Students who walked into new history teacher Holly Royaltey’s World History and AP Gov/Econ classes in August received a surprise when handed their syllabus.

Rather than grading on a typical scale — where tests and homework have different weightings — they learned that Royaltey uses emoticons ranging from a red button indicating an assignment is in trouble to a fire emoji, symbolizing “above and beyond.”

A check mark is considered the baseline, and directly tests the knowledge acquired in a lesson. On the contrary, a fire emoji next to an assignment means it relates to questions that apply the concepts of the lesson, and usually ties back to an Essential Question defined at the beginning of each unit. To achieve the fire level, students must use critical thinking and analysis, two skills the classes emphasize.

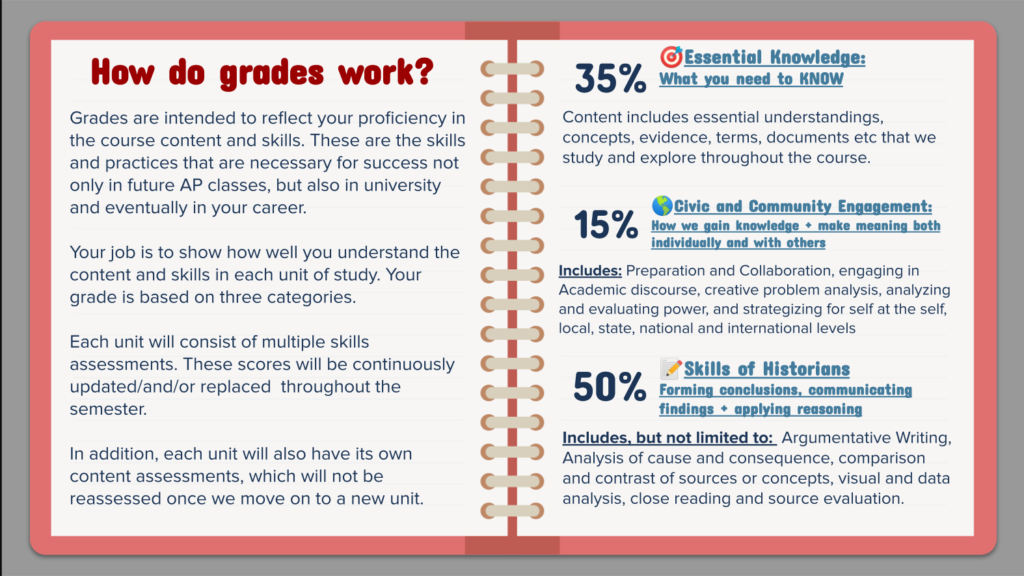

Royaltey’s system also differs from the traditional grade weighting system, where most history classes count tests as 40% of the overall grade and homework as 10%-20%. Instead, she has created three categories with different weightings: skills of historians, content, and community and civic engagement. Skills of historians — which includes image analysis and close reading — is weighted at 50% of the grade, since it focuses on assessment techniques which are applicable in different courses and disciplines.

An assignment that consists of close reading and follow-up questions would be under Skills of Historians. It could feature simpler questions at the beginning, whether taking notes or answering directly from the text. Those questions would be “OK,” since they are baseline comprehension. A question that requires the combination of various sources and assignments would be a check mark, since it requires more thinking and connection. A fire question could relate the effects of the event, reasons behind it, and its relation to an Essential Question.

“I attended a conference in 2008 titled ‘Equity in Grading,’ which was about how a student’s gradebook is reflective of their actual learning and comprehension,” Royaltey, who previously taught at Del Mar High School, said. “I got tired of points, and I no longer wanted students to strive toward making a certain percentage.”

Hoping to increase focus and reduce grade fluctuations, Royaltey has only a few assignments listed in the Canvas gradebook, and she continues to update those few grades as assignments of the same category are completed. This means a grade received on as few as three assignments can be the only scores reflected in a student’s overall grade, a more accurate representation of their comprehension at that point in time.

“Rather than students starting out with super high grades and then slacking the rest of the semester, a replacement system may start their grade out slower, but gives value to the fact that it takes time to learn and adapt,” she said.

Students found the system strange at first due to confusion regarding how certain assignments were graded.

“The low point values also make it hard to do well on an individual assignment, since losing one point drops the grade 20%,” senior Economics/AP U.S. Government student Ara Esfarjani said.

Despite some confusion from students at the start, Royaltey has found that grades are often at their highest by the end of the semester, and most students do even better in second semester when they’re used to the system. This, combined with the learning benefits, has encouraged her to maintain her grading system for the past 15 years.

“Switching to this changed the conversation I was having with my students,” Royaltey said. “I’ve seen a shift in their approach to learning, and the productivity levels during class are much higher.”