Aged hands roll over sticky anise cookie dough as the afternoon sunlight casts a stream across the kitchen countertop. Senior Hannah Dimock stands beside her grandmother, Mary Wong, 86, watching intently over her shoulders. Across the room, Hannah’s mother, Sharon Palmer, slides a fresh-baked tray out of the oven just as her father sneaks a bite.

This image parallels one decades earlier during the Great Depression: In a smaller home situated within a largely white community in Beloit, Wisconsin, Hannah’s great-grandmother Yee Shee stood in her kitchen as the neighboring Antonsen family from Sweden taught her a recipe that would eventually be passed down to her children and become beloved by all her future generations.

Yee Shee was a first-generation immigrant who, at age 29 and in an arranged marriage, moved from Guangdong, China, to the U.S. in 1923. Despite the prevailing societal pressures and expectations as a single mother for Yee Shee to return to her homeland with her children in the late ‘30s, she chose to stay put and single-handedly raised seven successful kids.

These rich family traditions and history, coupled with Hannah’s own experiences in an Asian American majority environment like Saratoga and her scholarly discussions with her father Andrew Dimock, who previously taught English at Saratoga, have all contributed to her understanding of her cultural identity. While Hannah is a quarter Chinese, she identifies as fully white.

“I’m aware of the fact that I appear fully white to other people. In that sense, I think I’ve internalized the idea that I can’t consider myself anything but white, given that the percentage of my genetic makeup that’s Asian is, comparison-wise, quite small,” she said. “When I mention that I’m a quarter Chinese, it feels like I’m grasping at something that’s barely there, to somehow prove that I’m less white than I’m being viewed as.”

Even so, she is heavily involved in and inspired by her family’s traditions, such as their annual family reunion and the inspiring immigrant story of her great-grandmother, Yee Shee.

In the Depression days of Hannah’s great-grandmother, Mary and her older siblings Helen, Harry and Frank entertained themselves by watching their mother cook, but there was no father in the room. In 1938, Yee Shee’s husband, Charles Wong, died at age 46 while trying to prevent a brawl in their family restaurant, the Nan King Lo. Despite being beloved by the community, the restaurant was later sold by Yee Shee to support her children financially.

Now, almost a century later, Yee Shee’s story has been captured by Mary Wong and Beatrice McKenzie — an emeritus professor of history at Beloit College — in the 2022 book “The Wongs of Beloit, Wisconsin.” The book traces 13 generations of Hannah’s family history.

Four generations removed from Yee Shee’s journey and struggles in the U.S., Hannah sees herself carrying on the traditional values her ancestors brought to America, while also shaping them through her first-hand experience watching her first or second-generation immigrant peers go through the cultural translation process. Hannah has shifted her ancestors’ traditional values to focus more on individual interests and freedom to explore her passions.

“Understanding the immigration and assimilation process has made me more conscious of the differences between the experiences and familial situations between myself and my classmates,” Hannah said. “I have the unique experience of growing up in an environment where white people are in the racial minority. I try my best to use this experience to be more mindful of my own privilege as a white American and inform the importance of carrying on the stories of my family’s assimilation into the United States.”

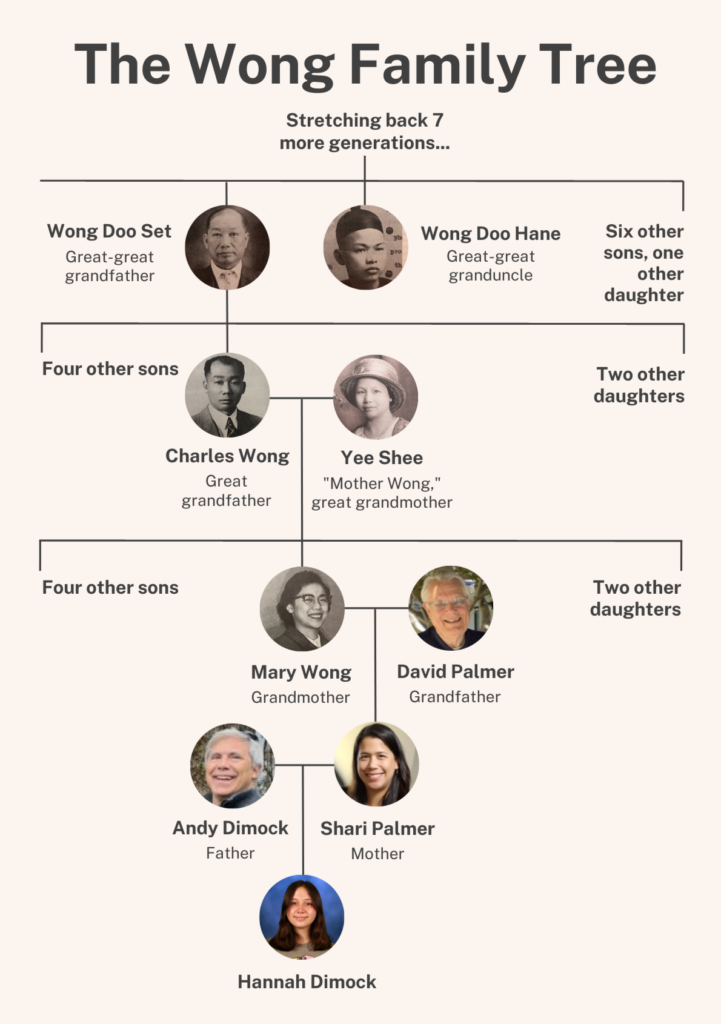

The Wong generations, starring:

Graphic by Lynn Dai, Photos Courtesy of Hannah Dimock

1st generation: Wong Doo Set, great-great-grandfather; Wong Ben Yuk, great-great-uncle

2nd generation: Charles Wong, great-grandfather; Yee Shee “Mother Wong,” great-grandmother

3rd generation: David Palmer, grandfather; Mary Wong, grandmother

4th generation: Shari Palmer, mother; Andy Dimock, father

5th generation: Hannah Dimock, senior; Katie Dimock, Class of 2021 alumna

Yee Shee: establishing traditions, defying stereotypes

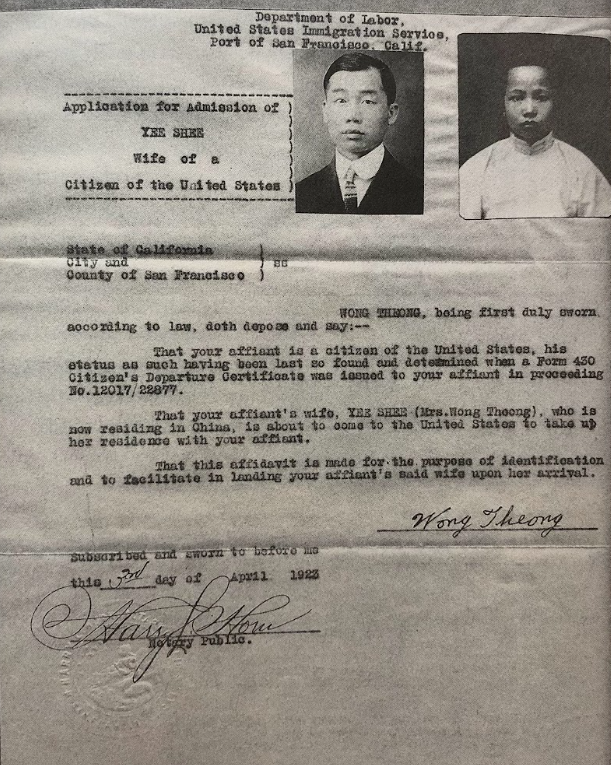

Yee Shee’s journey to Beloit in 1923 with her husband Charles Wong, was primarily motivated by the unstable political tension in Guangdong and the looming threat that Congress was about to tighten immigration laws and permanently declare wives of citizens “ineligible to naturalize” as U.S. citizens. In Beloit, “integration services” including workforce education and English language and literacy classes were provided for the immigrant population.

Courtesy of NARA San Bruno

Charles Wong’s application for Yee Shee’s immigration in 1923.

Charles Wong was a dedicated business owner of his family’s Nan King Lo restaurant and a “family man,” according to Mary. Through his goal of providing a better education and life for his children, he placed heavy emphasis on assimilating his children into Beloit through weekly sessions at the local church.

“The church provided the support of a known, repetitive, supportive activity and was a place with friends, including one friend my age, with whom I continue to keep in contact,” Mary said.

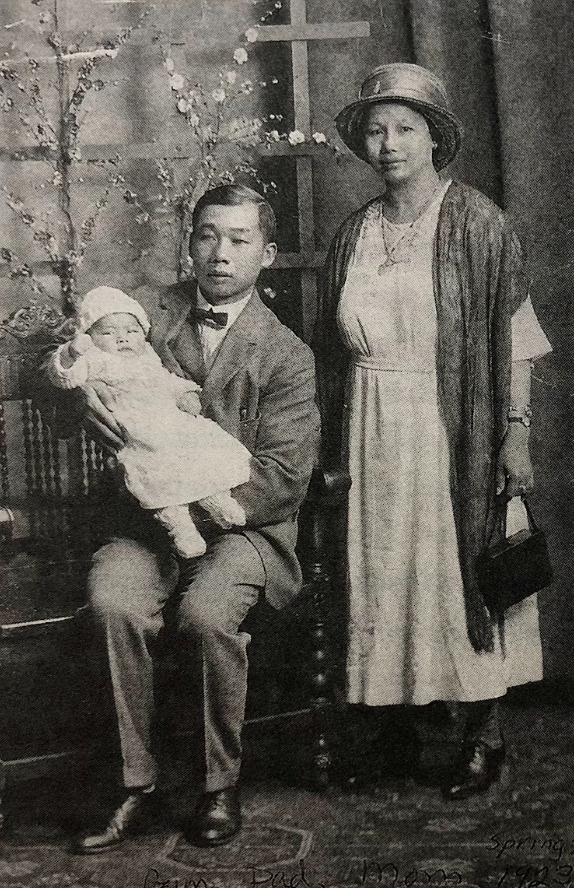

Courtesy of Fung Scholz

A family photo of Charles Wong, Yee Shee, and their son Gim Wong.

After her husband’s unexpected death, Yee Shee chose to stay in America while also keeping alive bonds with family in China.

Mary Wong said an important factor that encouraged Yee Shee to stay might have been her desire to carry out her husband’s goals. Although such characteristics in a patriarchal society often diminish the role of women — Confucian teachings emphasized that women were always to obey their husbands, and after they died, their sons — Yee Shee drew on connections she had cultivated in her community, using them to fuel her efforts to keep her family in the U.S.

“Women in an arranged marriage such as my Mom, accepted and followed their husband’s lead,” Mary Wong said. “Since my Mom knew why they immigrated to the U.S. Midwest, she felt she needed to fulfill his goals no matter how difficult and she saw how successful her oldest children were in school and community.”

Yee Shee had no mother, sister or close friends to share her work, as she would have in China. Still, with support from her neighbors, she cooked every meal, cleaned, sewed, washed, ironed and mended clothes and established a small successful garden in her backyard, all while maintaining a strong image for her children.

“As I was 17 months old at the time, I was not aware of how great her grief was [after Charles’ death], wailing and crying so my older siblings and neighbors sadly remembered,” Mary Wong said. “I did, upon reflecting, realize that as I got older, the only time she seemed sad was on or about the anniversary date of my father’s death. Otherwise, she had a pleasant disposition, working hard each day to complete her work, never complaining.”

With her seven children, Yee Shee managed to pass on traditional family values. Among those values were a respect for elders, frugality and helping others in times of need. During the Great Depression, for example, Yee Shee shared her garden bounties with the neighbors. To keep food on the table, she sold shares of the family property in Hong Kong.

After the U.S. repealed the Chinese exclusion laws that significantly restricted immigration to the country from 1882 throughout World War II, Chinese citizens became eligible for naturalization. Consequently, Yee Shee naturalized as an American citizen in 1959. She utilized her citizenship to her advantage, frequently visiting children and grandchildren in California, Washington, Pennsylvania and Utah. Before her death in 1978 at age 83, Yee Shee had 22 grandchildren and was able to remember all their birthdays.

Moreover, her seven children all grew up to lead successful lives. Gim Wong, the eldest, was a staff sergeant in World War II, later became a plant engineering manager at Fairbanks Morse & Co., and was awarded “Beloit Booster of the Year” in 1971 for his involvement in community service; Fung Wong was a registered nurse and helped open the first emergency room in Beloit, in 1948; George Wong was a First Lieutenant stationed in Korea in the ‘50s, and later became an electrical engineer at Beloit Iron Works (now Beloit Corporation); Helen Wong started an international women’s club at Pullman; Harry Wong was a cardiac anesthesiologist and opened Utah’s first ambulatory surgical facility, later teaching at the University of Utah Medical School for many years before becoming honored as the Presidential Endowed Chair in Anesthesiology; Frank Wong earned a full 4-year scholarship to Harvard University and later became a professor of history, dean, provost and vice president at several colleges and was a member of the Board of Directors of the American Association of Colleges and Universities; and Mary Wong, the youngest, went on to become a teacher, sometimes being the only minority to hold the role in her schools.

Mary Wong’s brother, Frank, likened his mother to a “Golden Chrysanthemum,” referencing the symbolic flower in Chinese culture that represents strength and unchanging virtue through a flower that survives the deathly frost of autumn.

“So successfully had Yee Shee overcome the extraordinary circumstances of her life, including outrageous misfortune, that to those close to her, time seemed to have no grip on her destiny,” Frank wrote in his eulogy included in the book. “Although she accomplished most of her life in America, she did so with simple Chinese virtues that are also universal virtues; courage and compassion, strength and love, honesty and justice, all nourished by the extended roots of the family. Neither time nor death shall conquer these.”

Current generations: carrying on familial legacy

While Mary and her six siblings often faced the difficult balancing act of integrating American values of individualism and competition with the traditional values established by Yee Shee, she has always remained true to her family values.

Throughout Mary’s life, the values of hard work, honor, respect and generosity taught by Yee Shee were at the heart of how she and her siblings tried to live their lives and also pass down to their children.

She now lives with her granddaughter Hannah, her daughter Sharon Palmer, the senior associate vice provost for undergraduate education at Stanford University, and her son-in-law, Andrew Dimock. Andrew Dimock is teaching at Branham High School this year while occasionally substitute teaching here; he previously taught English 9 and 10 as a long-term substitute.

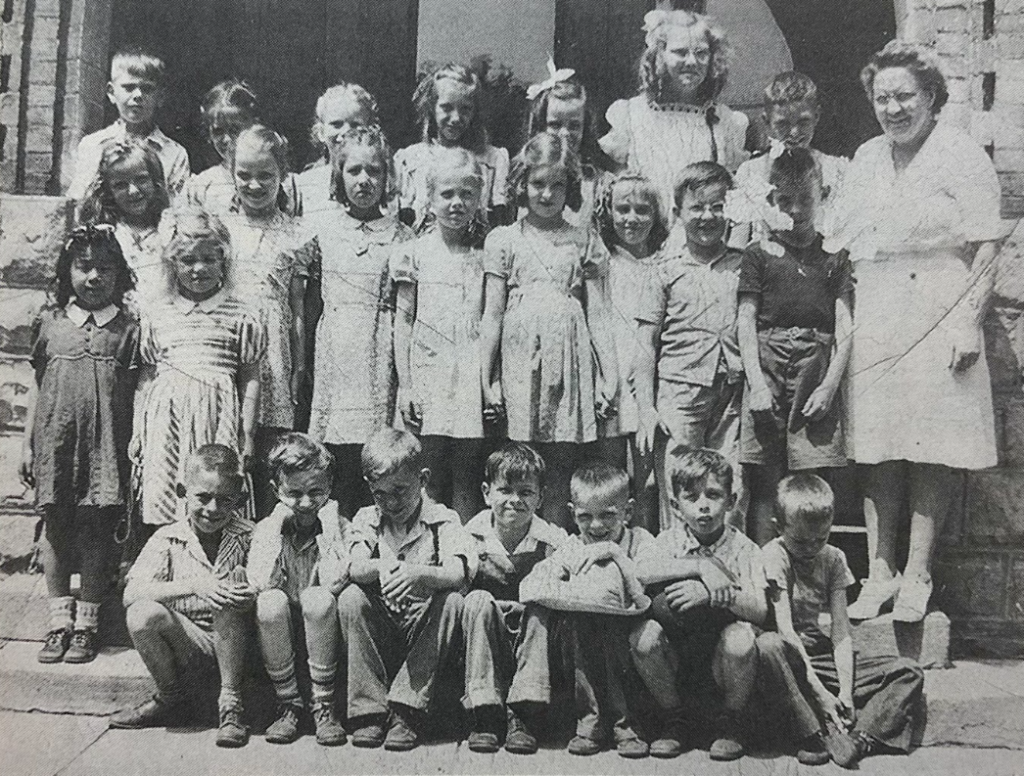

Courtesy of David Palmer

Mary Wong (far left) in Ms. McKinley’s first grade class at Royce School in 1943.

“Throughout my entire life, I have been supported by my older brothers and sisters.” Mary said. “With any challenge, disappointment or problem, someone would always be there for me. And, because I followed six siblings who were excellent students, active participants and leaders successful in school and in the community, they made my path to adulthood easier.”

Because of their well-known restaurant and the reputation of Mary’s older siblings as excellent students and leaders, Mary said she experienced less racism from their neighbors. She said that many of her friends, all Caucasians, were children of immigrants from Europe and accepted her totally, never mentioning her ethnic origin. Even so, she was warned about the racial tensions that were exacerbated during World War II.

“I was most aware of my race and ethnicity during WWII, when kids would call me a ‘Jap’ or the enemy,” Mary said. “Beginning when I went to school my mother would tell me to say I was Chinese, not Japanese.”

She never realized why Yee Shee stressed that differentiation until decades later, when she was married and living with two children in Berkeley, California: After moving to the state in the 1970s, Mary had learned that one of her best friends, a Japanese American woman, was relocated to a camp during the war as part of a larger movement where the U.S., in fear that citizens of Japanese ancestry would act as spies, forcibly relocated and incarcerated them along the Pacific Coast. The woman’s parents had “lost everything,” and her three younger brothers’ education was severely compromised as a result of the relocation.

Her actions in communicating with the rest of her family to record the history of Yee Shee’s influences have allowed for the Wong family values to be passed down and maintained, namely through the triennial Wong family reunions.

These reunions have taken place across the West Coast and Midwest, from Seattle and Beloit to Salt Lake City. Several second-generation family members took the lead in planning all the generational events until 2022, at which time third-generation family members assumed the responsibility. The reunions hold entire-family and individual family dinners for smaller gatherings to get acquainted.

At the reunions, dozens of family members celebrate their history. Their latest reunion, in the summer of 2022, involved a panel with three surviving members of the second generation, who answered questions about their experiences growing up in Beloit.

Besides carrying on family traditions through these reunions and storytelling traditions, Hannah said her grandmother’s emphasis on family has translated into her own values and experiences.

While Hannah feels that she didn’t have a grasp of the significance of her great-grandparents’ immigration to the U.S. when she was younger, she said she’s now more aware of how meaningful and courageous their move was. After absorbing more stories about the assimilation and the experience of growing up Chinese American from her grandma, she also recognized the importance of keeping her great-grandparents’ legacy alive through the generations by maintaining them herself.

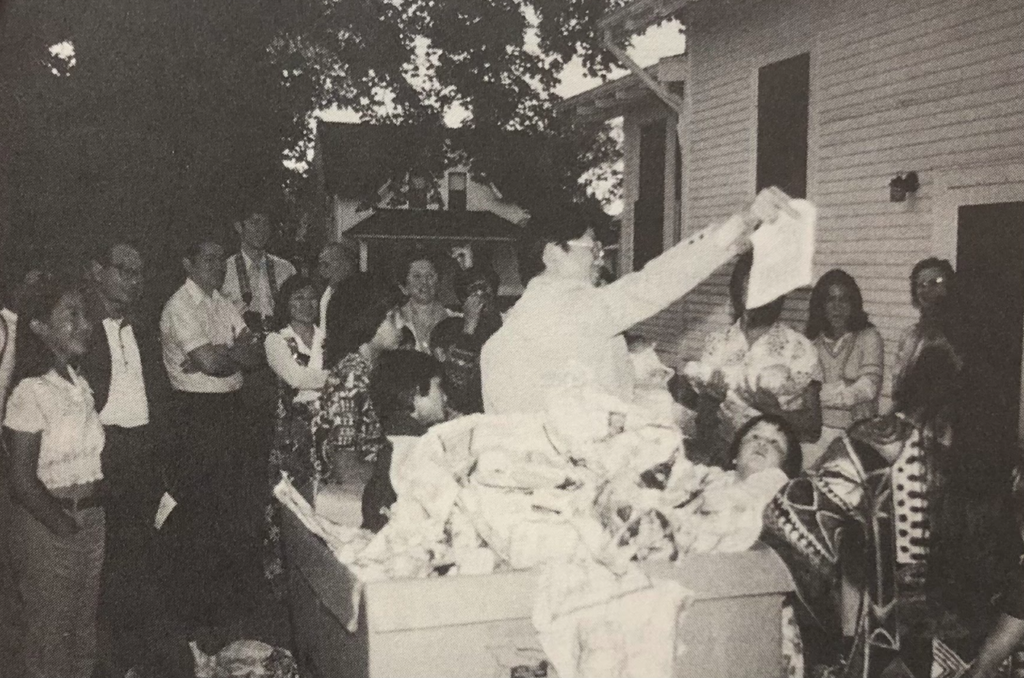

Courtesy of Lisa Fortsch

Frank Wong, Mary’s brother, pops out of a box during the 1982 Wong family reunion.

“I can recognize that my own family has had more generations since immigration, and that makes my approach to the concept of immigration — especially being a white American—much less shaped by personal experience,” Hannah said. “While I can never understand the experience of being a first-generation immigrant-American, I hope that I can continue to be mindful of these differences and the ways in which my own life has been shaped by earlier immigration within my family.”