It is not uncommon to see upperclassmen with only AP and honor classes in their schedule. Sadly, to handle that extreme load, some students resort to cheating.

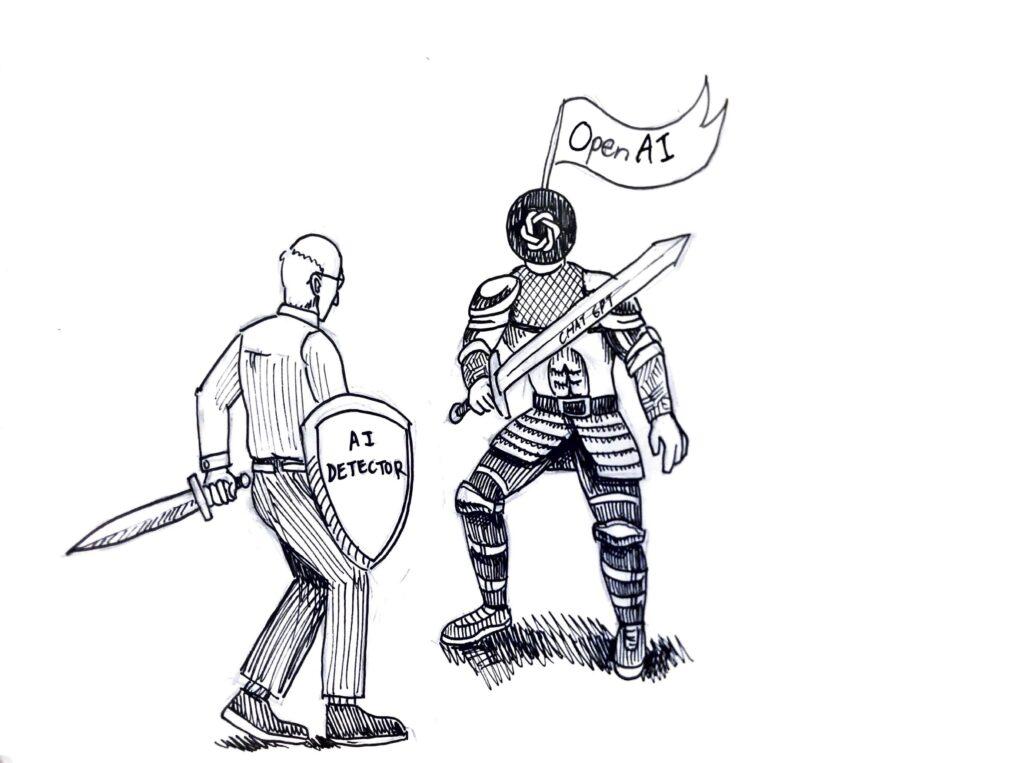

And the problem and temptation of cheating has suddenly gotten worse thanks to ChatGPT.

Recently, 53 students were caught using ChatGPT to cheat on a series of four AP U.S. History (APUSH) review assignments.

These students were flagged by ChatGPT detectors, which are notoriously inaccurate and produce many false positives. After an investigation, administrators determined that 28 out of 53 students had used ChatGPT to do the assignment and were punished. Suddenly, teachers and administrators are scrambling to figure out what to do to stop what may be a wave of potential AI-assisted cheating.

ChatGPT usurps the learning of basic critical thinking and argumentation skills in students, so to minimize its use, classes must place more emphasis on in-class assessments or projects while making careful completion of homework and classwork necessary to do well on said assessments and projects.

Students still need to know how to write essays

Some argue that if ChatGPT is able to complete a regular homework assignment, then that assignment is not worth the student’s time. They expect teachers to challenge students’ creativity in every assignment with projects. The idea is that AI is not creative, so it wouldn’t be possible to use it for such assignments.

This interpretation is weak for several reasons.

First, making every assignment a project is unrealistic. And even if students work in groups, few would want to constantly do so, not to mention the frustration among students about the work split between members.

Moreover, projects do not necessarily cover all the important skills to learn. Not all projects force students to think critically, an aspect that’s directly challenged with, say, analytical essays about literature. While writing literary analysis essays is not relevant to many jobs and might be duplicated by AI, these kinds of open-ended writing assignments strengthen students’ ability to think critically and create cohesive, persuasive arguments and formulate original insights, skills that are vital beyond school assignments.

The fundamental reason behind cheating is simple: preoccupation with grades. Too often do students walk up to teachers holding an assignment, arguing for a grade they felt they should’ve gotten.

And unfortunately, some students view AI as the perfect tool to achieve ideal grades due to its accessibility and subtlety compared to plagiarism or copying off friends’ work. The current lack of regulation of ChatGPT allows for a tempting way to cheat, evidenced by the APUSH incident.

Even if it is possible to cheat your way through high school, doing so would also cheat yourself of the critical decision-making skills necessary for real-life leadership. Allowing AI to make judgments at the high-school level doesn’t teach fundamental decision-making skills that are required beyond the walls of high school.

School is for learning, and policies should encourage this

The prevention of cheating comes in two forms: deterrence and incentive.

Deterrence means making the risk of cheating outweigh the potential reward, and it is simple enough for in-class assignments. In the worst-case scenario, humanities teachers can just make all assignments of the pencil and paper variety, which is already the case in most STEM classes.

However, it is more difficult to regulate ChatGPT use in homework assignments. Even if pencil and paper submissions were required, students could just manually copy ChatGPT responses onto paper.

The current methods the school has to regulate cheating via ChatGPT — AI detectors and meeting with teachers or administrators — are arduous and impractical for the rate at which incidents are likely to happen.

The week-long investigation into the APUSH cheating incident makes clear that trying to prevent students from using ChatGPT by threatening punishment is ineffective and only drains the school’s resources.

So how could the school lessen cheating through AI? This is where incentive comes in: Students should have a real reason, outside of just the grade, to do homework and classwork. Scoring high on assessments is the ultimate proof of proficiency in course content, so by changing grade weighting in classes like APUSH and English 11 Honors to favor assessment grades, consistent with other AP classes like AP Calculus BC and AP Physics 1 and 2, students would be incentivized to use homework and classwork to fully digest concepts and score well on assessments, projects and essays.

This policy might be highly unpopular with students who depend on classwork and homework grades to boost their grade. However, the fact that most students are not getting A’s on tests or essays and still feel entitled to an overall A grade sends a concerning message about the school’s academic culture and students’ mindset.

While the school may not be able to combat all AI-assisted cheating, these policies of deterrence and incentive can ensure students actually learn from these classes. And, as an added benefit, these policies might also help discourage students from taking more APs and honors classes than they can handle.