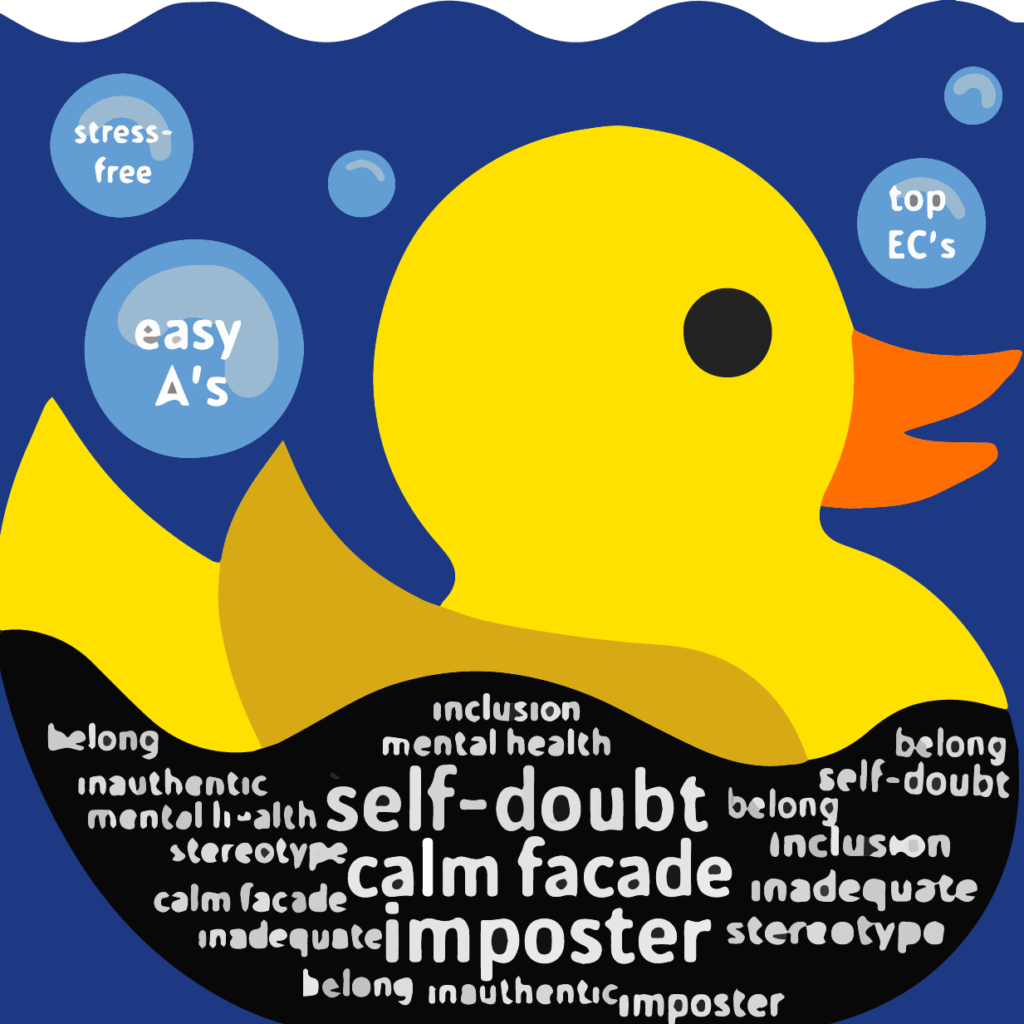

In a highly competitive school like Saratoga High — which ranks as the No. 1 best college prep public high school in California according to Niche — students uphold a reputation of high grades, impressive extracurriculars and polished résumes. But underneath this seemingly flawless exterior, many struggle with an academic pressure cooker culture that fuels “duck syndrome.”

Duck syndrome describes the phenomenon in which students put up a calm facade, seemingly floating peacefully along the surface of the water; at the same time, they hide their internal feelings of distress or self-doubt, paddling frantically underwater as they struggle to stay afloat.

A similar syndrome is “imposter syndrome”: feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt that persist despite evident success. Imposter syndrome disproportionately affects high-achieving individuals who find it difficult to accept their accomplishments and status.

To learn more about duck syndrome and related syndromes, The Falcon interviewed Geoffrey Cohen, a Stanford Professor of Psychology in the Graduate School of Education, who has conducted research on the threats of losing a sense of belonging and self and its implications for social problems. He has found that conditions of self-doubt concerning one’s belonging in groups have become especially prevalent in recent years.

“The defining feature of our era seems to be that few groups feel confident in their belonging,” Cohen said. “Feelings of inadequacy such as duck syndrome and impostor syndrome are manifestations of conditions where people feel that they have to present an inauthentic self to feel like they belong.”

Cohen added that the lack of discussion regarding duck syndrome contributes to its toxicity. This leads to a “double-whammy effect” known as pluralistic ignorance, in which individuals feel that they are uniquely miserable because nobody shares their struggles.

“I think people don’t understand that if you hang in there, talk to people and make connections, eventually you [overcome duck syndrome]. That’s the kind of wisdom that’s wasted on the older generation,” Cohen said.

From an evolutionary perspective, Cohen said that humans are a social species who have evolved to go through life together and are “exquisitely attuned to threats to our inclusion in our group.”

As such, he emphasizes the importance of belonging and community. Lack of connections has grave implications that worsen as people grow older.

Social isolation and loneliness are associated with a 50% increased risk of dementia, 29% increased risk of heart disease, 32% increased risk of stroke and higher rates of depression, anxiety and suicide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additionally, research by the National Institute on Aging shows that for adults aged 50 and older, feeling lonely — a counterpoint to belonging — is as toxic for physical health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

“It’s a distressing state of mind to be in,” Cohen said. “It’s bad for our health. It’s bad for our psychology. It’s bad for our persistence and intrinsic motivation; it’s really hard to be motivated and passionate about something when you constantly feel under threat of not fitting in.”

Causes of duck syndrome

Cohen said periods of transition from one life space to another, such as from high school to college or college to profession, are often when people are most vulnerable to experiencing duck syndrome, a pattern he attributes to the lack of strong social bonds when attempting to integrate into new environments.

Describing this period of transition, Cohen referenced an interview on the art of storytelling with Ira Glass, host and producer of the radio and television series “This American Life,” in which Glass discussed “the gap” between where a person is and where they want to be. Applying the gap concept, Cohen said duck syndrome is especially prevalent during the beginning of transitions into new competitive environments like selective colleges. In these situations, students are trying to learn challenging new concepts and often see how much they’re falling short compared to their peers.

In their 2007 research paper “A Question of Belonging: Race, Social Fit, and Achievement,” Cohen and Stanford Associate Professor of Psychology Greg Walton coined the term “belonging uncertainty,” a state in which susceptible groups are more sensitive to feeling as if they don’t belong in a given community.

Their study suggested that in academic and professional settings, groups coming from socially stigmatized, negatively stereotyped, marginalized or underrepresented groups are more prone to belonging uncertainty, as they often experience subtle acts of bias or microaggressions that may hinder their sense of belonging. This results in less challenge seeking and less motivation following adversity, as well as poorer health and wellbeing.

Additionally, citing Susan Cain’s “Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking,” Cohen said people who are introverted may also be more prone to duck syndrome, as they are forced to be vulnerable and public during activities like large social events at workplaces where they are pushed out of their comfort zones and struggle internally.

Ways to cope

To mitigate the effects of these issues felt by so many young people, Cohen suggests a few simple interventions.

He said creating support groups and safe spaces to share stories with others who are quietly struggling against adversity can be a powerful remedy.

“Take a risk and express your own vulnerability. Of course, you have to be careful: I do feel like sometimes if you’re vulnerable, you can be shot down,” Cohen said. “But if you’re in a safe space with people that you trust, sharing those struggles and even strategies for overcoming them is going to be very helpful.”

Cohen related one of his own struggles with belonging uncertainty to illustrate his point. He said one of his worst experiences of belonging uncertainty was when he was going into his first year as an assistant professor at Yale University. Despite attending selective schools like Cornell University for his undergraduate education and Stanford for his graduate studies, he had self-doubts about his teaching career.

“I had been pretty confident in my abilities, yet nevertheless, stepping onto this campus, I was really uncertain about whether this profession was for me or whether I could do it,” Cohen said. “I kind of continually felt like I was being seen as a joke that first year.”

He said speaking with students who had an interest in his class and professors who were going through similar struggles was “fortifying.”

“Even just in our day-to-day lives, we have a little superpower to help other people feel like they belong through just sharing vulnerabilities and sharing stories,” Cohen said.

For example, in one of the experiments mentioned in “A Question of Belonging: Race, Social Fit, and Achievement,” Cohen and Walton found that nearly all first-year Black college students assessed in the study benefited from learning that hardship and doubt were common to all first-year students regardless of race. It reduced the racial achievement gap in classroom performance, improving Black students’ sense of fit on campus and boosting their belief in their potential to succeed.

Transmitting wisdom to future generations and allowing younger students to see role models like them succeed is also important, he said.

Another intervention he suggests is value affirmations, structured writing assignments in which people write for a few minutes about their most important values. The practice helps people ground themselves and remind them of their authentic selves.

Additionally, he said so-called subtractive interventions, where harmful stereotypes are removed, may also help. For instance, sending the message that there are certain people who have what it takes to succeed and others who don’t further fuels the sense of belonging uncertainty. Deemphasizing this culture could help mitigate duck syndrome.

Similarly, using social media less may also ease the problem. Cohen said that social media has created a norm in which individuals are constantly in a “performative mood” and become “obsessed with getting likes,” making them focused on social validation over self-worth.

For example, “The Welfare Effects of Social Media,” a paper by well-known economists Hunt Allcott, Luca Braghieri, Sarah Eichmeyer and Matthew Gentzkow published in the American Economic Review, found that deactivating Facebook caused significant improvement in self-reported happiness, life satisfaction, depression and anxiety — an effect around 25 to 40% of the effect attributed to participating in therapy.

“One of the most important things for our own health is some kind of unconditional self-regard, a kind of belief or faith in ourselves that transcends what other people think,” Cohen said.

To learn more about these issues, check out Cohen’s book “Belonging: The Science of Creating Connection and Bridging Divides.”