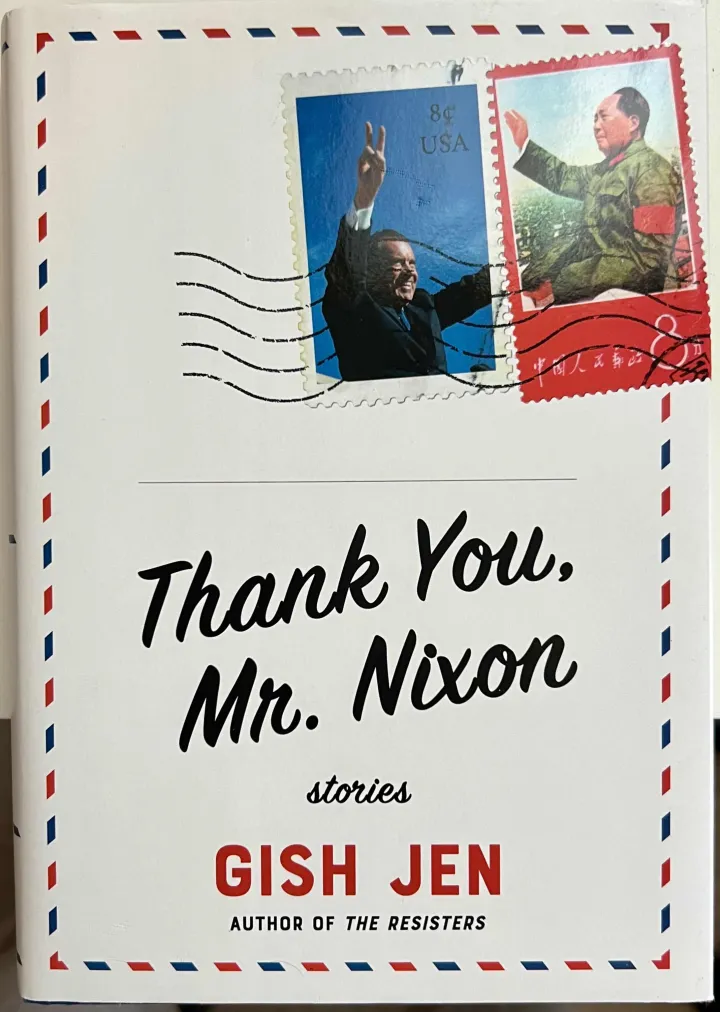

I couldn’t erase that short snippet of dialogue from my memory even after I’d left the page in the third chapter, flipping faster and faster through “Thank You, Mr. Nixon,” Gish Jen’s 2022 retelling of China’s recent history, her eyes peering through the eyes of fictional individuals who experienced factual timelines.

I read the book based on a recommendation by my English 11H teacher Amy Keys last year. She may have been hoping I’d discuss the contents with her soon after, but I was too embarrassed to confess that I had hardly started it months after she gave me the idea of the title. Recently, though, I accomplished this leftover goal from junior year.

“Thank You, Mr. Nixon” follows 11 individuals who, for the most part, unknowingly play roles within each other’s lives. Through this piece of commentary on society and interconnectedness even prior to the internet, Jen illustrates human connection through personal relationships as well as the history that binds us.

‘Thank You, Mr. Nixon’ — a message from heaven

The story begins with a letter from a Chinese girl in heaven, writing to President Nixon in hell and thanking him for his groundbreaking visit to China in 1972. She is grateful for the irreversible change that gripped the nation and shifted its international relations permanently — not to mention the vivid-colored clothes such as a red coat worn by his wife Pat, which in turn became a symbol for change and thawing U.S-China relations. Already Jen weaves in witty comments that characterize the narrator and politicize satire, even while she details the early stigma surrounding products manufactured in China, or the horrifically immeasurable deaths Chairman Mao was responsible for, or concepts of heaven and hell that sound oddly similar to regular life anyway. It serves as an blank-slate introduction, the book’s outlined tabula rasa.

‘It’s the Great Wall!’

‘It’s The Great Wall!’ is a chapter told from the perspectives of Grace Chen de Castro, her Caribbean Sephardic Jewish husband Gideon, and Grace’s mother Opal; the trio are participating in a China tour with an inept guide, so Opal serves as the group’s translator. She hasn’t returned to China in 40 years and is visiting her relatives. Thus, she struggles both with translating Chinese ideologies and concepts to the comparatively close-minded tour members as well as the emotionally charged reunion with her family.

I found myself relating quite a bit to Opal’s predicament. I’m often tasked with explaining difficult English words or idioms to my grandparents, who are fluent only in Cantonese and Mandarin. I, too, wonder how different Hong Kong will be from the snapshots I have of growing up there: the freeze-frames of weeping leaves and roots gripping mossy walls, of friendly grandmothers and uncles bagging flopping fish in the street markets, of the silent public library’s strange, old-paper smell (one my mother hated, and I secretly loved).

These thoughts definitely returned to me as Jen described sideways monsoon rains, and the unobstructed view of a lush, quiet mountain peak through an apartment window — as if she could see through me! I am still shocked by how closely these words mirrored the memories I have of home.

The chapter closes with a vision of Opal’s mother telling her she will serve as a translator for the rest of her life. Effectively, she’s the bridge between the two countries and their cultures, personal choice disregarded.

‘Lulu in Exile’

A relatively shorter chapter around the middle of the book, these four pages describe the duality of Chinese culture’s expectations of women through the perspective of Lulu. Her boyfriend’s mother expects her to maintain a model’s body, criticizing the large clothing she wears by calling it “horse-like,” while also shoving desserts onto the girl’s unwilling plate. Needless to say, Lulu falls out of love with him and his family quite quickly.

This experience is pretty universal; older relatives and acquaintances will judge their juniors, deeming age as a measurement of maturity and wisdom. Oftentimes the “advice” is less helpful than intended. Jen communicated Lulu’s despair so vividly that those mere paragraphs hurt a little to read.

‘Amaryllis’

Personally, this chapter by far stands out among the narratives. The now grown-up daughter of the aforementioned Grace and Gideon, Amaryllis, has to care for her friend Tara’s grandfather while she’s off doing charity work outside the country. No one in his family wants to waste their precious time on him so the responsibility falls on a stranger.

She at first is a little awkward around him, perceiving herself as an outsider and his silence, even in her presence, exacerbates this. One day, though, they talk for the first time in his doorway (undoubtedly symbolic), and from there she begins to see him as her own family. Amaryllis, through making food for him and waiting for him at the station in case he gets lost, becomes incredibly close with him — she leaves work early to tend to his needs sooner, making room in her life for him.

At the start of the chapter, Tara specifically tells Amaryllis not to bathe him. Out of compassion, and a bit of curiosity, she ends up offering to do so after dinner one night. Nearly crying in the bath remembering, he recalls that his late wife used to bathe him. Amaryllis is stunned in witnessing the life buried within someone she considered so close to death.

However, she’s still worried that his mental state isn’t good enough to be left alone, so she contacts Tara’s family members. Tara’s brother comes by, but instead of expressing any concern for his grandfather, he complains that Amaryllis made a big deal out of nothing; in her anger at his selfishness, she reluctantly yet decisively leaves the apartment, and that shred of living history she tried so hard to preserve, behind.

Jen’s writing in the novel is phenomenal. It artfully captures the distinct voices of separate narrators without speaking in the first-person, save for the first chapter, written as a letter. She illustrates human flaws and kindnesses, their intentions and accidents, nearly to a fault (I say nearly, when really I would never tire reading of them); if a certain person is meant to be ignorant of Chinese culture, she carves depth beyond mere stupidity — their acknowledgement of what knowledge they lack, or a separate endearing facet to their personality that makes them difficult to dislike — and thus makes otherwise ordinary characters compellingly memorable.

Jen even captures her own struggle with interdependent qualities and her pursuit of the humanities. It parallels the Cultural Revolution’s destruction of the Four Olds with America’s current erasure of Chinese Americans hoping to study the arts while facing the challenges of capturing abstractism in their non-native tongue or living off the meager wages they manage to earn. “Thank You, Mr. Nixon” starts with 11, but branches out to so much more than just a microcosm of connected strangers.