In 2018, court documents filed in the case Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard alleged that Harvard University officials lowered their internal personality scores for Asian American applicants in an effort to reduce Asian American enrollment in its undergraduate class. The court case, filed in an attempt to combat race-based affirmative action, will be decided by the Supreme Court later this year, perhaps reversing decades of precedent.

Canonical opposition of affirmative action points to unfair practices like those of Harvard aiming to show the so-called “positive discrimination” actually leads to unnecessary inequity against qualified applicants. Other arguments claim that the problems affirmative action tackles can be solved more effectively by boosting socioeconomically disadvantaged students instead.

But this stance misses the true goal of affirmative action for elite schools like Harvard: Not to form a truly holistic and ultimately meritocratic system where the most deserving gain admission, but rather to produce a carefully calibrated student body to uphold their public image and money-making business.

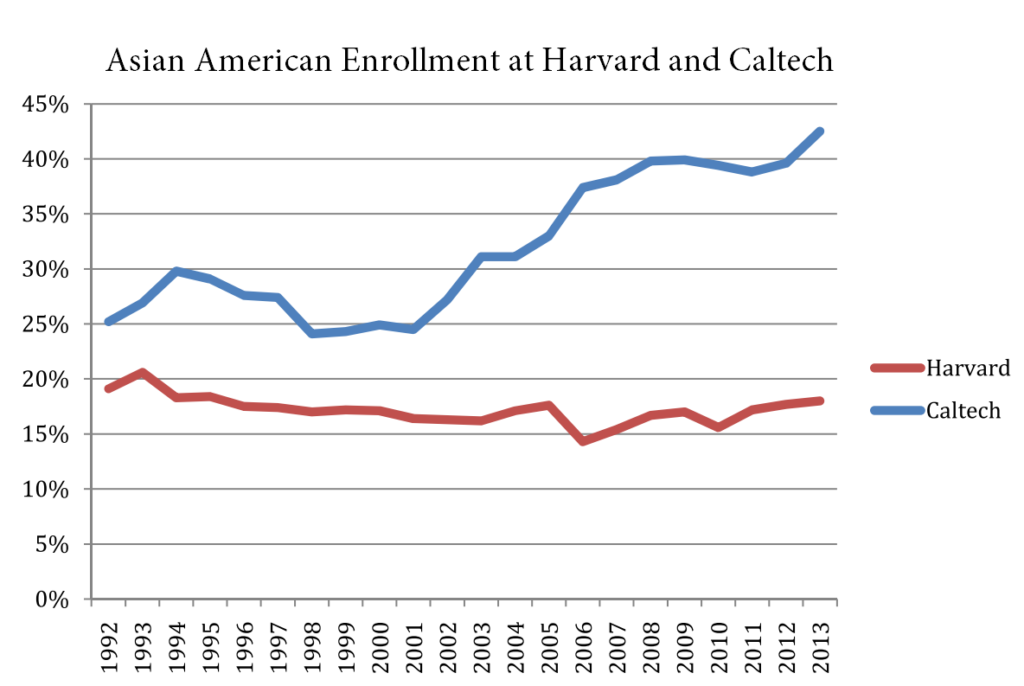

For example, the original complaint by SFFA points to differences in Asian American enrollment between Harvard, which takes race into account in admissions, and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), which does not. Harvard’s percentage of Asian American enrollment stayed flat, while Caltech’s dramatically increased between 2000 and 2010, purportedly proving that Harvard’s use of race-based affirmative action causes it to deviate from the (implied) “ideal,” in which students are selected based on academic merit alone.

Regardless of whether these differences positively or negatively reflect on Harvard’s admissions process, they demonstrate that Harvard takes extreme care to have a precise racial makeup for its class, in contrast to Caltech. So do Harvard and its admissions officers truly believe that its system of “positive discrimination” makes Harvard a better place to study? Maybe. But ultimately it does not matter because Harvard believes that delicately balancing its undergraduate class and advertising itself as a bastion of “diversity and inclusion” help secure its place as an elite Ivy League institution.

In a similar way, Harvard has come under fire for its practice of legacy admissions, in which the relatives of alumni, especially well-heeled donors, are more likely to be accepted. The original complaint by SFFA alleges that Harvard uses a special admissions list called the “Z-list,” from which around 20 to 50 students are selected each year, to admit overwhelmingly white, legacy, wealthy and academically worse applicants.

However, regardless of whether Harvard actually cares to help those who are less fortunate by giving them financial need-based admissions boosts, rewarding the alumni who donate to Harvard actively encourages other wealthy individuals to give money as well.

As a result, Harvard’s actions say that the school is willing to admit a few dozen less deserving individuals if it means that they will continue to receive large donations. In other words, Harvard puts its success as a business above other factors.

Thus, arguments, like those in the Supreme Court case, that treat affirmative action as a purely ethical issue on the best way to combat the past abuses of discrimination ignore the root cause of the issue: The fact that schools like Harvard are incentivized to make a profit.

Actually “fixing” affirmative action, then, requires a dramatic shift in how private colleges are viewed, away from selling a certain education (and its corresponding degree) for a price and toward preparing all people for the world. But this is a cultural rather than a legal shift — perspectives must change before laws can. Before then, attempts to fix the consequences rather than the causes of affirmative action, even those handed down by the Supreme Court, will be much ado about nothing.