Senior Grace Li describes the process of shooting a bow as a methodical, mind-consuming task. Unlike the simple draw-nock-shoot mechanism portrayed in movies, shooting Li’s 6-foot bow is an 11-step process, which starts long before she steps up to shoot.

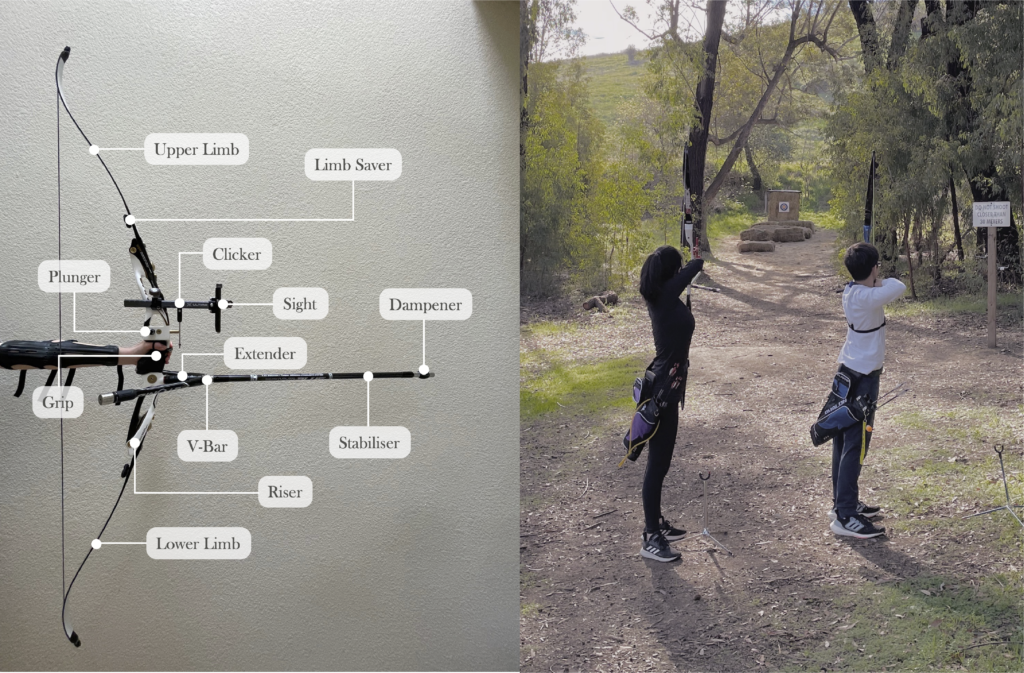

She must carefully tune her instruments, such as her scope and clicker,and maintain a consistent draw-length, the amount she is able to pull on the string. Afterwards, she must make sure to fire at the proper angle (in her case, adjusting a double-jointed elbow so that it isn’t grazed by the string), and follow through with her shot properly.

In this complex setup and methodical process, Li has found herself gaining not only physical, but mental strength from the sophistication required for a successful shot.

“I’ve come to enjoy not only the physical challenge, but also the mental aspect of archery,” Li said. “As our club director likes to say, archery is ‘fifty percent physical and fifty percent mental.’”

Li joined the sport when she was 13, and her efforts haven’t always been successful. At the Cub (13-15 years old) division of the 51st California Nationals, Li vividly remembers bursting into tears from the pressure. Halfway through the competition, she completely missed the target, while the girl next to her was scoring 9’s and 10’s, with 10 being the highest point possible.

“Your mind becomes your worst enemy,” Li said. “You’re seeing your teammates and other people next to you, and you’re seeing how well they’re shooting. And I always ask myself, ‘What am I doing wrong?’”

Since then, Li has improved markedly and credits the camaraderie and time spent with teammates at her club. She now looks back at the whole situation with amusement.

“The pressure seemed overwhelming at the time, but in hindsight, I think it was rather hilarious,” Li said. “Later, I discovered that the girl I was next to was No. 1 in our division, which made me feel a bit better about our gap in ability. She was very kind and encouraging to me and even congratulated me when I finally shot a 10.”

In archery, divisions and competitions are named by the type of the bow used and the age of archers. Li, who shoots with the Recurve bow — the most common type and the one used at the Olympics — has been competing in the 15- to 17-year-old division. Standing 18 meters from the 40-centimeter wide target, Li is allotted 2 minutes to shoot three arrows in an “end,” or round, and shoots 20 ends over a two-day competition.

Li practices at the Los Altos Hills Archery Club (LAHAC) on Saturdays for indoor training and occasionally goes to the Black Mountain Bowmen Archery Range in San Jose for outdoor practice on Sundays. Her flexible schedule allows her to practice often — from three hours on weekdays to all day on weekends.

Since joining the club in 2019, she has participated in three competitions; however, she is not ranked because players who are ranked must participate in a minimum of three competitions a year.

Courtesy of Grace Li

Left: A breakdown of Li’s recurve bow. Right: Li and a fellow archer practice during the outdoor season at Black Mountain Bowmen Archery Range in San Jose.

Her team also bonds through weekly mini-competitions. The archer who scores the lowest every weekend must endure a “punishment,” usually a set number of pushups (following the formula [highest score] – [lowest score], all divided by two) or planks (the number of pushups times 10). Once, after coming back from winter break this January, Li had to hold the plank position for 210 seconds, and her teammates didn’t let her leave until she finished.

Once Li turned 15, she was allowed to take a written and practical exam to obtain a Level 1 Coaches License, which allowed her to become an official “teacher” and correct her teammates on their stance.

She also works with a subdivision at her club called the Special Needs Activity Clubhouse, in which players like Li coach neurodivergent archers by helping their stance or providing emotional support.

“Coaching neurodivergent archers is what made our club less competitive and more community oriented,” Li said. “In many other clubs, archers start early and go every day to train because they want competition results. But in our club, there’s a larger aspect of community and volunteering.”

Though Li loves archery, she called it “monotonous,” needing a “perfect repetition” of a good shooting stance in order to accurately hit the target each time. Sometimes, while she may understand the mechanics behind a certain stance, she has trouble replicating it.

“My mind comprehends how to replicate the form; I know in my head what I need to do, but my body just can’t replicate it,” she said. “It’s really frustrating because my body just won’t listen to my mind.”

For example, she often forgets that she shouldn’t grip on tighter to the bow after she shoots her arrow — which she instinctively does — as it messes with the flight of the arrow. Instead, she needs to let the bow drop and be caught by her finger sling.

These hard standards have in fact allowed Li to gain a better handle on the mental aspect of archery.

“This sounds counterintuitive, but actually, I found that the less you care about your shot, the better you perform,” Li said. “As soon as the pressure came off, I started performing a lot better.”

In turn, she has learned to overcome the crippling pressure she experienced at her first tournament.

“Now, I can take peer pressure and turn it into motivation,” Li said. “So whenever I see other people doing better than me now — even in academics — it motivates me to work harder and improve so I can be on their same level. That’s what I love about archery.”