I’m no sports fan. If you ask me which team I support in the Olympics, I don’t usually have an opinion, dissociated by my lack of knowledge and the added complication of being a Chinese-American immigrant.

However, there is one team I fiercely rally behind — and that is the China women’s national volleyball team.

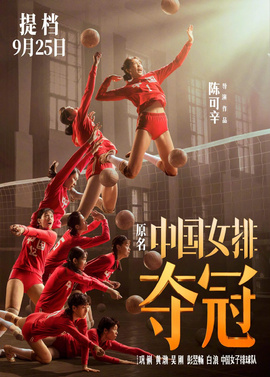

In September 2020, I awaited and watched the biographical film “Leap”(”Duo Guan”) that details three decades of the team’s history, with its current players portrayed by their real-world selves. Although the film was trapped by its dual purpose as government propaganda, the very real stories and people in it shine too brilliantly to be tainted.

I’m not a fan of sports, but a fan of the team’s values that fuel my pride for my heritage.

The Iron Hammer

Critics say that “Leap” is better titled “Biography of Lang Ping” for its central figure, portrayed by renowned actress Gong Li. Lang, nicknamed the Iron Hammer for her prowess as an outside hitter, is pivotal to the film and defines its three stages.

In the first, the team grapples with the disadvantages of a society left in tatters by the Cultural Revolution. A young Lang, portrayed by her real-life daughter and former Stanford volleyball player Lydia Bai, joins China’s team in 1978 and plays a central role in its five consecutive world championships through back-breaking training.

In the second, a retired Lang coaches the U.S. women’s national volleyball team and leads it to defeat the Chinese team at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, marking the period when China’s socio-economic advancements have rendered finding pride through athletics obsolete.

In the third, Lang returns to the Chinese team as a coach, bringing innovative techniques in recruitment, coaching and substitutions that eventually succeeded in creating today’s team that boasts players like captain and outside hitter Zhu Ting, one of the best volleyball players of all time. After a trying quarterfinals in which they defeated the host Brazil, the team seizes gold at the 2016 Rio Olympics as the first of its many more victories.

Neither here nor there

Lang is a cultural icon to the Chinese people, but her 15 plus years of residence in the U.S. creates tensions I know too well.

“Leap” adopts a non-linear structure that opens with the team’s lowest point during the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when the Chinese team — coached by Lang’s former assistant coach and friend of 30 years, Chen Zhonghe — loses to the U.S. team Lang coaches.

It is also a poignant point in Lang’s career. Lang sits expressionless as her team scores the winning point and erupts in cheers. She walks out with brisk strides, the spectators’ inaudible shouts of “traitor!” — judging by the slow-motion movements of their mouths — flooding the stadium in a deafening silence.

What was Lang supposed to do when her professional responsibility was pitted against her former team, her youth and her greatest pride?

When the film premiered in September 2020, China was experiencing heightened nationalistic sentiments and America intense waves of anti-Asian hate following the COVID-19 pandemic. As a daughter of the two countries, my feeling of belonging in both shattered into neither.

Perhaps holding our heads high, unashamed of our love for both, is what Chinese-Americans can do in such times.

“Leak blood yet never leak tears; break skin yet never break team”

Much more elegant in Chinese than I can translate, the subtitular slogan that appeared on one of the promotional posters lies at the core of the team’s first stage.

China was severely behind economically in the 1980s, resulting in underfunded teams with inadequate facilities. In one memorable scene, Lang’s head coach Yuan Weimin learns that foreign teams are using computers to strategize and inquires whether the Chinese team can obtain one. A techie tells him that China has a single computer, larger than a truck and understood only by a few — of course it cannot be used for sports.

The coach’s response was resolute: He raises the net by 15 centimeters and spikes merciless hits until a player breaks into tears. He stares into the techie’s eyes and asks, “So we train like this. Can a computer calculate this?”

What the team lacks in technology, it makes up with sweat and unyielding drive. Thus begins a grueling training regime in which players scream themselves hoarse as they throw their bodies again and again onto the hard court to pass balls, blood staining their knee pads.

“We can’t compete with others’ training conditions, so we can only throw down our lives,” the coach said.

What’s more, the team has the nation’s unsullied support. In those simple times, crowds gathered in front of treasured black-and-white television to cheer for the team as they defeated Japan at the 1981 International Federation of Volleyball World Cup.

The team’s journey of overcoming dire circumstances with the sheer tenacity of human will is one I hold dear. I remember playing for my Chinese elementary school’s volleyball team in fifth grade, forearms littered with bruises from the coach’s hard spikes and practicing with a basketball against the wall. The goal was 100 consecutive passes, then 200, and then 300, before I lost track of my record.

Today, I know the ability to pass continuously with a wall is fairly useless in a game, and I’m nowhere near a good volleyball player because the sport itself was never the point for me. Rather, the lessons I learned in conquering pain now drive me to achieve other things I want to excel at, and I’d say I’ve done pretty well for myself.

Cultural Confidence

My experiences pale before the hard work of generations of Chinese people striving to rise from outdated beliefs and rural backgrounds. China has grown so much in the past three decades as symbolized by its women’s volleyball team — and that should be the heart of the government’s popular slogan “Cultural Confidence.”

However, the government has twisted these innocuous words for hyper-nationalistic purposes, waging campaigns to eradicate English-language education and non-Lunar holidays. It breeds a society in which foreign nationals are scorned and Chinese nationals ridiculed for the slimmest connection to other countries. It breeds the necessity for me to remain anonymous in this article.

Just as I applaud America’s rough but relentless journey toward celebrating diversity, I hope China can also love other cultures for their differences. Cultural Confidence should be achieved in highlighting how our stories, such as the one of the women’s volleyball team, are brilliant enough to shine on their own. Cultural Confidence does not call for suppressing other cultures.

“Leap” is among the plethora of Chinese movies that idealize the country and its ruling party. It cannot escape its associations as propaganda. But the team’s story is also laden with the people’s untainted aspirations that shapes China into the hegemony it is today.

Although exploited, the team’s values cannot be diminished. We feel it as pounding hearts and rushing blood — a blood associated with a China that I’m both critical and fiercely proud of.