Growing up in the early ‘80s, a young Brad Ward lived in a world where being transgender or gender-divergent were concepts unknown to the majority of society. Almost 50 years later, after finding a career in college admissions, moving to California from Pennsylvania, battling supervisors who she perceived as trying to muffle her voice when she came out as a transgender woman and finally joining the SHS community as the school’s college and career counselor earlier this school year, Ward is on her way to living the life she wants.

She is solidifying her gender identity as a transgender woman through gender-affirming care while working at SHS, where she said she feels financially and emotionally supported enough to undergo the physical aspects of gender transition. SHS was also the best place for her to publicize her transition and serve as a role model to gender nonconforming students, Ward said. (While she identifies as female, she has so far retained the name Brad.)

“I was the only transgender college counselor in this whole country until a month ago, as far as I know, and I need the national visibility that a district like Saratoga can provide for people like me,” she said.

Though she has encountered cases of blatant transphobia throughout her journey of self-discovery, Ward remains proud of her identity. She hopes to serve as a reminder that all transgender people, just like everyone else, can flourish in any corporate or educational community.

A childhood discovery of her identity in a religious, conservative society

Born to conservative parents in Ohio and growing up in Marin County, California, Ward attended Mass weekly and was enrolled in Catholic schools throughout her childhood, a time in her life when she began to feel “different.”

During her time in private high school, she had to wear gendered uniforms and grappled with her confusion by hanging out with girls and joining cross country and track, the only co-ed sports offered, because she did not feel like she fit in with the boys at her school.

“I should be wearing skirts, not pants,” said Ward, describing her thinking as a teen. “Why do I want to hang out with the girls more than the boys, wear skirts and stereotypical [female] things like that?”

Without knowledge of gender science beyond the binary genders assigned at birth, society labeled transgender people as “transsexual” or “crossdressers,” which were derogatory, pathologically connotated terms, she said.

The AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) epidemic of the ‘80 and ‘90s fueled false associations between HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and homosexuality, making it even more challenging for Ward to understand her identity.

“I basically figured that I must be gay, because back then, if you were like an effeminate boy or an effeminate man [a male who displays female characteristics], people just assumed you were gay,” Ward said. “But why then why was I attracted to women? It just didn’t make sense.”

While she attended college at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania, Ward found no official transgender community or mentors to confide in. However, attending a non-religious school allowed her to detach from the misogyny she observed in the many male religious figures of her youth.

Finding a transgender role model

After graduating from Bucknell in 1990, Ward worked in sales for international shipping and greeting card companies. Many of her clients were colleges; naturally, she visited many of them, from the Midwest to the East Coast.

“I would be on a college campus and just knew that I was supposed to be there,” Ward said. “I just didn’t quite know how yet.”

Everything changed after she was offered a job in college admissions at Bucknell in 2000 at her 10-year reunion. A few years later, a colleague introduced Ward to the book “She’s Not There” by Jennifer Finney Boylan. In the book, Boylan, a professor at Colby College in rural Maine, detailed her experience coming out and undergoing gender-affirming surgery and care (medical procedures that allow transgender people to physically transition their body to align with their gender identity).

“I read it all in one afternoon and I thought, ‘Oh, my god, there’s so many like me out there.’ It was the first time that I felt like I wasn’t alone,” she said. “If Boylan could be accepted after having sex-reassignment surgery and hormone therapy in a place as conservative as rural Maine, then so could I.”

Ward started trying on female clothing — just like Boylan, she experimented with wearing skirts and female-gendered clothing on Bucknell’s campus, college fairs, high school visits and more. But it wasn’t a smooth path, and she ended up having doubts and even getting rid of the clothes.

Facing obstacles at Menlo High School and coming out to inspire LGBTQ+ youth

By 2007, Ward was working at Menlo, a private high school in Atherton; she began experimenting with more easily reversible changes such as growing her hair out and experimenting with clothing.

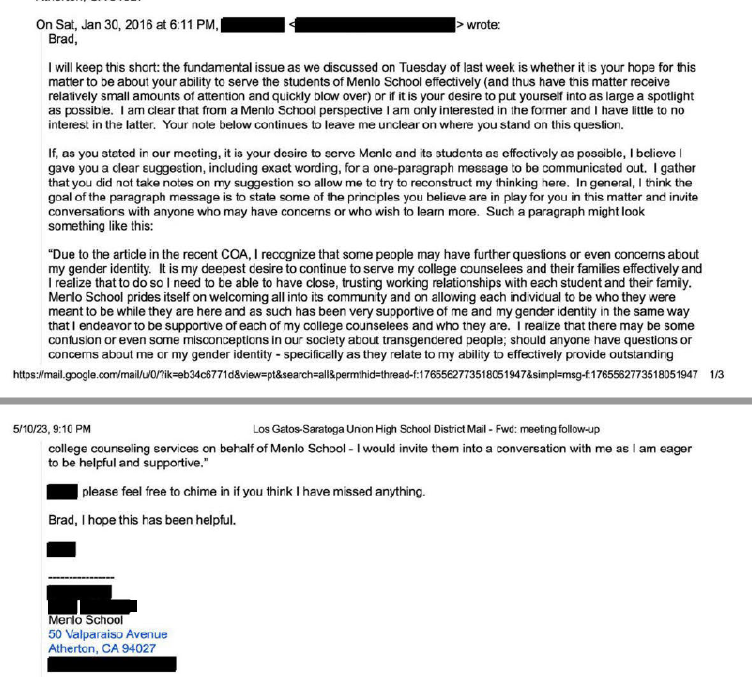

However, two years later, two of her direct supervisors began expressing concerns for her “feminine” appearance. She said two of her direct supervisors asked her to cut her hair.

“Unfortunately, I had only been at that school for two years, and as a trans person who was still closeted, there were very few of us out there,” Ward said. “There wasn’t really anything I could do but lay low, cut my hair, be quiet and let it go.”

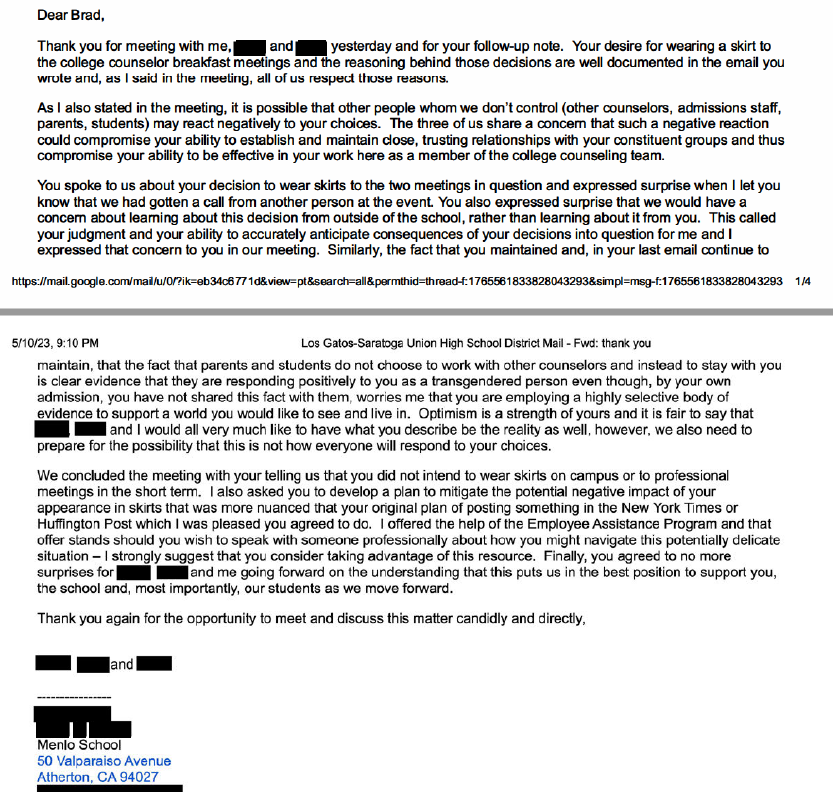

Several months later, before her hair had even grown to reach its previous length, the same supervisor asked her to cut it once more. Six years later, one of the previous supervisors and two additional ones continuously reprimanded her choices of self-expression. Following a string of 10 suicides by trans teenagers across the country — one of whom was Ward’s brother’s former neighbor —Ward became determined to combat the transgender stigma by wearing a skirt at two public, off-campus college programs. Someone at one of the meetings reported her to Menlo, and she was called into a meeting, only to be warned against “negative impacts of her wearing skirts on campus” in a later email. When she raised the idea of finally coming out publicly and recounting her transgender story in a national news platform such as the New York Times, the supervisors shut her down immediately.

Each time, out of fear of losing her job and prioritizing her parents’ declining health over the issue, Ward complied with her supervisors’ wishes.

“At the end of the meeting, it was three of the most powerful supervisors at Menlo, against a transgender person. So I thought, ‘I guess I won’t wear skirts in the short term; why would I, after getting called into a meeting about it?’”

Nevertheless, over that summer, Ward began experimenting with clothing again in her free time without the additional pushback from the school. One of her favorite pastimes was hiking in skirts, saying, “The whole world was totally fine with it.”

With the tail-end of liberating summer and the welcoming diversity meeting on the first day of the 2015-2016 school year, Ward felt empowered to come out as transgender to the nearly 90 staff and faculty at that same meeting. She was met with raucous applause from colleagues.

While she initially felt empowered to address the issue of coming out in her personal blog, Ward was shocked to receive a request from the supervisor to reduce the lengthy description of her experience down to one disappointing paragraph. Furthermore, in her draft, Ward had copied five other administrators whom she felt supported by. But in their response, her three supervisors cut those five administrators out, isolating her from her chosen allies. In the end, only one of the five replied to her separately — the Director of Diversity.

By cutting her off from her chosen allies and restricting her voice and gender-identity expression, Ward thought Menlo’s administrators’ actions during her employment there were a violation of federal law against sexual harassment, sexism, discrimination, anti-trans and an abuse of power.

But instead of taking legal action, she published her coming-out piece to her own personal blog. She was fed up with trying to compromise on her own identity and losing control over her self-expression. In the following school year, both her parents’ health deteriorated — her mom was placed into assisted living and her dad was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She spent the rest of the year preoccupied with driving back and forth from Atherton to Los Angeles — where her parents were located — and her conflict with the three supervisors came to a temporary halt.

She was eventually let go from Menlo in 2017 because of her being “unable to effectively work with students and colleagues.” Shortly after, she began interviewing for new positions with the pronouns “she/her/hers,” wearing skirts and clearly displaying her gender identity.

Finding a community accepting of her identity

When Ward arrived at SHS last August after working at Silicon Valley International High School, Menlo-Atherton (different from Menlo), Terra Linda and South San Francisco, she said she found the sense of community that she needed to confidently begin her permanent physical transition. Last spring, she reached out to health professionals to start her treatment and found clinicians specializing in gender-affirming care who helped her feel comfortable and accepted.

On Sept. 26, 2022, Ward deliberately took her first gender-affirming healthcare supplements at a college conference in one of the most anti-transgender states in the nation — Texas, which has introduced more than 10% of all state-level legislation in the U.S. restricting transgender expression, access to gender-affirming care and more. There, she took her first testosterone blocker (a pill that blocks the male hormone, testosterone) and estrogen patch (a patch that sends the female hormone estradiol into the bloodstream to produce feminine features).

“I thought starting my process [in a state] where things were so wrong was symbolic and something I needed to do there, instead of being surrounded by a lot of peers and colleagues at the conference,” she said.

Since then, she has continued taking testosterone blocker pills twice a day and replacing her estrogen patches twice a week and is waiting for it to finish in September so she can assess when she can pursue gender-confirmation surgery.

Thanks to the medical insurance that the district provides to its employees, Ward is able to afford taking testosterone blocker pills twice a day and replacing her estrogen patches twice a week. Without the insurance, doctor visits for her would cost upwards of $900 by the hour, while both the pills and patches would have already amounted to thousands since she started treatment nine months ago.

Ward has never regretted her decision to start hormonal therapy — she has already seen the physical changes appearing: Her unwelcome facial hair has nearly disappeared, her skin has become softer, she is developing breasts and hips and she puts on weight much easier.

“All the years that I would look at myself in the mirror and be like: ‘No, it’s not really you.’ I mean, they call it gender-affirming care for a reason,” she said. “I’m not sure when it disappeared, but that overwhelming doubt about who I am is gone now.”

Even though she is happy with her progress so far, had she been given the opportunity to use pubertal suppressants as an adolescent, Ward believes that she would have undoubtedly done so. Without knowing enough about being transgender and having access to hormone therapy in her childhood, Ward believes that transgender minors should have the choice to pursue gender-affirming care, regardless of their age.

From her beginnings in a strictly Catholic environment, to finding and fighting for an accepting community in the workplace, Ward has stayed true to her identity. She hopes to be the model of transgender success that she sorely missed during her own childhood — and to students at SHS who identify as transgender, nonbinary, gender-divergent, etc., Ward has three words: “Hang in there.”